Children from the poorest parts of England are more than twice as likely to be obese

Words by Alexandra Thompson.

Children from the most deprived parts of England are more than twice as likely to be obese as those from privileged backgrounds, research suggests.

A report published by Unicef today looked at the BMI of youngsters from 41 countries around the world. Researchers found the UK has the 14th biggest childhood obesity problem, with nearly a third (31%) of five-to-19-year-olds being overweight in 2016.

In England, specifically, one in three children leave primary school overweight, with deprived areas being the worst hit, the report showed.

The study’s authors call these poor regions “fast-food hotspots”, with five times more pizza, fried chicken and burger outlets than the most well-off parts of the country.

The report did not look at Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland, however, statistics suggests they have similar problems with childhood obesity.

Writing in the report The State of the World’s Children, the authors said: “Children’s diets are heavily influenced by the environments in which they live.

“England’s poorest areas are fast-food hotspots, with five times more outlets than in the most affluent areas.

READ MORE: Obesity isn't a choice – nor is it 'down to a lack of willpower'

“Children from poorer areas are disproportionately exposed to takeaways selling fried chicken, burgers and pizzas, and poorer areas also have more visible advertising for unhealthy foods than wealthier areas.”

The UK government has pledged to halve childhood obesity by 2030. To achieve this goal, a tax on sugary drinks has already been introduced. There is also talks of banning unhealthy snacks at supermarket check outs and ending unlimited refills on sodas.

While obesity is a major concern, the report also found nearly two million children in England are malnourished, with just a fifth of five-to-15 year olds getting their five-a-day.

Even in well-off cities like London, almost one in 10 youngsters are said to go to bed hungry.

Aside from England, the report did not look at specific countries in the UK. In 2017, NHS Scotland published statistics showing 13% of children in the poorest areas start school obese, compared to 7% in the wealthiest regions.

Public Health Wales released a report in 2016-17 showing 12.4% of four and five-year-olds were obese.

The situation is similarly dire in Northern Ireland, with a quarter of youngsters carrying too much weight, according to its Department of Health.

READ MORE: How much sugar is in your favourite 'healthy' drink?

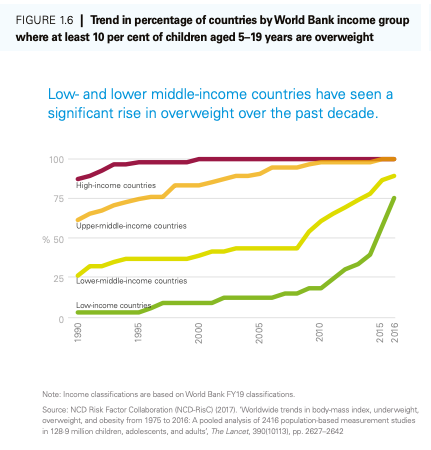

Out of the 41 countries analysed, the US came out on top, with 41% of its five-to-19 years olds being overweight in 2016, a 49% increase since 1990.

The UK was not far behind, with its obesity problem rising by 33% over the 26 years.

Other high-income countries also featured, with New Zealand, Italy, Australia and Spain all making the top 10.

On the other end of the scale, Japan was found to be the least affected, with just 14% of its youngsters being overweight in 2016. However, this was still a 14% rise since 1990.

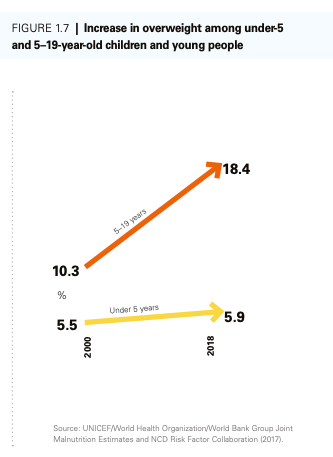

Overall, one in three (200 million) under five-year-olds around the world is either under or overweight.

The report’s authors warn a lack of nutrition in early life could put youngsters at risk of poor brain development, as well as slow learning, weak immunity and even death.

It also found 400 million children worldwide are overweight or obese. Research has consistently linked obesity in childhood to an increased risk of the condition in later life, putting people at risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers.

READ MORE: Doctor slated for saying people are 'programmed to be fat', but do obesity genes really exist?

Poor eating habits are said to begin as early as six months old, when babies are typically weaned onto solid food, the report found.

By the time infants become teenagers, 42% of those in low or middle-income countries have at least one soda a day. In high-income nations, 62 per cent of adolescents drink a soda every day.

“Despite all the technological, cultural and social advances of the last few decades, we have lost sight of this most basic fact: If children eat poorly, they live poorly,” said Henrietta Fore, UNICEF’s executive director, said.

“Millions of children subsist on an unhealthy diet because they simply do not have a better choice.

“The way we understand and respond to malnutrition needs to change: It is not just about getting children enough to eat; it is above all about getting them the right food to eat. That is our common challenge today.”

Unicef is calling on governments to educate people on nutrition and introduce more taxes that make unhealthy food less accessible.

“We are losing ground in the fight for healthy diets,” Ms Fore said.

“This is not a battle we can win on our own. We need governments, the private sector and civil society to prioritize child nutrition and work together to address the causes of unhealthy eating in all its forms.”