2021 was the year when football’s silent majority finally found its voice

Remarkably, the website is still live. Eight months after the European Super League disintegrated in an embarrassing fireball, you might think its founders would be minded to erase all trace of their hubris and humiliation. But perhaps that would be to credit them with too much competence. And so there it remains to this day: “The Super League is a new European competition between 20 top clubs comprised of 15 founders and five annual qualifiers.” Well, good luck with that.

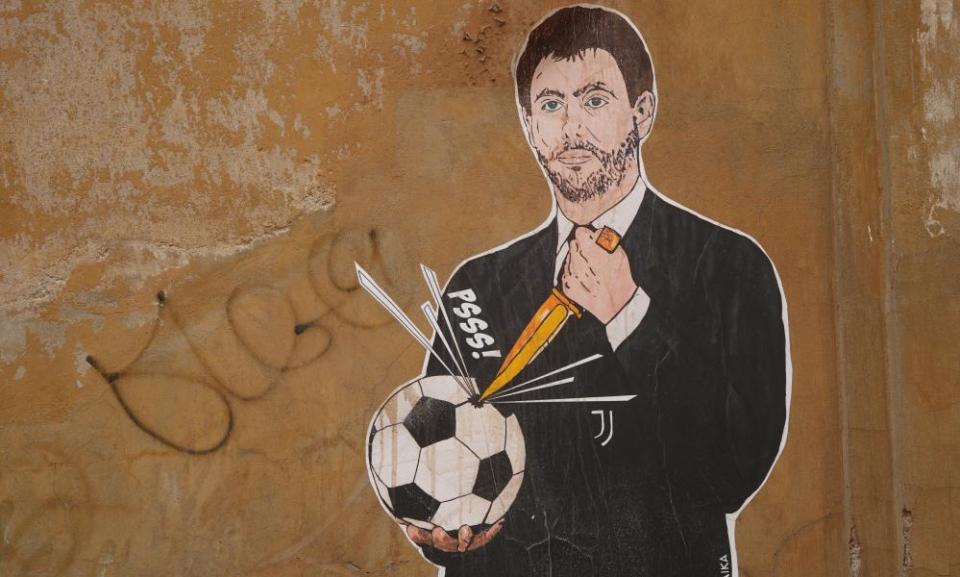

There is, of course, an alternative theory. After all, the Super League is still not quite dead in a legislative sense; certainly not if you believe the loud and persistent avowals of Andrea Agnelli at Juventus, Joan Laporta at Barcelona and Florentino Pérez at Real Madrid, the three remaining hoarse men of the apocalypse. Meanwhile the impulses that generated the Super League – greed, inequality, shifting financial models, Covid – have not disappeared. Perhaps on reflection, that the Super League website is still up is not an oversight, but a warning.

Related: The 100 best male footballers in the world 2021: Nos 100-11

The junking of the Super League may have been a rare moment of harmony in a toxically clannish game – and really, it takes some effort to unite the commentariat, the players, the coaches, the broadcasters, the vast majority of the clubs and the vast majority of fans in revulsion at your product. But in the days and weeks afterwards fans talked openly of a new compact in football, a renegotiated and more equitable power settlement that placed supporters and communities at its heart. As we near the end of one of the most tumultuous and rancourous years in the history of football, how’s that going?

In order to answer that question let’s start at Oldham, who banned three of their own fans from Boundary Park for “promoting dislike” against the club’s owner, Abdallah Lemsagam, before reversing their decision amid a widespread backlash. In his three years in charge, Lemsagam has overseen nine managerial changes and a drop to 23rd in League Two. Explaining his original decision (taken from his home in Dubai), Lemsagam offered this reasoning: “If they are not behaving like every person just watching the game, they deserve to be banned. If you want to protest, nobody can stop you. But why can’t I also ban you?”

In a way, this is the basic ideological faultline of modern football: what is a club and who does it belong to? The romantic will tell you a club is the sum total of its people and its history, that players and coaches pass through but fans remain true, that owners are no more than custodians preserving the institution for the next generation. The three briefly banned fans may feel that Oldham are more their club than Lemsagam’s. But the Companies House filings will tell a very different story.

This is why any attempt to frame the power imbalance in football as one of bigger clubs against smaller clubs, or even bigger leagues and smaller leagues, often obscures as much as it illuminates. Part of the ideological opposition to the Super League was based on the idea of football as a pyramid: a linked whole driving not just investment but aspiration and hope. But within this structure all sorts of complex smaller battles are being fought: between fans and owners, fans and other fans, players and governing bodies, clubs and agents, clubs and broadcasters, broadcasters and fans.

The economist Paul Mason argues that football is not so much a pyramid as a “class struggle”: between fans and players on one side, and the massed ranks of owners, broadcasters, the financial sector and big tech on the other. If one side possesses most of the fervour, the talent and the human emotion, the other side owns pretty much everything else. To modern capitalism, football is essentially a product to be sold, generated, grown, disseminated. Anything that distracts from this fundamental goal – player welfare, fan sentiment, 3pm kick-offs – must by extension be suppressed.

The Super League crystallised this vision perfectly. Too perfectly: in explicitly stating its intention to convert 65 years of European football history into a sort of fungible on-demand content stream, an enclosed circus, a Vegas residency, it horrified not just long-standing “legacy” fans but also advocates of the status quo. The snap-back has been modest but not inconsequential. Manchester United’s first ever fan advisory board will meet in January with Joel Glazer in attendance. Liverpool and Chelsea have announced similar plans. None of this would have happened without the Super League.

So is this a defining moment? Have the owners of the biggest clubs undergone a Damascene conversion to democracy? Or was it merely an attempt to stave off the more far-reaching reforms proposed by the government’s fan-led review, which was unveiled last month with proposals for an independent regulator and a levy on Premier League transfer fees?

Related: Welcome to Covid Britain, where football clubs make decisions on public health | Jonathan Liew

The fierce backlash to the latter proposals from some owners – the Leeds chief executive, Angus Kinnear, derided them as “Maoist” – suggests any meaningful change in the game will have to be won over the stiffest resistance. And besides, what are the available vehicles for change? Fifa? National governments? Fan boycotts? Good luck with any of that.

What is certainly true is that the appetite for change is there. Breaking with football’s traditional model of saturation and endless growth is no longer a niche opinion but a mainstream opinion. “Football must change quickly,” the Real Madrid manager, Carlo Ancelotti, said in a recent interview. “The quality of the show has dropped a lot. The players cannot take it any more. Fatigue, injuries, games that end 10-0. Enough is enough.” This is not a conversation we were having 20 years or even five years ago.

But of course, everyone agrees on the need for change. It is the direction that is contested. For people such as Pérez, Ancelotti’s boss, the answer to competitive imbalance is simply for Madrid to stop playing teams such as Elche and Leganés (“I do not think it’s more attractive to watch unfamiliar teams,” he said during the infamous El Chiringuito interview in April). The answer to player fatigue is to reduce games to 45 or 60 minutes with plenty of ad breaks for the broadcasters.

The Super League itself may have been defeated but its ideas continue to triumph everywhere. In April, Uefa quietly pushed through its new 36-team Champions League format that provides an even bigger safety net to the biggest clubs. Juventus and Paris Saint-Germain may have been toppled in Italy and France, but elsewhere established giants firmly laid to rest any notion that Covid might offer a temporary levelling of the playing field.

Sheriff Tiraspol made it six titles in a row in Moldova, Red Bull Salzburg eight in a row in Austria, Bayern Munich nine in a row in Germany, Ludogorets 10 in a row in Bulgaria. Across Europe, clubs are partnering with cryptocurrency companies with the sole intention of further milking their fanbases for cash. In England, virus-emaciated squads are being forced to play three games in a week because nobody is brave or foolish enough to slow down the gravy train.

And yet even in these grim days of midwinter, it remains possible to glimpse something better. The Super League protests showed us that when fans and players and genuine football lovers speak with a single voice, not even the most powerful men in the game can thwart them.

Eight months on, much of that initial energy may have diffused and dissipated, but the will to change football for the better has not subsided. In time, we may come back to look on 2021 as the year when football’s silent majority finally, tentatively, discovered its voice.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport