Coronavirus: is it safe to go to the supermarket?

With Britons being told to stay indoors as much as possible amid the coronavirus outbreak, many may be wondering whether a trip to the supermarket is safe.

Boris Johnson enforced draconian measures on Monday evening, stressing people are only to venture out for “very limited purposes”, including “shopping for basic necessities as infrequently as possible”.

The prime minister urged the public to take advantage of food delivery services, however, this may be easier said than done.

Ocado is placing customers in a long queue to do an online shop, while Tesco has no delivery slots available until at least mid-April in certain areas.

With many forced to head to the shops for food, are supermarkets hotspots for the coronavirus?

The new coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, at the end of last year.

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 441,100 cases have been confirmed worldwide, of whom over 111,900 have “recovered” to date, according to John Hopkins University.

Globally, the death toll has exceeded 19,700.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

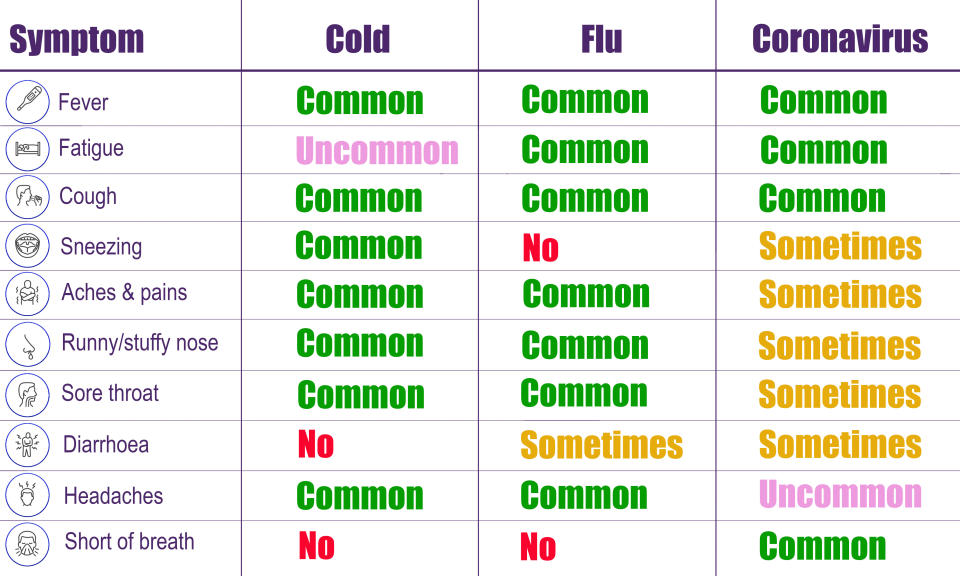

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

Cases have been plateauing in China since the end of February, with Europe now the epicentre of the pandemic.

The UK has had more than 8,300 confirmed cases and 440 deaths.

Coronavirus: are supermarkets a hotspot for infection?

Supermarkets, and any confined space with lots of people, could leave shoppers vulnerable to infection.

The government has urged anyone with the coronavirus’ tell-tale fever or cough to self-isolate entirely for seven days, not even venturing out to buy food.

Every member of their household has been told to do the same for 14 days.

The situation becomes more complex when you remember not all patients are thought to develop symptoms, an issue which has been hotly debated.

On 3 March, the World Health Organization’s director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “Evidence from China is only 1% of reported cases do not have symptoms.”

Scientists from The University of Hong Kong scientists later claimed 12.1% of patients are not thought to develop a fever.

Dr James Gill, of the Warwick Medical School, said: “Let's assume asymptomatic patients are also spreaders.”

“If you go to the shops for a few items and encounter 30 people, which is reasonable in a big supermarket, you could potentially be exposed to people infected with the virus who are not showing signs.”

The coronavirus mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets that have been coughed or sneezed out.

Asymptomatic patients may not be coughing or sneezing, which could mean they pass the infection on less readily.

As well as being airborne, research suggests the coronavirus can survive for up to three days on plastic and stainless steel.

People may “pick up” the virus and then touch their eyes, nose or mouth, unwittingly infecting themselves.

Consumers can ‘unwittingly’ infect themselves with coronavirus

Prof Sally Bloomfield, from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said that any virus contamination would “come from someone who has contaminated hands”.

“Although hands and hand-contact surfaces are thought to be a major contributor to spread, the main risk comes from ‘hand-contact surfaces recently and frequently touched by many other people’.

“If you think about it, the supermarket provides an ideal setting for this to occur – many people touching and replacing items, checkout belts, cash cards, car park ticket machine buttons, ATM payment buttons, paper receipts – not to mention being in the proximity of several other people”.

In an ideal scenario, all food would be dropped off at our front door.

Dr Gill said: “Food delivered to the home can be done via ‘no contact drops’, reducing direct exposure to whoever is dropping off the food.”

This can include asking the delivery driver to leave the shopping on the doorstep, rather than handing it over.

Theoretically, the virus could survive on packaging if bagged by contaminated hands.

“Initially the longevity of the virus may cause concern over home deliveries, until we remember that wiping over surfaces with simple dilute household bleach will inactivate the virus within one minute,” said Dr Gill.

“Food deliveries will carry a lower risk of exposure than going to the supermarket, and most people have bleach and a cloth to be able to wipe over those home deliveries, effectively eliminating risk”.

Although Prof Bloomfield stressed the likelihood of delivery shopping carrying the coronavirus is low.

“The items have probably been touched by relatively few people”, she said.

Likelihood of coronavirus on delivery shopping ‘low’

“If you want to take further precautions then place all the items in cupboards, fridge etc, where any residual viral infectivity will further decrease before you handle it again, and then wash your hands thoroughly.

“Remember there is no such thing as zero risk”.

For those unable to secure a home delivery slot, remember regular hand washing and social distancing are the most effective ways to ward off infection.

Yahoo UK previously reported on the risk of picking up colds and flu at the supermarket, with these pathogens thought to transmit in the same way as the coronavirus.

“People often load the shopping in the car, get home hungry and open a bag of crisps, not realising their hands are dirty,” said Dr Lisa Ackerley, chartered environmental health practitioner and spokesperson for Jakemans.

Being in the comfort of our own vehicle may also encourage complacency.

“When we’re in a car, we’re in our own bubble and may rub our eyes as we drive along,” added Dr Ackerley.

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus is one of seven strains of a class of viruses that are known to infect humans.

Others include the common cold and severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

Early research suggests four out of five cases are mild.

In severe incidences, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients’ immune systems fighting off the virus naturally.

In severe cases, hospitalisation may be required if a patient needs “supportive care”.

This may include ventilation while their immune system gets to work.

While coughs and sneezes are the main routes of infection, there is also evidence the coronavirus may be transmitted in faeces and urine.