'Peeping Tom' at 60: How the British 'Psycho' killed a beloved director's career

This week marks the 60th birthday of one of the most controversial British horror movies ever made — Michael Powell’s powerful Peeping Tom. Derided by critics on its release in 1960, the film is now widely considered to be a masterpiece and a milestone in the horror genre, particularly on this side of the Atlantic. That reappraisal came too late for Powell, though, and didn’t stop the movie proving disastrous for his career.

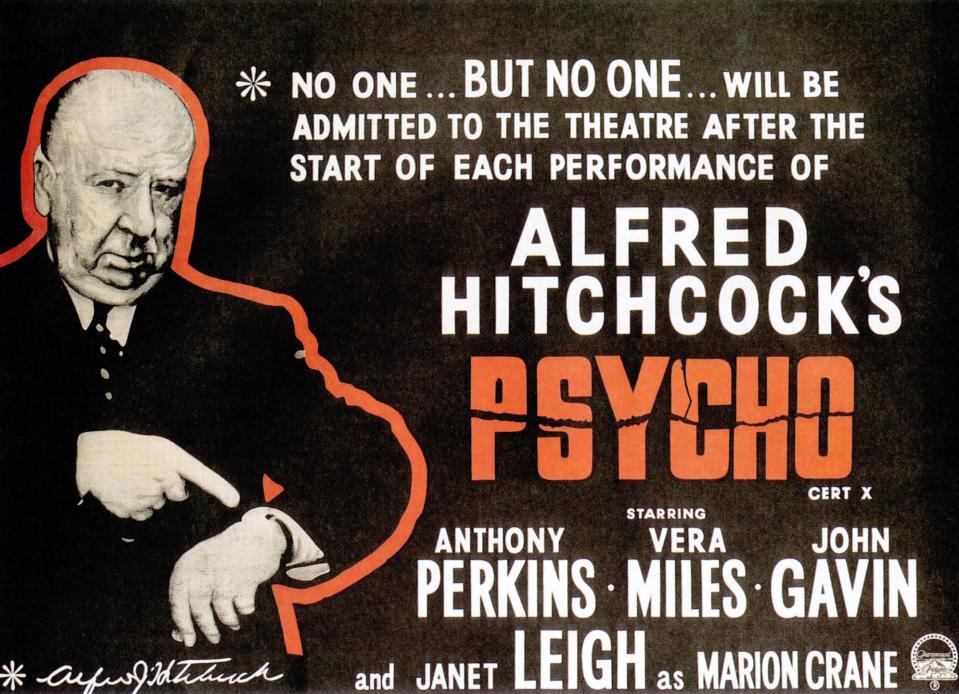

The film has a dark premise, following the serial killer Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm) as he commits murders with a horrifying, voyeuristic twist. Many of the tense, violent scenes are shown through the perspective of a camera viewfinder, reflecting Mark’s work as a photographer as well as a crew member on a film set. It arrived just a few months before Psycho, which also depicted a murderer with an odd fixation on one of his parents.

Read more: Most controversial films of all time

Looked at today, Peeping Tom still has the power to shock. Today, that shock factor comes as much from the thematic depth as it does from the violence. This is a film about the obsession with looking at people, and especially people at their lowest ebb. In a social media age, that couldn’t possibly hit much harder.

Some of the best writing about Peeping Tom was done by the academic Carol J. Clover in her brilliant, seminal horror book Men, Women and Chain Saws. That book contains the essay The Eye of Horror, which discusses at length the “assaultive gaze” of the camera and scopophilia — pleasure derived from looking — which is a key element of Mark’s journey from the subject of his own father’s camera-based experiments to a killer with a love of recording equipment.

But before the critical reappraisal, and before Clover was able to cast her analytical eye over the film’s themes, the reaction to Peeping Tom was swift and vicious. The Daily Worker — now known as The Morning Star — dubbed it “perverted nonsense” and The Tribune advised its readers to “shovel it up and flush it swiftly down the nearest sewer”.

Perhaps the most fervent dismissal, though, came in the Daily Express, which wrote: “I have carted my travel-stained carcass to (among other places) some of the filthiest and most festering slums in Asia. But nothing, nothing, nothing – neither the hopeless leper colonies of East Pakistan, the back streets of Bombay nor the gutters of Calcutta – has left me with such a feeling of nausea and depression as I got this week while sitting through a new British film called Peeping Tom.”

It’s safe to say that critics were offended, appalled and unsettled by Peeping Tom in the same way that many would continue to be by certain horror movies, all the way up to the Human Centipede trilogy of recent years. That would be little comfort to Michael Powell, though.

Read more: Trailer for A Matter of Life and Death restoration

By the time he got to 1960 and Peeping Tom, Michael Powell was cemented as something of a legend in the British film industry. As one half of directing duo The Archers alongside Emeric Pressburger, he had made a series of acclaimed movies including A Matter of Life and Death, The Red Shoes and Black Narcissus. Powell was often the directorial half of the pairing, with Pressburger focusing on the writing and producing side.

Having made his name with these broad appeal movies, Powell found his career hurt in the wake of Peeping Tom’s uncompromising subject matter and savage critical dismissal. He found it difficult to get the greenlight for subsequent projects and, though he did make several more films before his death in 1990 at the age of 84, they did not receive the attention that his prior work did. He had, in effect, been ostracised by the film business due to Peeping Tom.

Interestingly, when Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho was unveiled just a few months later, it received critical acclaim and effectively launched the slasher movie. The 1997 documentary A Very British Psycho puts forward a number of theories regarding the differing reactions, floating the idea that Hitchcock’s decision to eschew press screenings may have helped the movie avoid any sort of negative buzz — which did arrive from press in the UK, but couldn’t stop the box office wave. That, notably, is a strategy that has been deployed by horror films often in the years since.

Read more: 10 things you may not know about Psycho

It certainly could be said that, although Hitchcock reaped the benefits of delivering a more explicit, violent horror movie than the world of Hammer or the Universal Monsters, it was Powell who laid the groundwork.

Peeping Tom has now, however, been fully turned around following a steady reappraisal in the 1970s and routinely appears on lists of the best British films ever made, as well as the best horror movies. Its reputation has been entirely restored, and rightly so.

Martin Scorsese is a high-profile fan, declaring that Peeping Tom — alongside Federico Fellini's 8½ — says “everything that can be said about filmmaking”. In a similar way to Clover, Scorsese said Peeping Tom shows the “aggression” of recording and “how the camera violates”. Scorsese’s regular editor Thelma Schoonmaker was in fact married to Powell in the later years of his life.

Read more: Schoonmaker on her relationship with Scorsese

Six decades after it first received one of the angriest critical receptions of its time, Peeping Tom is well worth another look. Along with Psycho, it helped establish the slasher formula that would go on to power John Carpenter’s Halloween and the subsequent boom in the sub-genre. More than that, though, it’s a compelling and prescient take on the power of the camera, as well as the seductive, intoxicating quality of watching people at their most vulnerable and scared.

As Mark chillingly says: "Do you know what the most frightening thing in the world is? It's fear."

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies