Why may the COVID-19 coronavirus become seasonal when Sars was a one-time outbreak?

Concerns have been raised the coronavirus pandemic may become a seasonal infection.

Virtually unheard of at the start of the year, the strain is triggering life-threatening disease – called COVID-19 – in a relatively small number of patients.

With the global death toll exceeding 15,400, countries throughout Europe have been put on “lockdown”.

While one model suggests this could help save thousands of lives, experts worry the coronavirus may re-emerge next winter, similar to seasonal flu.

This has left some wondering why the circulating coronavirus may become an annual issue, while fellow strain severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) has had no reported cases since 2004.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan at the end of 2019.

It has since spread into more than 160 countries across every inhabited continent.

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 353,600 cases have been confirmed worldwide, of whom over 100,400 have “recovered”, according to John Hopkins University.

Cases have been plateauing in China since the end of February, with Europe now the epicentre of the pandemic.

The UK has had more than 5,900 confirmed cases, of whom 335 have died.

Why may the coronavirus become a seasonal infection?

On Saturday, Boris Johnson told the UK’s 1.5 million vulnerable residents – including severe asthmatics and blood-cancer patients – to self-isolate entirely for the next three months.

Even healthy Britons have been told to avoid social contact, ditch non-essential travel and work from home, if they can.

Although the vast majority of deaths worldwide are occurring among the elderly and already ill, breaking the “chain of transmission” is hoped to reduce fatalities and ease pressure on a strained NHS.

The government’s approach was largely based on a model put together by Imperial College London scientists.

The team concluded “suppressing” the outbreak, “reducing case numbers to low levels and maintaining that situation indefinitely”, would likely be more effective than “mitigating” it.

Mitigation focuses on “slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread” by protecting the vulnerable.

While reducing virus exposure will inevitably cause case numbers and deaths to decline, some have argued it fails to allow the public to build up herd immunity.

The outbreak may therefore return as powerful as ever once these extreme measures are lifted or if the infection becomes seasonal.

It appears to be a race against time to develop a vaccine before the outbreak re-emerges.

The coronavirus mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets coughed or sneezed out by a patient.

“Droplets spread infections more in winter in the northern hemisphere,” Professor Paul Hunter from the University of East Anglia previously said.

“The number of cases may reduce in summer and re-emerge in winter.”

Viral infections like colds and flu tend to be more common in the northern hemisphere’s winter.

Although unclear, the norovirus (winter vomiting bug) appears to be more readily broken down when exposed to high levels of UV light.

Cold temperatures may also drive people to huddle indoors, facilitating the spread of infections.

“[Viruses] tend to be more common in winter, which may be because of schools opening and closing,” Professor John Edmunds from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine previously added.

It is worth noting, however, the coronavirus has been reported in warm climates.

Australia has had more than 1,600 confirmed cases despite it being summer in the southern hemisphere.

How similar is the coronavirus to Sars?

The coronavirus is one of seven strains of a virus class that are known to infect humans.

Of the other strains, four cause the common cold, one leads to Sars and the final strain triggers Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers).

Sars killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak, while Mers’ 2012 outbreak lead to 858 deaths, with a handful of cases still arising every year.

The new coronavirus is said to be more genetically similar to Sars than any other strain of that class.

At the beginning of February, scientists from Fudan University in Shanghai found the new strain appears to be 89.1% genetically similar to “a group of Sars-like coronaviruses”.

While seven strains are known to infect humans, others just cause ill health in animals.

A team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Wuhan also analysed the viral DNA of five coronavirus patients.

They found the new strain seems to share 79.5% of its genetics with Sars and is 96% “identical” to a coronavirus that infects bats.

Speaking at the time, Professor Ian Jones from the University of Reading, said: “[The new coronavirus] is a bat virus and Sars is the closest relative seen previously in people.

“In essence, it’s a version of Sars that spreads more easily but causes less damage.”

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses “determined it is the same species as Sars but a different strain of the species”, said Dr Nathalie MacDermott from King’s College London.

Why may the coronavirus become seasonal when Sars never did?

Chinese authorities were famously tight-lipped about Sars, not informing the World Health Organization until 305 cases - and five deaths - had occurred across six districts in the province Guangdong.

The outbreak was controlled, however, in eight months.

With the ongoing pandemic, the authorities have been praised for being transparent early on.

Just over three months in, however, more than 15,400 deaths have been reported.

“Because [the coronavirus] has affected many more people, it is expected to continue to circulate, possibly in a seasonal way,” Dr Tom Wingfield from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine told Yahoo UK.

The new coronavirus is known to be infectious before symptoms develop, with most patients showing the tell-tale fever and cough within five days.

“Sars couldn’t become seasonal because it’s transmission only really after symptoms became apparent meant we were able to contain and eradicate it,” Dr Michael Skinner from Imperial College London told Yahoo UK.

“If it’s not out there, it can’t be seasonal.

“With [the new coronavirus], there’s little confidence we’ll be able to put it back into a stoppered bottle (like Sars) until we have a vaccine”.

Dr Skinner added a “necessary proportion of the population” need to have the jab to create herd immunity.

Over time, people my have “forgotten the problems [the coronavirus] caused”.

Both Sars and the new coronavirus invade human cells via the entry receptor ACE2.

The new coronavirus is “far more efficient at binding” to the receptor than Sars, according to Professor Martin Hibberd from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

“As a highly-transmissible virus, many scientists are expecting it to cause seasonal disease in the same way as other highly-transmissible viruses, such as influenza or other coronaviruses that cause the common cold,” he told Yahoo UK.

What is the coronavirus?

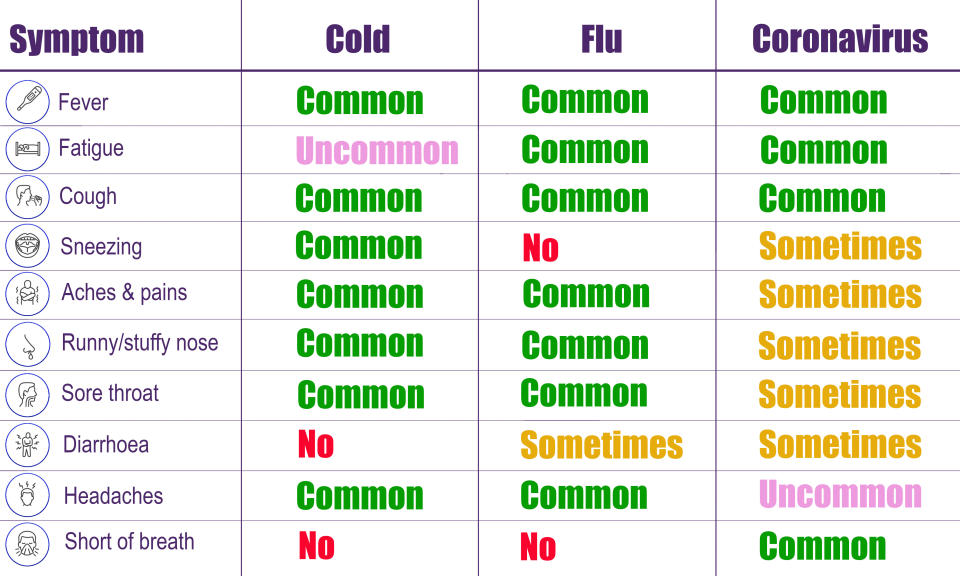

The coronavirus tends to cause flu-like symptoms initially, such as a fever, cough or slight breathlessness.

While it mainly spreads via coughs and sneezes, there is also evidence it may be transmitted in faeces and urine.

Early research suggests four out of five cases are mild, with patients not requiring any hospital care and their immune system naturally fighting the virus off.

In severe cases, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, where gas exchange takes place.

This can cause oxygen levels to fall to dangerously low levels in the bloodstream, while carbon dioxide accumulates.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment.

Those requiring hospitalisation are given “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the infection by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.