Netflix series 'Challenger: The Final Flight' reveals there's no villain behind the 1986 disaster

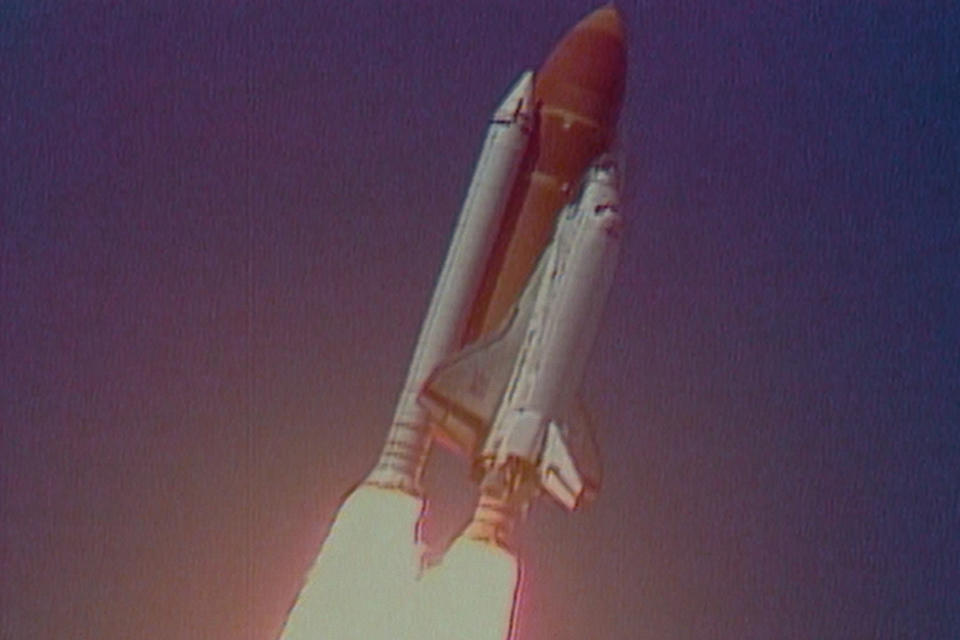

When the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded only 73 seconds after its launch on January 28, 1986, the shock and horror of the tragedy united Americans in mourning. In the weeks and months afterwards, though, the hunt for an explanation led to no small amount of finger-pointing at NASA from the public, the media and the U.S. government.

President Ronald Reagan — who had been a vocal champion of the Challenger mission — formed a Presidential Commission consisting of prominent scientists and astronauts (including Neil Armstrong) to investigate the accident, and the ensuing report revealed how a series of mistakes and poor decisions resulted in the deaths of the seven-member crew in a televised moment that an entire generation of adults, and children, vividly remember.

Three of those now-grown children are Daniel Junge, Steven Leckart and Glen Zipper, the creative team behind the new Netflix miniseries, Challenger: The Final Flight. Premiering on the streaming service on 16 September, the four-episode series provides a step-by-step history of how the Challenger mission came together… and what went horribly wrong.

Watch: ‘Challenger: The Final Flight’ latest trailer and is currently streaming on Netflix

Read more: New on Netflix in September

In the process, The Final Flight illustrates how the disaster can’t be blamed on any single person. “There isn’t one villain,” Leckart tells Yahoo Entertainment. “If anything, the villain would be groupthink and systemic dysfunction. We knew from the beginning that this was going to be a complex story where there wasn’t a binary hero and villain.”

That villain-free approach extends to NASA as an entity, which comes under intense scrutiny during the series, but isn’t singled out as the proverbial “bad guy.” “We didn’t set out to crucify NASA,” confirms Leckart, who co-directed the film with Junge, while Zipper served as the project’s executive producer along with J.J. Abrams.

“We read the entire commission report, and saw how the paper trail went back and how many voices there were in the room. Managing an institution like that is so complex.” And as Junge notes, the Challenger has since become the model for industries seeking to study breakdowns in management structure. “There were human failures, poor decision and hubris, but you see some of those bad human actions within this overall picture of systemic failure.”

The Final Flight is nothing if not thorough in its presentation of the many missteps that preceded the 28 January launch, including serious design flaws that were overlooked, engineering concerns that were overruled and weather conditions that perhaps should have prompted further delays. At the root of it all was NASA’s understandable desire to reignite public interest in the space programs which had waned considerably since Armstrong took that one small step on the lunar surface in 1969.

It was that impetus that led officials to make an unprecedented choice: placing a civilian — educator Christa McAuliffe — onboard the Challenger. “She was the everyperson,” Junge says of the Boston-born teacher, who was selected by the Teacher in Space Project announced to great fanfare by the Reagan administration in 1984. “Rather than make science ordinary, they were trying to bring the ordinary to science and Christa exemplified that perfectly.”

Like any government agency, NASA was also concerned about keeping its budget intact at a time when the Reagan administration was increasingly spending funds on defence projects like “Star Wars” — the nickname given to a planned missile defence system. Over the years, it’s been speculated that NASA delayed the launch date until 28 January to sync up with Reagan’s State of the Union address, which he was scheduled to deliver that evening. But Leckart says that the documentary team’s research didn’t turn up evidence that any members of the administration pressured NASA to get the Challenger in orbit to meet that specific date.

“They never would have rushed a launch to appease the president if there was any danger. Reagan had talked about the Challenger as a ‘Rah-rah America’ moment, but any other president would have done the same. Party aside, you would have seen any president say, ‘Look what we’ve achieved.’” (At the same time, according to several subjects interviewed in the film, Reagan did take steps to try and preserve NASA’s reputation in the Commission hearings.)

If there’s anyone who audiences might perceive as seeming remotely villain-like in The Final Flight, it would be Dr. William R. Lucas. As the director of the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center from 1974 to 1986, Lucas oversaw the Space Shuttle program and pushed to maintain an aggressive launch schedule. As outlined in the film, he also had the authority to overrule any pre-launch concerns, and did so in the case of Challenger, wilfully turning a blind eye to the specific design flaw — one involving the rubber O-rings intended to seal the field joints of the rocket boosters — that was found to play a major role in the explosion.

Lucas appears for an on-camera interview in The Final Flight and stands by his actions three decades later. “Going into space is something that great countries do,” he says in the film. “It’s also risky; you have to take some chances. There’s no way you can account for those seven lives except to say that’s the way development happens… The costs sometimes are very difficult and those lives were it.”

Lucas’s words may sound callous, but Leckart still cautions viewers against seeing him as the Emperor Palpatine of the Challenger saga. “Space travel is inherently dangerous and really difficult, and [NASA] has to make tough decisions. You know when you’re signing up to be an astronaut that you may be risking your life. Three astronauts died on the launching pad before we landed on the moon, but we didn’t stop. Challenger happened, but we didn’t stop. So could he have a sense of contrition? I think he really believes in the decision he made, and stands by it. He doesn’t feel that people deserved to die, but that’s the point. Despite all of our best ignitions, these things unfortunately happen and that’s part of what we’re setting out to do. There’s a risk versus reward scenario that we play out in our mind and we choose to take the risks.”

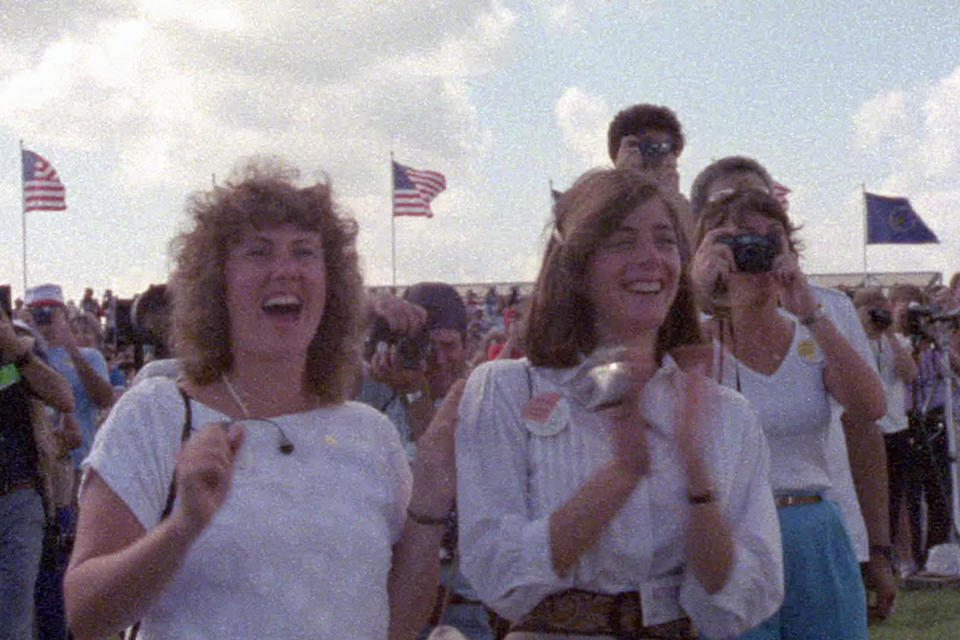

In making the documentary, all three filmmakers had a chance to reflect on their personal memories of watching the Challenger tragedy happen in real time. Both Zipper and Junge remember being in middle school math class when the news broke and teachers were urged to turn on their televisions. “They marched the whole school into the cafeteria and we watched the news,” Zipper recalls. “As traumatic and painful as it was, our teachers recognised it was history that was happening, and we needed to participate in it in some way.” In contrast, Leckart remembers that his elementary school classroom’s television was turned off as soon as the explosion occurred. “We didn’t talk about it; it was just ‘Go outside,’” he says now. “That was really my experience with death. I hadn’t lost a loved one or a pet; I didn’t know what death was.”

The Final Flight purposely avoids showing the famous final moments of the Challenger until the end of the third episode in order to make viewers experience the sheer enormity of the tragedy all over again. “That footage is so iconic, I think people became desensitised to it,” explains Zipper. “Across the first three episodes of the series, we reinvest you in the crew members’ stories, so by the time you see the explosion, it’s imbued with a whole new meaning. It’s hard to watch at that point.” While the directors initially contemplated reconstructing the launch with multiple pieces of archival film footage — including some angles that had never been seen before — they ultimately decided to only use the footage that millions of people at home watched on that January morning.

“It’s probably the longest uncut shot in the series,” Junge notes. “There’s a little bit of new sound design there, but otherwise it’s exactly how it was experienced and re-experienced on the day of the accident. I think that footage has been used in the media in the past quite gratuitously, so we wanted to hold off on it for that reason. We wanted you to experience this in a real-time telling, to the point where it’s almost a surprise when you see it in that moment.”

News footage from 28 January also captures the horrified reactions of the family members of the Challenger crew, including McAuliffe’s parents and her husband, Steven J. McAuliffe. According to the filmmakers, both he and their two now-grown children declined to be interviewed for the series.

“We did send a letter, and we heard back that he appreciated the letter but he’s not really done any press and my understanding is that’s not something he’s interested in doing,” Leckart says. Other family members, among them McAuliffe’s sister, did agree to be interviewed. “They all talked about the steps of grief,” Junge says. “That was a common theme across all the interviews: that idea of disbelief and shock moving to anger and finally to some resolve and level of forgiveness that seemed to be a common theme throughout the interviews.”

Seeing the extended family of the crew members also drives home the diversity of the crew members onboard the Challenger — one of the chief legacies of both that mission and the since-discontinued Space Shuttle program in general. “The shuttle program opened the doors to women and people of color,” Leckart says. “Space was no longer going to be the purview of white male fighter pilots.” That’s one of the reasons for optimism about the future of space flight that the filmmakers hope audiences take away from the story of the doomed Challenger shuttle. “Although there is a cautionary tale within our series, we all agree that we wanted to end this up on an uplifting note,” Junge remarks. “We all believe in space exploration — we just need to go into it wide-eyed.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies