How photography (and the iPhone) changed our holidays

The iPhone 11 has been revealed. Its biggest selling point? For many, it will be the suped-up camera. The triple lens technology offers another upgrade to our holiday snaps – and will boost our mistaken sense that we’re professional-level travel photographers.

Since the Instagram app launched in 2010, our phone has been a tool for documenting – and showing off – our travels. Smartphone marketing reflects this. Adverts for Google’s Pixel phones emphasise the high quality photographs they take and the unlimited photo storage. Meanwhile, Samsung, like Apple, added a “triple lense” camera to its latest phone.

Over 100 million photos are uploaded to Instagram each day. At the time of writing there were more than 440 million tagged #travel. Research shows that more than half of 18-65 year-olds book trips based purely on pictures they’ve seen on Instagram.

The destinations coping with overtourism must partly blame travellers’ obsession with capturing their own version of the quintessential Insta-snaps, such as gazing out over the sheer drop from Norway's Trolltunga rock formation or perched among the white cliffs and blue domes of Santorini.

Millennials, the first generation to embrace Instagram, will likely have had their first taste of holiday photography using a disposable camera.

With these cheap, handy gadgets you had just 27 clicks to capture your summer – it was point, shoot and hope for the best. There was no delete button, so you had to saviour each snap. And yet, somehow, a large number of the final prints would be part concealed by a thumb. Often when the ideal ‘Kodak moment’ arose, you’d have forgotten the camera altogether.

But the holiday snaps we salvaged from our amateurish attempts are still lying around, with plenty of opportunity to reminisce. They’re a physical entity, unlike the hundreds of thousands of pixels on our smartphones. Lose your phone, see your account hacked or forget to back them up and they are gone. Capturing them can also be a big distraction from holiday enjoyment.

Travel with a snap happy friend or partner and they’re forever trailing behind adding to their holiday album. Or maybe you're the photo-obsessive. According to one study, British travellers spend an average of two hours and 50 minutes taking photos on holiday.

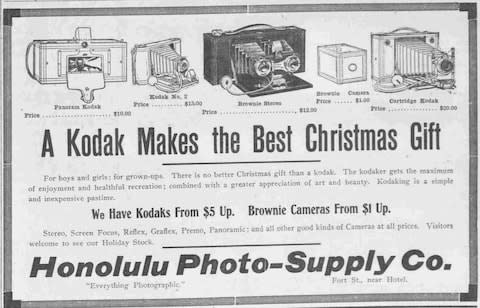

And so maybe we should mourn the single-use camera (now usually reserved as a wedding favour). As restrictive as it was, it left us to immerse ourselves in relaxing or exploring. It came to the market in 1986 and ruled our photographic ambitions well into the 1990s. In 1993, Kodak finally put the already well-worn phrase the “Kodak moment” into a campaign.

It had taken over 100 years for Kodak to market the phrase. Its first consumer-ready product was the Kodak Eastman, which launched in 1888. It sold for $25, the equivalent of around $675 (£545) in today’s money.

By then, tourists were already used to the holiday photo – the market was quick to capitalise on the technology. The daguerreotype process, introduced in 1839, got things started. Dr Michael Pritchard, a photohistorian at the Royal Photographic Society and author of my book A History of Photography in 50 Cameras says of the daguerreotype: “It was the first commercially successful photographic process, giving the public an accessible and affordable way of accurately recording their likeness.”

Families and individuals looking for someone to record a moment would previously have gone to portrait painters or miniature painters, but photographs were much more affordable – and therefore accessible.

In France, the invention brought with it dauerreotypomaia – a craze for photography not unlike our modern-day selfie obsession. Subjects would have to sit for 20 seconds to get the perfect shot.

A cartoon from 1839, titled La Daguerreotypomanieshows how the mass availability of photography transformed people’s lives in Paris. Long queues of budding subjects snake around waiting for entrepreneurial photographers to take their snap.

Over in Britain, the first photographic studio opened in London in March 1841. While this process was mostly done in a studio, travellers began documenting what they saw using daguerreotype, says Pritchard. A collection of daguerreotype photographs taken in the 1850s by nineteenth century art critic John Ruskin were auctioned in 2015. They show how he used photography to document trips to Italy, France and Switzerland. He even captured Venice long before its overtourism problems.

Holiday photos really went mainstream with the collodian process, which was introduced in 1851. It produced an image on glass, called an ambrotype, or on metal, called a tintype. Pritchard explains that it was easy and relatively quick to produce an instant portrait using this process. Photographers headed for British seasides to turn “while you wait” photographs into souvenirs for day-trippers.

These entrepreneurs set up along the shore and snapped their clients in typical beach poses: on a donkey, or with the tide rising behind.

Tintype photographs were used from the 1870s to the 1950s, when they were still being made at beaches and fairs. Often they were turned into ‘real photo postcards’. Many were taken in studios decorated with backdrops painted like sea and filled with sand – today we mimic this artificiality with our Instagram travel snaps.

Another approach created more candid snaps. An evolution of the entrepreneurial beach photographer was a group called ‘walkies’. They captured their subjects unawares, then handed them a number that they could use to collect a print of the photograph. It was a competitive field. Before the single-use camera, the most democratising invention was, according to Pritchard, the brownie. “With the introduction of the Brownie camera in 1900 and better films, which were more forgiving over exposure errors, holiday photography became much more informal and relaxed and moved out of the studio on to beaches as ordinary people photographed themselves, their family and places in the way they wanted."

Fast-forward to the eighties and quick to develop disposable camera snaps saw us regaling friends and family with albums we printed at Boots, then we moved onto affordable digital cameras, and bombarded our Facebook friends with our summer travels. Within a few years Instagram would become ubiquitous. The latter owes much to both the Instamatic and the Polaroid, which debuted in 1948.

So, what for the future of our holiday photos? Maybe the era of the travel influencer will peter out, or evolve. Perhaps we’ll become more responsible and no longer base our travels solely on the photographs we can collect. But over 130 years of holiday pictures suggest our travels may become ever more dominated by the photos we take.

Inspiration for your inbox

Sign up to Telegraph Travel's new weekly newsletter for the latest features, advice, competitions, exclusive deals and comment.

You can also follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.