James Bond Day: Why 007 has endured as a movie mainstay and will again

In just one weekend the cinema marquee signage has gone from announcing ‘JAMES BOND TO SAVE CINEMA’ to ‘JAMES BOND KILLED CINEMA’.

Theatrical hopes were high for 007’s touted November 2020 return with No Time to Die (having done that very 2020 thing of postponing back in March). Whilst the latter headlines of a new delay until Easter 2021 miss the wider, global contexts that saw Bond’s studio godparents MGM pull its twenty-fifth Bond movie, the fact is a lot rides on a Bond movie.

As leading cinema chains announce closures and headlines point the Walther PPK at our man James, it is ever apparent Bond does not just represent ever vital revenue and cinema dollars. He represents the very spectacle, event escapism and communal entertainment that mainstream cinema has been predicated on since motion pictures first flickered in the Victorian dark.

Read more: Cineworld announces ‘temporary’ closure after 007 delay

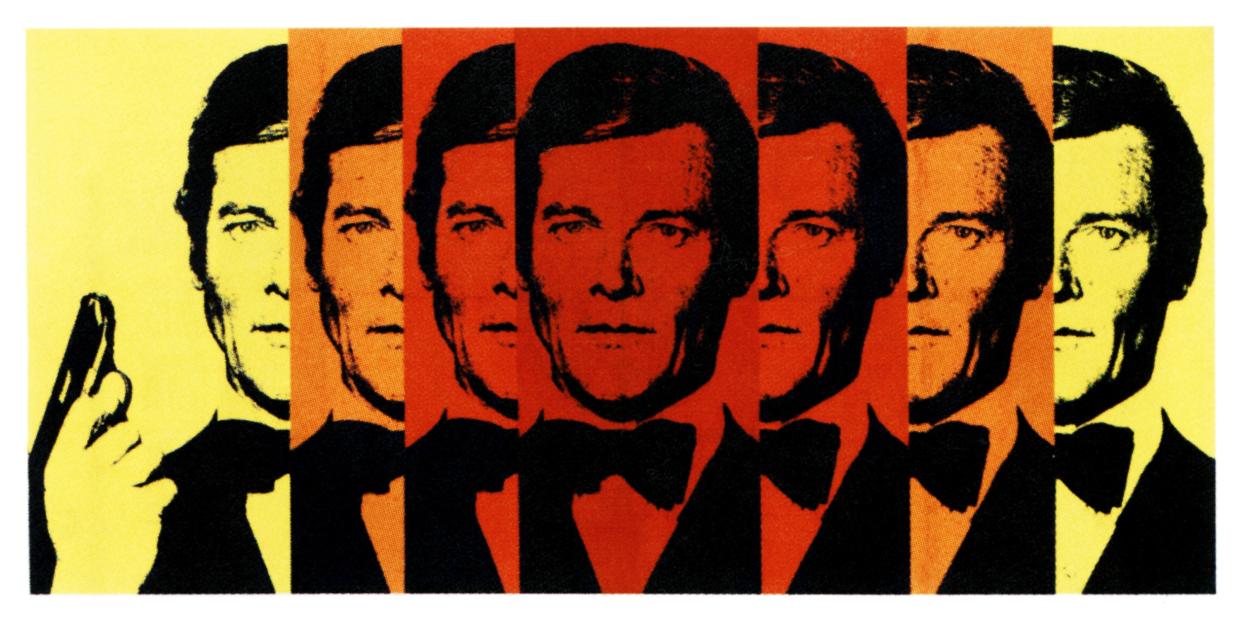

So, as the first Global James Bond Day (marking the anniversary of Dr. No, the first Bond film, released on 5 October, 1962) occurs during a global pandemic and saddening times for global arts and cinema, why has Bond, his movies, headlines, and relevance endured for seven cinematic decades?

Watch: The latest trailer for No Time To Die

Very few film franchises can attest to twenty-five films. The Godzilla series predates 007 by eight years and has stacked up more titles, and the Marvel output is certainly stacking up its chapters (23 instalments of the MCU and counting). Yet, both these franchises are from multiple production teams and creatives. Bond however remains the in-house glory of arguably the biggest, family-run corner shop on the Hollywood lot.

Bond’s initial genesis was as a post-war distraction for a rudderless writer looking to transplant his war-wise world into spiky pulp-fiction for bowler-hatted commuters and long cigarette-clutching housewives. Ian Fleming, his twelve Bond novels and short story collections were not just the literary template of 007, his villains and romances.

It was about a key pop-culture moment garnished by keen Presidents and Prime Ministers that was about to create another moment – when producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman saw the cinematic scope for a world tired of jingoistic war flicks and yesteryear heroes.

Popular culture is a curious beast. Less of a king, James Bond 007 is perhaps the speeding, playboy duke of pop-culture. Fleming’s Bond had success because readers could physically dip into his adventuring world wherever they were in theirs. When the films started firing at the world’s movie screens, it was a different era of exhibition and movie attendance. There were more picture-houses and attendance rates, but less movies. Compared to today’s tight exhibition windows, films once ran, double-billed and returned with different frequencies to today.

Read more: George Lazenby pays tribute to Sean Connery on his 90th birthday

Add a very different era’s ability to almost make a 007 film for every year of the 1960s (just not a reality on any level in 2020) and the movie Bond’s first act at the movies compounded his importance to pop culture forever more. That and the fact EON Productions assembled the best league of hip young cat designers, composers, artists, editors, and writers in a beat of time where everything aligned.

The history of Bond is also a chronicle of entertainment consumerism. From the railway station booths selling Fleming’s paperbacks in the 1950s to the cinema queues and drive-ins of the 1960s, the televised Bonds in the 1970s, the video-store and home retail Bonds of the 1980s to the VHS boxsets and laserdiscs (ask your nan) of the 1990s, the subscription movie channel Bonds and internet forum fans of the 2000s, the DVDs, Blu-rays and social media lecterns of the 2010s, and the streaming, multi-device platform world and repertory cinema comeback of Bond’s 2020s – 007 has endured because technology has forever taken him onwards.

One could suggest it was television – where the onscreen Bond first originated in CBS’s Casino Royale (1954) and where Fleming himself once assumed would be 007’s natural home – that sealed the real legacy of Bond. When the films started broadcasting at peak time slots this became the valid moment where audiences did not just go to Bond. He now came to them.

The warm memories of 1970s family holiday cinema treats in cold seaside towns soon also became the curtain-closing, chocolate box traditions of sitting down at home on holiday afternoons with Dad, Auntie Sylv and your Connery-fancying Mum. When nothing was open on a British Sunday afternoon, a televised Bond film trended before trending was even a thing.

The 1981 UK TV premiere of Live and Let Die alone amassed 23m viewers. When The Queen joins with Daniel Craig to jump out of a helicopter for Danny Boyle’s brilliantly bold overture to the London 2012 Olympiad, that was not solely a reflection of Bond’s place in British cinema. That was a nod to Bond’s hold on the British people and the cultural tapestry the character, his films and tropes are now woven into.

The films themselves have also reflected their times. Or tried to be a few beats ahead of them. The very month the first film Dr. No (1962) premiered in London with a spy-fi minded caper about S.P.E.C.T.R.E. nuclear reactors and disrupting the Mercury space programme, the very real Cuban Missile Crisis flares up. When the oil crisis of the 1970s kicks in, 1974’s The Man with the Golden Gun is already there with an energy crisis plot. Whilst the labour shortages, strikes and politics that dogged Britain in the 1970s left the nation short of power, manufacturing and bin collections, Bond responds by giving the world a global slideshow of distracting locations, transcontinental characters, tailored glamour, swim shorts and sun.

Read more: Sean Connery crowned the best James Bond of all time

Never underestimate the two-hour vacation that a Bond film meant for those kids and parents in those high street cinemas. It is no coincidence that the 1970s Bond films barely show the UK beyond Bond’s apartment and establishing shots of Whitehall. By the time of 2012’s Skyfall, the Queen’s Jubilee and that Olympiad, London has become the proud, recurring sandbox for Daniel Craig.

When Jaws and Star Wars reign supreme in the 1970s, Bond does not just respond by making Moonraker (1979). He looks at the teenage, younger audiences engaging their dollars with big summer films again – so those late 1970s Roger Moore Bonds react with bigger, physical, and summery capers. By the time of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and its vintage-minded, B-movie escapades Octopussy (1983) cracks its own story whip accordingly.

And when The Bourne Identity (2002) ups Bond’s action game – whilst maybe forgetting its own influences are editor Peter Hunt’s 1960s Bond movies – Quantum of Solace (2008) responds by hiring Bourne’s stunt co-ordinator. That is not Bond bootlegging other movies. That is the Broccoli brand knowing where action cinema and the tastes for it are at any given time.

It's #JamesBondDay everyone...

A post shared by James Bond 007 (@007) on Oct 5, 2020 at 1:30am PDT

A perfect example is the Daniel Craig era itself. His tenure has featured the information age, energy shortages in poorer regions, funding terrorists and the dangers of surveillance. However, it is the structure of story and a longer-term sense of project that sees the sixth Bond really reflect his era.

Read more: No Time To Die is 'a love story'

In an age of binge-watched, box-set dragons and stranger BMXs, Bond’s once familiar standalone mission motif has been usurped by story arcs and connective narrative tissue. A smaller detail or character from one film is soon a key player later. Suddenly it is no longer five separate films, but a fifteen-year project of action cinema. Bond does not need a Marvel-esque extended universe after all. His very registry of twenty-five movie titles that have been part of our movie lives and motion picture memories is pretty extended already.

Cinema is always a personal transaction and one that – unlike a music gig or a theatre play – we can do either solo or with others. But it is that communal nature of cinema where a Bond film and Bond’s movie legacy is really forged.

The 007 movies are a quite different beast on the big screen. In a large auditorium they roll and punch differently with the gaze and smiles of a gathered audience pinging across the action like a DB5. We should not blame Bond right now for endangering the very medium that needs him. Health fears aside (although the reports of cinema-caught illnesses are as rare as popcorn right now), other industry, financial and even national politics have fed into Bond’s enforced sabbatical across the globe.

But Craig will see out the school year sometime – with an eye on finding the new head boy afterwards. Goldfingers crossed.

No Time To Die is now coming to cinemas in April, 2021.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies