Thelma Schoonmaker: Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Irishman’ is 'not Goodfellas' (exclusive)

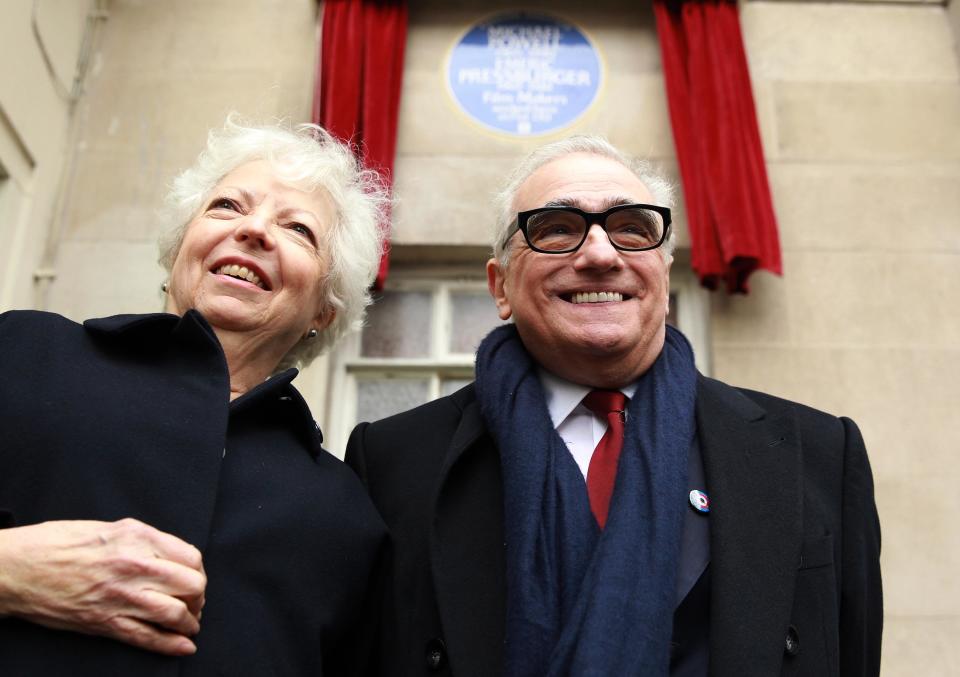

BAFTA and Oscar-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker is going to be honoured with the Fellowship at the EE British Academy Film Awards on Sunday.

Awarded annually, the Fellowship is the highest accolade bestowed by BAFTA, and former award-winners include Alfred Hitchcock, Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, Billy Wilder, Martin Scorsese, and Schoonmaker’s husband, Michael Powell. It’s a big deal, basically.

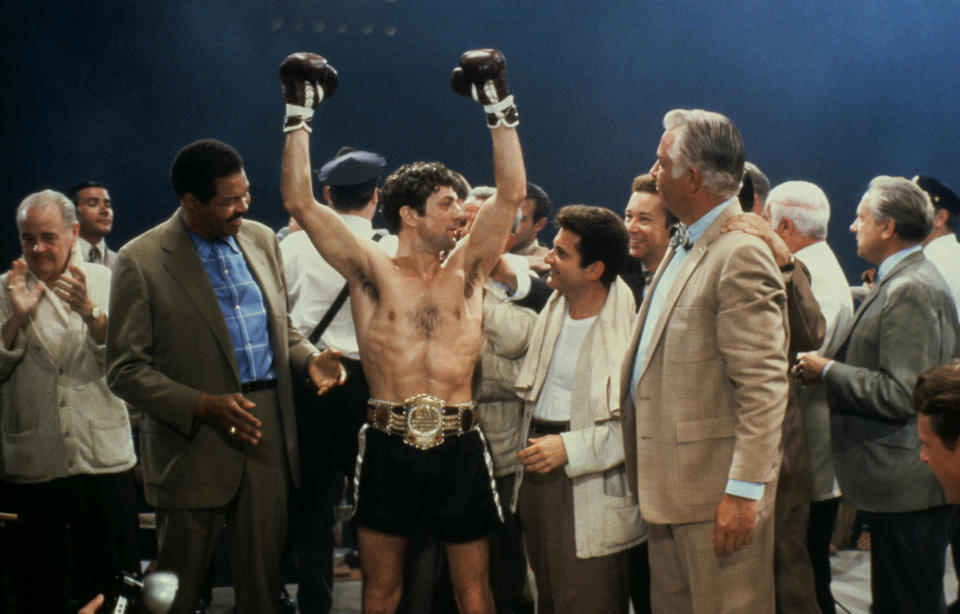

And, if anyone deserves to join those iconic names, it’s Thelma Schoonmaker, Martin Scorsese’s editor since 1980’s Raging Bull (for which she won the Best Editing Oscar).

In addition to Raging Bull, Schoonmaker’s name appears in the credits of half of your favourite films, including Goodfellas, Casino, Wolf Of Wall Street, and so many more. Her credit’s about to appear in The Irishman, and Schoonmaker wants to make it clear to Yahoo Movies UK that it’s unlike anything her and Scorsese have ever made before. Especially Goodfellas.

“The Irishman is not Goodfellas,” Schoonmaker says. “And that’s what they think it’s going to be. It’s not. It is not Goodfellas. It’s completely different. It’s wonderful. They’re going to love it. But please don’t think it’s gonna be Goodfellas, because it isn’t.”

What it is going to be, is groundbreaking – pushing de-aging technology to its very limits, as Schoonmaker reveals exclusively to Yahoo Movies UK. And, as with any cinematic evolution, the pioneers are having to be brave.

“We’re youthifying the actors in the first half of the movie. And then the second half of the movie they play their own age. So that’s a big risk.”

“We’re having that done by Industrial Light and Magic Island, ILM. That’s a big risk.”

“We’re seeing some of it, but I haven’t gotten a whole scene where they’re young, and what I’m going to have to see, and what Marty’s going to have to see is, ‘How is it affecting the rest of the movie when you see them young?’”

“Interestingly, we’ve only been able to screen for very few people, because they’re wearing some things on their faces, and on their clothes, that tracks their movement… Nobody minds. Nobody minds watching them play young, because they’re gripped.”

“Very few people have seen it, because we can’t show it to a big audience. But the characters are so strong, it doesn’t matter – it’s really funny. I don’t know what it’s going to be like when we get it all – that’s the risk.”

“And it’s an expensive project, [Netflix are] taking a risk there.”

But Schoonmaker’s career is full of risks, and pioneering moments. We sat down with the iconic editor for a career-overview interview, covering films as important as King Of Comedy, After Hours, Bringing Out The Dead, Goodfellas, Casino, Raging Bull and many more.

If you’re a cinephile, welcome to heaven.

Yahoo Movies UK: So, I made my first movie last year and working with the editor was my favourite part.

Thelma Schoonmaker: Oh yes, it’s most directors’ favourite part. It’s certainly Scorsese’s favourite part.

It feels to me like it’s a space where magical moments can happen, where amazing accidents can happen…

Accidents are great. We love them.

Were there any memorable moments in any of the films you’ve worked on, where there have been those magical accidents?

You know, it just accidentally happens, we put together two things together, and ‘Wow!’ That really is great.

Marty [Scorsese] loves that on the set, when an actor does something that’s not expected, or something that just happened to happen. He loves that, he capitalises on it. He says, ‘Oh, that’s great. Let’s go further with that.’ But, yes, accidents are very important.

Marty thinks like a director when he conceives with the film, when he co-writes it, but when he directs, he’s thinking like an editor all the time, and then he directs the editing with me.

He says the films are made then. They’re really made in the editing room. What he loves is he can trust me to do the best for his work, and we collaborate intensely together, we shape it. As you know, you drop scenes, you have to shorten things, you link things, you have to move things around, ‘Maybe that will be better as the first thing in the movie.’

So it’s a fascinating, constantly changing, and inspiring thing to do. I’m glad you understand how important it is.

Oh, absolutely, it’s thrilling. Can you think of a moment when you’ve actually surprised Scorsese with something you’ve brought?

I mean, there have been times when I’ve shown him something. Say a scene is way too long, it’s wonderful, but it’s way too long, and I’ll come up with a sort of special way to shorten it and he’ll go, ‘Wow, okay, that works.’

But that’s my job, you know, that is my job. I often make two or three edits for him. Sometimes I’ll make six before he comes in. I do the first assembly. Then when he comes in after shooting is when we start working together, and so sometimes make I’ll six edits for him, because there’s so much rich footage. We could go that way, we could go that way, and then he looks at those six and he chooses two, or and we start re-editing again.

That’s really cool.

That’s very much an important part of my work, to find solutions. Moments might be great, but they’re not working in the body of the movie. Dropping scenes is the worst for us, it’s like cutting off your leg.

I’ll bet.

Oh, it’s awful. Yeah, we’ve dropped some great scenes, and Marty doesn’t believe in director’s cuts, he fights to the death to get what he wants. But one film he allowed me to put all the stuff we had to drop off on the DVD…

After Hours, right? I love After Hours.

After Hours! I said we have so much beautiful footage here, can we please put it on the DVD and he finally allowed that! [laughs]

I’m such a fan of that film, it has such a unique energy.

It’s great!

Did you take a new approach with that movie? I know Scorsese was working with a new DP, but in terms of the edit energy?

Yeah.

It almost feels like if there was no After Hours, there’d be no Goodfellas…

You know, that may be true. He did want to be very fractured with it, because that’s what’s going on in Griffin’s mind. For example, the key drop. At one point, this woman drops the key down to him on the street. We spent days on that shot, we tried 15,000 different ways of dropping that.

Marty shot it with a very specific… he wanted to be a very special moment. He does a lot in his films, there’ll be one little thing like that, that’s kinetic but it has great symbolic importance.

So, we just sweated blood over that thing. But he did want it to be a nightmare, because it was. Marty himself had even experienced that wild taxi ride, where the money flew out the window, you know? He had had that experience himself [laughs].

So he wanted to make it very abstract and weird and crazy, and everybody is crazy in that movie. We loved that, it was fun to cut, man it was fun.

You didn’t cut Taxi Driver, but you did cut Bringing Out The Dead, which feels like it was influenced by Taxi Driver. Were you influenced by that movie?

Yes, I would say so, because it’s the streets of New York. Yeah, it is.

That’s the one film that I wish would be recognised. His films take a long time to be recognised. Raging Bull took 10 years. It was badly reviewed.

A lot of his movies are the same, except for Taxi Driver, Goodfellas and Wolf. They were all immediately recognised because they’re so powerful and entertaining.

But all of them have been rediscovered. For example, Age of Innocence, when it came out people poo-pooed it, but now there’s a new version of it that just came out, and everybody thinks it’s great. King of Comedy – disaster, disaster!

Yeah, I’m really interested in that, because that was your first experience of this – because obviously Raging Bull got you the Oscar…

Yes, it did get Oscars. But it didn’t get him one. But no, you’re right. I mean, King of Comedy was a disaster at the box office.

Did you guys know you’re taking a risk when you were editing it?

Marty felt that he wanted it to be like a TV show, because that’s what the whole milieu was. So he wanted to make it particularly uninteresting visually, really more like TV of that time, to reinforce the world that that Rupert wanted to be in.

So we knew that was different, and that people might not get it, and they didn’t. And now everybody loves that movie. So, sometimes as an artist, you have to wait and it’s painful.

Marty’s always been able to stay alive because he’s learned how to walk that difficult tightrope between art and commerce. My husband never learned that, because [Powell and Pressburger’s] first films were made during the war, everybody left them alone.

Then, when The Red Shoes came out, Rank hated it and tried to kill it. And my husband didn’t understand it. You have to try and understand them and keep your avenues open; he burned all his bridges.

I’ve seen Marty in meetings with people where I would just get up and walk out, and he says, ‘George, that’s a very good idea, but I couldn’t make that movie.’ Which means you’re not saying ‘That’s really stupid,’ which is what my husband would say.

You don’t insult them, you say, ‘Oh, that’s a great idea, but it’s not my cup of tea.’ He’s brilliant at doing that.

To jump to Goodfellas, it’s an astonishing piece of editing, the confidence is overwhelming. Did you feel confident when you were putting it together?

Oh, we knew it was going to be a great one.

Yes!

And, you know, the wonderful thing is that my husband got that movie made, because Marty couldn’t get it made. All the studios kept saying to him, ‘Take out the drugs.’ And he said ‘The drugs are the story of the movie, we can’t take it out.’

He tried three times to sell it, and he was in despair. I came home to my husband and I said ‘Marty’s really having trouble’, and he said, ‘read me the script’ – because my husband, he could see, but his eyes had degenerated which meant he was not able to read.

So I read him the script. He said, ‘Get Marty on the phone,’ and I did – it was a Sunday, the one day I got off! – and he said, ‘Marty, you have to make this movie. This is the most brilliant script I’ve read in 20 years, you have to make this movie.’ Marty went in one more time and he got it made.

My husband died before he saw it, but he got it made, and it saved me. Because when my husband died, I didn’t want to live anymore, and I had to come back to Goodfellas.

Marty shut the movie down, because he loved Michael so much, to let me take him back to England. I didn’t want him to die in America.

He waited two months, until Michael died, and he shut the movie down, the editing, and then when I came back, I knew if I didn’t go back and help Marty, my husband would kill me.

So, I went back and it pulled me out of my grief, and so it’s a film that has much resonance, you know? It’s just a shame that Michael never saw it, he would have loved it.

I’ll bet, and that film is going to live forever…

Everybody says ‘I’m just going to put it on for 10 minutes,’ and then they watch the whole thing.

But, you know, The Irishman is not Goodfellas, and that’s what they think it’s going to be. It’s not.

Oh, that’s interesting.

It is not Goodfellas. It’s completely different. It’s wonderful. They’re going to love it. But please don’t think it’s gonna be Goodfellas, because it isn’t.

What’s the runtime on The Irishman at the moment?

We’re still editing it, we don’t know how long it’s going to be.

I’m just intrigued because it feels like Netflix offers a lot more freedom in that respect…

They do, they’ve been great.

And I know Wolf of Wall Street had a cut that you guys liked that was four hours, and you gradually chipped away…

That happens a lot on our movies and that’s okay, because that’s the way the movie was made. There were so much improvisation. You can’t always say, ‘Oh, we can’t improvise there’ or ‘You have to stop improvising because this scene can only be five minutes long!”

So, you have to go with it, and you have to live with it, and let the film tell you what it is. It’s very common to have to cut the film down from that length.

I guess what I’m asking is, do you still have a sense of discipline with The Irishman, or is there that temptation to keep it longer?

It’s a different kind of movie, it’s episodic, it’s not narrative. When you do a narrative film, you’re always saying, ‘Oh well, you know, we could slim that down, we could move the shot, maybe we should integrate that, maybe we should flashback with that.’ That’s not the way this movie is.

It actually came together very quickly, it’s very different. You will see. It’s extremely different and it really works, which is very exciting.

One last question on The Irishman, Scorsese said that Netflix is taking risks with The Irishman what is the biggest risk on the project for you?

Well, we’re youthifying the actors in the first half of the movie. And then the second half of the movie they play their own age. So that’s a big risk.

We’re having that done by Industrial Light and Magic Island, ILM. That’s a big risk.

We’re seeing some of it, but I haven’t gotten a whole scene where they’re young, and what I’m going to have to see, and what Marty’s going to have to see is ‘How is it affecting the rest of the movie when you see them young?’

Interestingly, we’ve only been able to screen for very few people, because they’re wearing some things on their faces, and on their clothes, that tracks their movement… Nobody minds. Nobody minds watching them play young, because they’re gripped.

Very few people have seen it, because we can’t show it to a big audience. But the characters are so strong, it doesn’t matter – it’s really funny. I don’t know what it’s going to be like when we get it all – that’s the risk.

And it’s an expensive project, they’re taking a risk there.

You see all the alternate takes obviously, so you know better than anyone – what is it about Leonardo DiCaprio that makes him so special, in terms of his collaboration with Scorsese?

What Leo has done is he’s just given himself over to Marty, he loves working with Marty. He wants to learn from him. And so he he takes direction wonderfully. And he’s just grown, you know, as an actor. He’s wonderful, and he’ll do anything for Marty – anything. I think it’s just he’s so open to direction, he thrives on it.

Casino had kind of a weird response, in that some people said it wasn’t Goodfellas…

That’s right.

…But some people said it was too similar to Goodfellas, it was strange. How did you feel about that criticism at the time?

You know, Marty had been through terrible criticism all his life, the studios didn’t understand him. Taxi Driver, that film almost never got released. He fought, and fought, and fought, he’s been misunderstood for a very long time and it’s been so painful for him.

I can’t tell you the stories of great directors that he admired who insulted him and and said ‘You don’t have it. Why don’t you give it up?’

He told me a story recently of a man who looked at a movie and said, ‘I don’t see anything there, really.’ We’re talking about one of the greatest directors who ever lived…

What was the film, if you don’t mind me asking?

[Schoonmaker waves her hand and laughs]

Fortunately, there were some people who believed in him. Cassavetes, do you know Cassavetes?

Oh, I love Cassavetes.

Cassavetes was so important to Marty. Marty, first of all, learned from him tremendously. When he finally met him, when he first went to Hollywood, Cassavetes gave him jobs. He saw Marty’s first film, that he made for Roger Corman, Boxcar Bertha, which is actually quite a good film.

He said to Marty, ‘Come with me. I want to take you to lunch. You just spend a year of your life making a piece of shit, don’t you ever do that again. You don’t let Hollywood co-opt you. You’re here to make movies about your existence.’ And Marty made Mean Streets.

If he didn’t have people like that, his life in Hollywood might have been different. He could have been co-opted, maybe. And that great artist’s telling him, ‘Don’t do that.’

And then, later, when we made Raging Bull, Cassavetes used to come at midnight – because we would work late at night – and bring big plates of spaghetti, with Ben Gazzarra, they would come in, and he would talk to Marty about his next film.

Then he would say, ‘I want to see this, I want to see this movie’ And Marty would say, ‘Oh God, I don’t want to show it to you yet, it’s not ready.’ Finally, he sent me show it to him, and Cassavetes came out and he said, ‘This is a masterpiece’ and he hugged me. He said, ‘I’m hugging you because I feel like I know you, you helped him edit this movie.’

And I said ‘Well, you’re the person who saved him, you’re the person who said he had to remain an artist.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, who asked him to be so good?’

Isn’t that wonderful? Because, in spite of the fact that he had saved him, there is always the jealousy. There’s always the artistic jealousy – ‘I wish I had made that.’ Oh, I love that story – he was so important to Marty.

You’ve said the first time you watched Raging Bull with Marty, you turned to each other and you couldn’t believe you’d made it…

We said, ‘Who made that movie?’ [laughs]

It felt like it was burned into the screen…

It was! [sighs with happiness]

So can you talk a little bit about what led to that amazing moment, the day-to-day process of editing that movie, piece by piece?

Well, he and I always look at the film the first time by ourselves, always. We never show it to anybody else. Then the second time we do.

But when we looked at that, first of all, the power of it was… I mean, you don’t usually get that power right away in a movie, usually you have to create it.

But what we saw was that Paul Schrader had given us a wonderful script, but he kept cutting to flash-forwards of Jake LaMotta, commenting on what we just saw. Marty and I said right away, ‘We don’t need that. Take it all out and just have him fat at the end.’ And that worked like crazy.

So that’s the kind of thing that goes on when we first see our film. But that one was ‘Oh my.’ And this one too, The Irishman, it’s the same thing, when we looked at it… Wow.

Some you have to work and work and work to get that power but, boy, I’m telling you, the first time we saw Raging Bull… Even the projectionist. You know, they’re very tired and cynical, and the guy opened the portal to the projection booth, and he said ‘That’s some movie.’

Hosted by Joanna Lumley, the BAFTA ceremony will be broadcast on BBC One and BBC One HD at 21.00 on Sunday 10th February.

Read more

The most controversial BAFTA moments

Jon S. Baird says Martin Scorsese acted as a ‘mentor’

Netflix will release Scorsese’s ‘The Irishman for two weeks

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies