Coronavirus: what is the difference between an antigen and antibody test?

With the coronavirus making headlines all over the world, officials have stressed the importance of both antigen and antibody tests in getting a handle on the pandemic.

Virtually unheard of just three months ago, the new strain has infected more than 474,200 confirmed patients worldwide, with the death toll exceeding 21,500.

Boris Johnson claimed antibody tests have the potential to be a “total game changer”, while health secretary Matt Hancock reassured 3.5 million devices are on their way to the NHS.

When it comes to antigen tests, scientists from The University of Hong Kong claimed there is an “urgent need” for the kits to be rolled out.

With “antigen” and “antibody” sounding like medical jargon, many may be wondering how the tests differ and why both are important.

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, at the end of last year.

Early research suggests four out of five cases are mild, with more than 115,000 patients now “recovered”, according to John Hopkins University.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

Cases have been curbing in China since the end of February, with Europe now the epicentre of the pandemic.

Italy alone has had more than 74,300 confirmed cases and over 7,000 deaths.

In the UK, more than 9,600 patients have been reported, of whom 465 have died.

Coronavirus: what is an antigen test?

Antigen tests detect the presence or absence of, unsurprisingly, an antigen.

These are substances, usually proteins, on the surface of an invading pathogen – like viruses, bacteria and fungi.

The immune system recognises an antigen and launches a response.

Testing for a coronavirus-specific antigen tells an individual whether they are carrying the infection.

At present, all Britons have been told to stay indoors, venturing out for “very limited purposes”, including “shopping for basic necessities as infrequently as possible”.

Anyone who develops the coronavirus’ tell-tale cough or fever must self-isolate entirely for seven days, not even leaving the house to buy food or other “essentials”.

Every member of their household must do the same for 14 days.

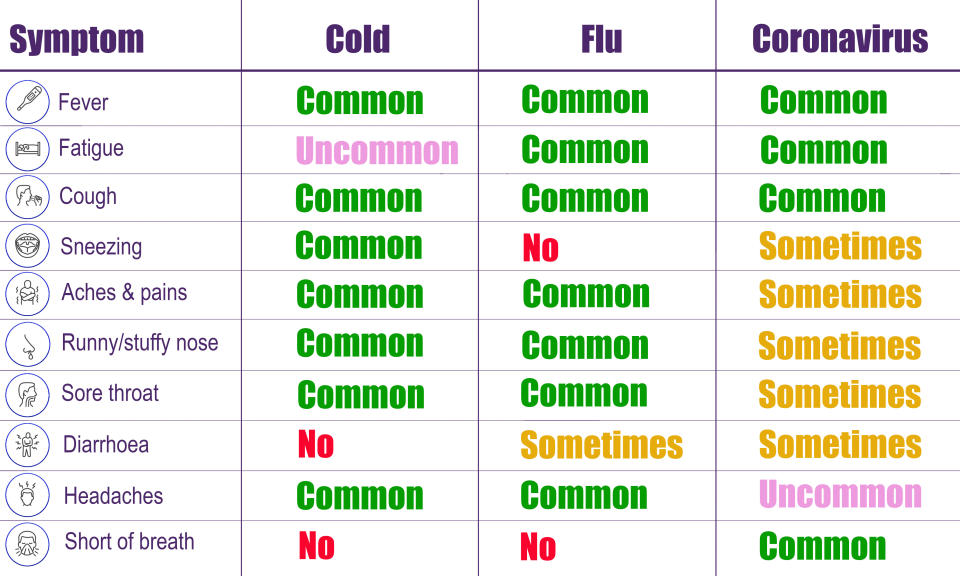

With the coronavirus overlapping with the northern hemisphere’s cold and flu season, many may be self-isolating when all they have is the seasonal sniffles.

Antigen tests allow people to be sure they are carrying the coronavirus, enabling them to take the necessary social distancing precautions.

At the start of the outbreak, Britons returning from high-risk countries like China and Italy were offered an antigen test.

With strict travel restrictions now in place, only hospital patients are routinely being tested in the UK.

This is usually via a nasal or throat swab, or testing phlegm if the patient is coughing it up. Blood may also be drawn and tested.

Coronavirus: what is an antibody test?

Antibody tests tell an individual whether they have already fought off the coronavirus.

While no one can say for sure how long immunity lasts, it is expected for “at least the intermediate term”.

People who have overcome the coronavirus are unlikely to become reinfected and pass the pathogen on, allowing them to go back to their normal routine.

When the immune system encounters a new virus, it releases proteins called antibodies.

With every new infection, the antibody produced is unique, responding to an antigen on the virus in question.

When a virus is identified, it can take time for the immune system to make a “blueprint” of the antibody needed and produce sufficient numbers to kill off the infection.

Once the infection has passed, a new type of antibody is produced that “remembers” the blueprint and maintains a small supply of the virus-fighting proteins.

If the body is exposed to the same virus again, the immune system responds much more quickly, releasing these “memory antibodies”.

This is the basis on which vaccines work, by exposing the body to a “mild amount of disease” so it can respond more readily if the real thing comes along.

An antibody test would reveal if an individual has these “memory” proteins in their bloodstream, indicating they have immunity.

“These people will not need to re-isolate themselves when they get another respiratory infection”, Professor Keith Neal from the University of Nottingham previously said.

Although unclear, the test may involve mixing a sample of a person’s blood with the coronavirus antigen, looking for a reaction.

Boris Johnson likened it to an at-home pregnancy test, using blood rather than urine.

NHS workers will be given an antibody test as a priority, said Professor Chris Whitty, the UK’s chief medical adviser.

Health-service staff are more likely to be exposed to the coronavirus and must self-isolate like everyone else if they develop symptoms.

With the NHS under strain, workers are needed more than ever.

Once antibody tests have been sufficiently scaled up, they can be rolled out to the general public.

“This will help society normalise little-by-little, even while we have a high number of cases,” Professor Whitty previously said.

Antibody tests will also indicate the number of patients who do not develop symptoms.

Those without symptoms are not obligated to stay indoors entirely, but may still be infectious.

The proportion of these patients has been debated.

On 3 March, the World Health Organization’s director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said: “Evidence from China is only 1% of reported cases do not have symptoms”.

The Hong Kong scientists claimed, however, 12.1% of patients do not develop a fever.

Coronavirus: why are tests taking so long?

Dr Adhanom Ghebreyesus said he had a “simple message”: “Test, test, test.

“We cannot stop this pandemic if we do not know who is infected.”

More than 90,000 tests have already been carried out in the UK, with officials looking to increase this to 25,000 tests a day within four weeks.

Before at-home tests can be rolled out, however, officials must be sure of their accuracy.

When it comes to “memory” antibodies, different people have varying concentrations of the proteins in their bloodstream.

The test must be sharp enough to detect even low levels.

“The only thing worse than no test is a bad test,” said Professor Whitty.

Speaking of the importance of accuracy, Professor Patrick Vallance – the UK’s chief scientific adviser – added: “If it means a delay to get there, that delay is worth having.

“Telling someone they don’t have it when they do or telling someone they’re immune and they’re not, that is not a good position to be in”.

The other obstacle is the demand outstripping supply.

The coronavirus has been identified in 175 countries across every inhabited continent.

“[There are] shortages along supply chains as many countries in the world simultaneously want this new thing,” said Professor Whitty.

“That’s the practical reality.

“[This is not] something we will suddenly be ordering on the internet next week, we need to go about it in a systematic way”.

Dr Alexander Edwards from the University of Reading previously said: “It is absolutely possible to make very large numbers of these rapid antibody tests because the factories needed to make such diagnostic tests can scale up production rapidly, using very sophisticated ‘printers’ onto rolls of special paper.

“The limiting factor is time – firstly to make viral targets and secondly to fully test them with real patient samples to be sure they give accurate data.

“The quickest tests may not be the most accurate, but the most skilled experts will be 100% focussed on making high quality tests.

“We must allow our experts to check accuracy before we can use these”.

Once available, Professor Sharon Peacock from Public Health England claimed people may be able to order an antibody test off Amazon.

“People will be able to order a test or go to Boots to have their finger-prick test done,” she said.

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus is a strain of a class of viruses, with seven known to infect humans.

Others include the common cold and severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

The coronavirus mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets coughed or sneezed out by a patient.

There is also evidence it can be transmitted in faeces and urine and survive on surfaces.

While most cases are mild, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the infection by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.