Coronavirus: Evidence children continue to mix after schools close

Children may still be mixing despite schools shutting amid the coronavirus outbreak, research suggests.

Schools, colleges and nurseries in the UK shut their doors indefinitely after the final bell on 20 March.

With the coronavirus strain virtually unheard of at the start of the year, no one has immunity to the infection.

Early research suggests the virus is mild in four out of five cases, however, it can trigger a respiratory disease called COVID-19.

The vast majority of deaths worldwide have occurred in the elderly or already ill, however, children can readily pass the infection to the vulnerable.

To better understand the effectiveness of shutting schools, scientists from King’s College London looked at whether children continued to mix during previous infectious outbreaks around the world.

All 19 studies suggested the youngsters still left their home or were cared for by people they did not live with.

With school closures set to last longer than the standard two-week limit, experts worry the picture could be worse for the coronavirus. Reports of the seriousness of the pandemic, however, may encourage parents to comply.

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan at the end of last year.

It has since spread into 180 countries across every inhabited continent.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 962,900 cases have been confirmed, of whom over 202,900 have “recovered”, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Incidences have been plateauing in China since the end of February, and the US and Europe are now the worst-hit areas.

The UK has had more than 34,100 confirmed cases and 2,921 deaths.

Globally, the death toll has exceeded 49,100.

Coronavirus: Closing schools ‘slows transmission’

Boris Johnson has enforced draconian measures that only allow Britons to leave their home for “very limited purposes”, like shopping for essentials.

Anyone with the tell-tale fever or cough has been told to self-isolate entirely for seven days, while other members of their household must do so for two weeks.

Johnson’s decision to close schools was praised by experts.

Schools are confined spaces where children with “less-than-perfect hygiene behaviours” mix, the King’s scientists wrote in the journal Eurosurveillance.

Past research suggests youngsters come into contact with fewer people on the weekends or holidays, with infection rates also falling among children during school breaks or teacher strikes.

Many experts worried, however, elderly grandparents may be called upon to provide childcare while adults set up office at home.

NHS staff and other key workers are permitted to send their children to school during the lockdown. Industries that can work from home have been told to do so.

Speaking at the time closures were announced, Dr Charlotte Jackson from University College London said: “Closing schools aims to reduce contact between children, reducing the risk of them being infected and also of them passing the infection on to people in other age groups.

“The idea is this will slow down transmission, so the outbreak takes longer and has a lower peak.

“There are also operational considerations. It is difficult to keep schools open if many teachers are unable to come to work or if children are ill or kept home by concerned parents.”

Coronavirus: Benefits of school closures ‘attenuated’ if children still mix

The 19 studies all analysed a quarantine period of no more than 14 days, which is soon to be exceeded by the ongoing coronavirus lockdown.

While social activities reduced, all the studies reported the children leaving their home or being cared for by people outside of their household, like a nanny or family friend.

The prime minister has stressed Britons are to avoid social contact with anyone outside their home.

Three of the studies noted teenagers aged between 16 and 18 were more likely to mix, particularly later on in the week.

Children aged 12 and over were found to be more likely to interact at parties than their younger counterparts.

A Japanese study even found youngsters were more likely to leave the house during an enforced school closure.

Children whose parents found the closure inappropriate were also more likely to take part in out-of-home activities.

Overall, the youngsters stayed at home for more than 94% of the days they were advised to do so.

“During a major infectious disease outbreak, school closure has the potential to slow the spread of infection,” wrote the King’s scientists.

“However, the effects of a closure will be attenuated if children continue to mix.”

The scientists and other experts have stressed parents should be made aware of the importance of school closures to ensure the intervention’s success.

“Convincing parents of the purpose and necessity of school closures is the most important step, as parents’ attitudes filter down to their children”, said Dr Angharad Rudkin from The University of Southampton.

“To convince parents, information needs to be clearly communicated, the messages need to be relevant with clear examples of what is required and why, and any expectations of behaviour change needs to be backed up by support around financial, social and emotional difficulties.”

Coronavirus ‘different to previous outbreaks’

Experts have largely welcomed the “reliable review”.

One noted the studies only analysed lockdown periods of two weeks, with longer quarantines being unprecedented.

“The studies were not set in the context of the particular recommendations of the current time”, said Professor Sarah Stewart-Brown from the University of Warwick.

“So the data are not directly applicable.

“Hopefully after the Easter holidays when we get access to antibody testing we will start to see reliable information about the spread of the virus in the UK population in this pandemic”.

Dr Jackson called the research a “useful starting point”, but stressed the coronavirus is an unprecedented pandemic that can only be somewhat compared to the studies included.

“The situation with COVID-19 is different to previous infectious disease outbreaks,” she said.

“Schools are being closed for longer periods, the disease has a higher case fatality ratio than [for example] influenza and the importance of social distancing is being publicised extensively.

“As the authors note, all of these may influence the extent to which children stay at home.”

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus is one of seven strains of a virus class that are known to infect humans.

Others include the common cold and severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

The coronavirus mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets expelled in a cough and sneeze.

There is also evidence it can be transmitted in faeces and urine and survive on surfaces.

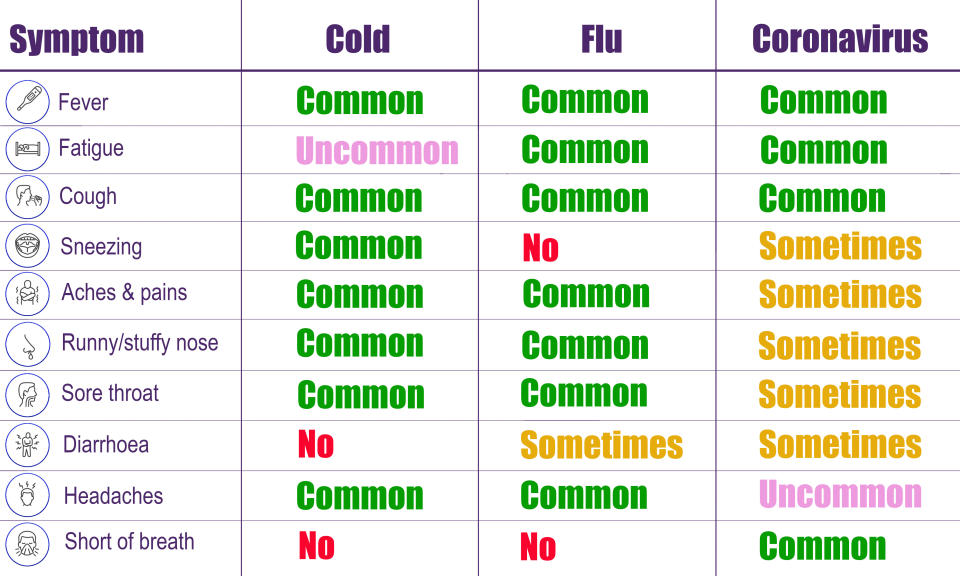

Symptoms tend to be flu-like, including fever, cough and slight breathlessness.

In severe incidences, pneumonia may come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the infection by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.