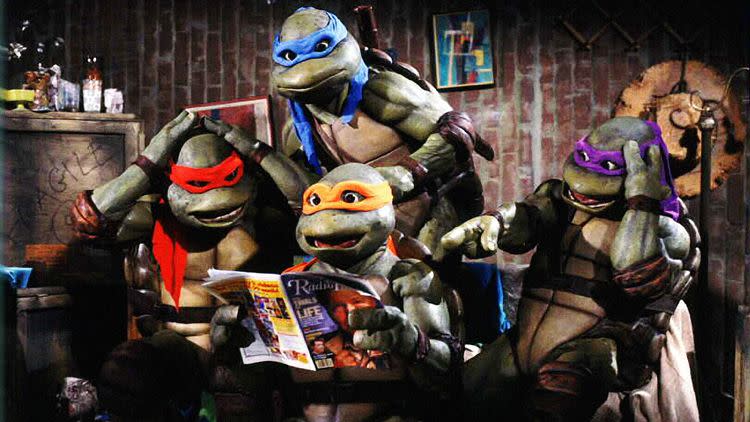

'Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles' at 30: Looking back at the controversy around its UK release

In 1997, over a year after the film had debuted in US cinemas, one of the most underrated Hollywood comedies of the decade snuck out onto video, completely bypassing a theatrical run. There’s a sporting chance you’d not heard of it: A Very Brady Sequel.

Even to get to video, this 12-rated film had required 23 seconds of cuts to get a certificate at all. For it found itself on the wrong side of the British Board of Film Classification’s (BBFC) crackdown on nunchucks, a campaign that had intensified a few years earlier when the Turtles first came to town.

Heroes Vs Ninjas

Nunchucks, then. The traditional martial arts weapon had come to the BBFC’s attention after the success of Enter The Dragon, but it’d come fully into focus with 1990’s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film.

It’d be no understatement to say the whole Turtles phenomenon was a cause of sizeable consternation to British censors, leading infamously to the animated television series and associated merchandise going under the moniker Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles in the UK instead. But whilst the 1990 film got through with the word ‘Ninja’ in the title, British cinema-goers were forced to wait a long time after their US counterparts to actually see it.

Now celebrating its 30th birthday, the movie landed on 30 March 1990 in the US, but wouldn’t hit UK screens until 23 November of the same year. The near-eight-month delay was in part due simply to different times.

It wasn’t uncommon for movies to follow their US release by such time lapses in the UK, in pre-internet days where spoilers and piracy were far, far lesser issues (around the same time, for instance, both Turner & Hooch and Parenthood would trail their respective US releases by half a year each).

Furthermore, whilst hindsight is easy enough, nobody quite saw the success of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles coming, at least not to the level it ultimately reached. When the $13.5m movie barnstormed its way to over $135m at the US box office, it would become the most successful independent film of all time (a record it held until Pulp Fiction shot up a few years later).

Origins

The movie was – after a lot of development to and fro – greenlit by Hong Kong studio Golden Harvest, with production work taking place in the US and at Jim Henson’s Creature Shop in the UK.

But Golden Harvest still needed wide distribution, and no Hollywood studio would touch the film (burned, as the story goes, by the underwhelming grosses for 1987’s Masters Of Universe). Every major turned the movie down, and cameras rolled on the film without a deal in place. Only half-way through filming did New Line Cinema agree to put the movie out in America.

Overseas

This was a crucial development for the UK release.

New Line at this stage was a small company that hadn’t as of yet been taken over by Warner Bros (and it was still a decade or so away from Lord Of The Rings). It had made its money off the A Nightmare On Elm Street series, but didn’t have the safety net of a studio bank account or credit rating.

Taking on Turtles was thus quite a gamble for the firm, and at this stage, it didn’t have tentacles in the UK. A separate British distributor would need to be sought, and that was going to add an additional delay to the UK release.

Read more: Twin Peaks at 30

Had Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles been a studio film, there would have at least been a chance of a closer-together release. But ultimately Virgin Vision acquired the production for the UK market. By the time it came to actually release it at the end of 1990, the movie had become the sleeper hit sensation of the year in the States, and the Turtles themselves that year’s biggest toy craze.

It wasn’t just Virgin Vision that noticed this, of course. The BBFC did as well. Conflict lay ahead: its distributors wanted a children-friendly PG certificate for the film, whilst the BBFC was hugely concerned by sequences including the aforementioned nunchucks, and didn’t want anklebiters watching them.

The-then head of the organisation, James Ferman, insisted on substantial cuts to the film, although not all at the BBFC agreed, with one examiner arguing their young daughter had watched the US version “without being turned on to chainsticks”. There was pressure to revise the entire policy, but Ferman didn’t yield.

In all, one minute and 51 seconds were spliced out of the movie to secure the November cinema release. Not just nunchucks, as it happened, but also the title Turtle Power song was reworked to swap out the word ‘ninja’ and substitute ‘hero’ in its place. Certain moments were reframed too, with the BBFC fearing that British youth would seek to be ninja-influenced. Again, this new cut took a little time to put together.

Hit

The delay, as it happened, didn’t prove detrimental to the film’s UK box office impact, with the movie proving to be a sizeable success (in spite of pretty hostile reviews). But the contribution of the several discussed factors led to it following that of the US by some time.

Incidentally, the story of the censorship of the quickly-made sequel The Secret Of The Ooze in the UK – which involved sausages used as nunchucks being cut out – is detailed at the BBFC’s own website, and it’s a pretty infamous case. It was in the last vestiges of Ferman’s nunchuck crackdown, and the case study is something of a classic (look for the genuine line “since there is real confusion between chainsticks and sausages this sequence needs to be carefully checked”)

Read more: How Honor Blackman set the Bond girl template

The Turtles story, of course, has proven to have further cinematic legs, albeit none of the releases since have been as impactful as the original. The most commercially successful – the 2014 reboot – has nowhere near the fanbase, and nowhere near as iconic a title tune. Nor, notably, any cuts.

But that original film? Its birthday is being celebrated with good cause. A film that was a battle and a half to make, a huge risk to greenlight, and a tougher than expected job to release, three decades on, it remains arguably the Heroes In A Half Shell’s finest big screen work.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies