From ‘Arabian Nights’ to ‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah’: Disney’s most controversial songs

Disney’s musical animations remain the company’s calling card. Countless classic songs have been produced for its films over the past near ninety years, from early earworms like ‘Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?’, featured in 1933’s short, The Three Little Pigs, to the unstoppable force of Elsa’s ‘Let It Go’ and ‘Into the Unknown’, from the Frozen movies.

The ‘Disney Renaissance’ of the 90s produced a clutch of some of Disney’s best-known songs, including ‘Under the Sea’, ‘Be Our Guest’ and ‘Friend Like Me’. These came courtesy of song writing power duo, Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, who first rose to prominence with the success of their musical, Little Shop of Horrors.

As Disney releases its documentary Howard on Disney+, celebrating the life and career of the late lyricist, we look back at times when famous Disney songwriters, despite the hits, didn’t always hit the right notes.

‘Arabian Nights’ (Aladdin, 1992)

As recently as the 90s, Disney made uncomfortable calls when it came to song lyrics. The opening number from 1992’s Aladdin generated outrage over its description of the film’s Middle Eastern setting. Upon its cinematic release, the lyrics of ‘Arabian Nights’ began: “Oh, I come from a land / From a faraway place / Where the caravan camels roam”, before delving into offensive territory with, “Where they cut off your ear / If they don’t like your face / It’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.”

Read more: The best musicals to watch after Hamilton

Following public criticism, the Walt Disney Company made the unusual decision to change Howard Ashman’s lyrics, post-release, to an alternate version that most remember now from the home video release: “Where it’s flat and immense / And the heat is intense” – but the studio did stick with the “barbaric” lyric, claiming it purely referenced the climate.

Despite this controversy, composer Alan Menken and lyricist Tim Rice (who stepped in, following Howard Ashman’s death from AIDS-related complications in 1991) went on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Song with the iconic Aladdin-Jasmine duet ‘A Whole New World’. This also remains the only Disney song to have won the Grammy Award for Song of the Year.

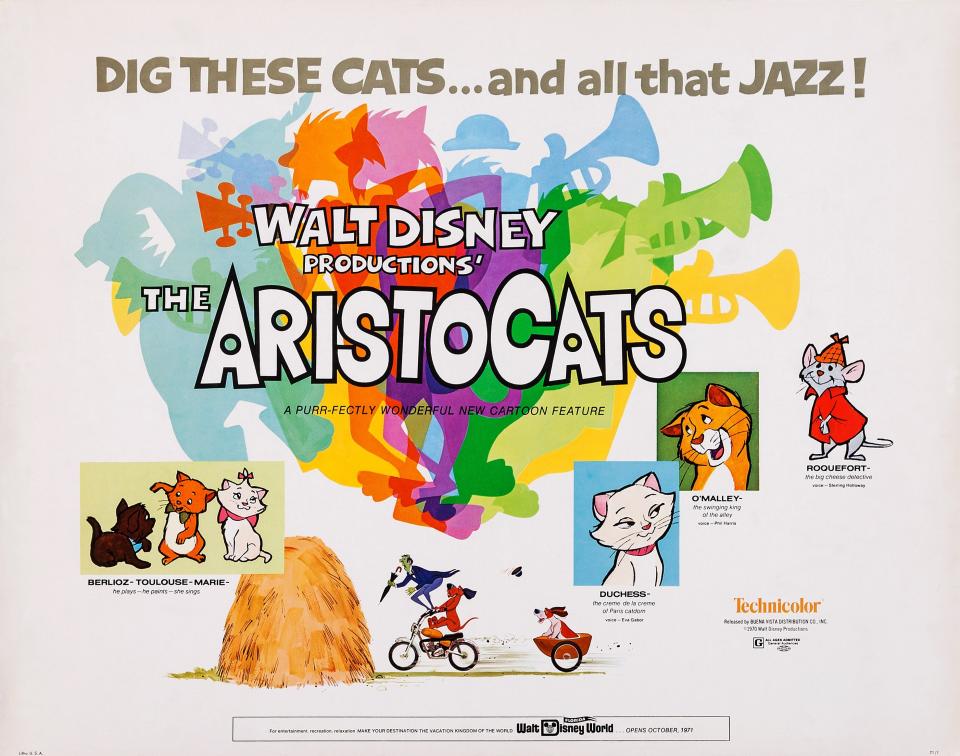

‘Everybody Wants to Be a Cat’ (The Aristocats, 1970)

There’s a particular character and part of this song that’s dated badly due to its crude cultural stereotyping. Despite being considered quite a bop, and one courtesy of the legendary Sherman Brothers, Siamese cat Shun Gon’s contribution to the song is sung in a stereotypically heavy Chinese accent (by white American voice actor Paul Winchell). While playing the piano with chopsticks, Shun Gon exclaims: “Shanghai, Honk Kong, Egg Foo Yong / Fortune cookie always wrong!”. Yes, because all of those words strung together sum up the entirety of the Chinese culture… These lyrics have since been cut from more recent releases of the song.

The leader of ‘Everybody Wants to Be a Cat’, Scat Cat, was a role designed for trumpet-playing Louis Armstrong, but ill health meant Disney had to replace him with Scatman Crothers – and Satchmo Cat became Scat Cat.

‘The Happiest Home in These Hills’ (Pete’s Dragon, 1977)

For possibly the most (intentionally) upsetting subject matter of a Disney song, this number from 1977’s Pete’s Dragon surely deserves that dubious honour. From song-writing team Al Kasha and Joel Hirschhorn, its catchy nature, as well as Disney’s way of jollifying hideous characters and their motives by giving them a good song and dance, hides quite a few evils. The abusive hillbilly Gogans, who bought Pete to work on their farm, describe all the awful things they’ll do to the runaway boy when they find him. This includes, but is not limited to: gagging him, drowning him, hanging him, eating him and tying him to a railroad track. And let’s not forget – “Gonna paw him, saw him in half, when he cries out for mercy, we'll just laugh.”

It’s quite something to realise these lyrics are gleefully sung by actors including Oscar-winning Hollywood star Shelley Winters, chewing the scenery, and Jeff Conaway – Kenickie in Grease the very next year!

‘Hellfire’ (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1996)

This controversial Disney song is by far the most adult in nature. Pious, twisted Judge Claude Frollo sings of his lust for the gypsy Esmeralda and how it torments him (yup!). The frank terms in which he refers to this “fire in my skin”, the “burning desire” that “is turning me to sin”, are often seen as making a bit of a mockery of the family-friendly ‘U’ rating The Hunchback of Notre Dame received. As he’s further consumed by licentious thoughts that he claims he’s too pure to have, Frollo strokes Esmeralda’s scarf against his cheek and is teased by a sexy spectre of her in the flames of his fireplace, both of which really add to the mood. The climax (ahem) of the song sees Frollo exclaim that she must, “Choose me or / Your pyre / Be mine or you will burn”.

The backdrop of the scene, in Notre Dame, saw lyricist Stephen Schwartz include confessional terminology in the song such as “Beata Maria”, “mea culpa” and “Kyrie Eleison”, highlighting Frollo’s blasphemous nature – and the rather provocative nature of this song.

‘Let Me Be Good to You’ (The Great Mouse Detective, 1986)

Did you know that there’s a strip-tease in a Disney animated movie? Step forward The Great Mouse Detective, an obvious take on Sherlock Holmes and one of the studio’s offerings in its difficult period before the Disney Renaissance began at the end of the decade with The Little Mermaid. Just as with ‘Hellfire’, what’s depicted on screen adds to the less child-friendly tone of the song. As Miss Kitty sings that she’ll “take off all my blues” to a very appreciative audience at the Rat Trap, she whips off her skirt to reveal a gartered leg and wiggles her bum in the air, promising that, “There’s nothin’ I won’t do / Just for you”. The particular meaning of that message seems pretty clear!

Written and performed by Melissa Manchester, ‘Let Me Be Good to You’ is also an obvious ode to Nancy’s scene from Oliver!, where she changes the mood of the tavern’s patrons with her rousing rendition of ‘Oom-Pah-Pah’.

‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ (The Lion King, 1994)

Controversy for a different reason now. ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’, sung so iconically by Timon and Pumbaa in The Lion King back in 1994, had Disney embroiled in legal proceedings with the family of musician Solomon Linda. His 1939 South African hit ‘Mbube’ was borrowed by Pete Seeger of The Weavers in 1952, who misheard the title (and renamed it) as ‘Wimoweh’. This was then sampled in the chorus of The Tokens’ better-known 1961 Number One record, ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’.

Read more: The best way to watch the MCU

Disney duly settled the dispute in 2006, paying a lump sum to his estate in lieu of past royalties, but it’s unlikely the family received benefits from 2019’s photorealistic remake of The Lion King as South African copyright law ends 50 years after death: Linda died in 1962, and Disney’s proffered five-year extension ended in 2017.

‘Pink Elephants on Parade’ (Dumbo, 1941)

‘Pink Elephants on Parade’ is a song entirely about being drunk. Moreover, it’s the titular baby pachyderm on this particular journey of discovery after Timothy Q. Mouse fails to realise the barrel of water they’re drinking from has been spiked with champagne. Both Dumbo and Pinocchio from the previous year, contain these quite disturbing scenes of children getting drunk/high, thought to carry moralising messages from the Walt Disney Company. This sequence ended up cut from Tim Burton’s recent remake, but there’s a nod to it from Danny DeVito’s ringmaster, who warns the clowns, “No booze near the baby”.

“Seeing pink elephants” has been a well-known euphemism for the hallucinations one might experience when drunk since the early 1900s. Alongside the song, the scene in Dumbo also showcases a memorable, surrealist animated sequence where elephants shrink, swell and morph into pyramids, snakes, belly dancers and ice skaters.

‘Pink Elephants on Parade’ lyricist Ned Washington actually picked up the Best Original Song award at the previous Academy Awards in 1940 for the song that has become most synonymous with Disney – ‘When You Wish Upon a Star’.

‘Savages’ (Pocahontas, 1995)

Pocahontas is one of Disney’s most obviously controversial films in its recent canon, given the way the story of this real-life Native American woman was altered to erase any of its less palatable events, in favour of a shoehorned-in, false romance with John Smith.

The song ‘Savages’ was one that could, quite understandably, strike entirely the wrong tone – as it did with the voice of Pocahontas, actress Irene Bedard, whose initial reaction was, “Why did we have to go there?” as she considered the word “so fraught”. The song does make it clear that the charge of “savage” is being laid down at both doorsteps, and Stephen Schwartz’s lyrics highlight the misunderstandings between the two cultures, but there’s lots of racially-charged language with talk of skin that’s “hellish red” (although at least Governor Ratcliffe is an out-and-out villain) or a “milky hide”.

And boldly using the title ‘Savages’ is rather tone-deaf, given the painful associations it has for America’s native community, playing on offensive stereotypes that haven’t progressed beyond ‘Cowboys and Indians’.

‘The Siamese Cat Song’ (Lady and the Tramp, 1955)

In what makes The Aristocats a case of déjà vu, Siamese cats were first portrayed offensively in 1955’s Lady and the Tramp – and this time, they had a whole song to themselves. Si and Am (yup!) are the sneaky felines that deviously mess up Aunt Sarah’s house knowing that Lady will take the blame. All the while they sing, swaying in symmetry, and grinning malevolently. The cruel stereotype of their buck teeth, slanted eyes and thick accents is just as unwelcome as Shun Gon’s matching characteristics, 15 years later.

Read more: The best Pixar shorts on Disney+

Bizarrely, not only did Peggy Lee write the song, but she also performed it as both cats. The lyrics don’t amount to much, being in a crude broken English, and opening with the nonsensical, “We are Siamese if you please / We are Siamese if you don’t please”. Unsurprisingly, this song did not make the cut for the recent Disney+ remake.

‘Someday My Prince Will Come’ (Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, 1937)

Even at Disney, purveyors of traditional fairy tales, its princesses have more recently been affected by feminism and the changing role of women in society. This song, from Frank Churchill and lyricist Larry Morey in the 1930s, is all about waiting to be rescued by a prince – very passive, and very passé.

“And away to his castle we'll go / To be happy forever I know” is no longer what young girls are being encouraged to dream of – we now live in a world of Meridas, Moanas and Elsas, who take charge of their own destinies and don’t see bagging a prince as their life goal. Real-life Disney stars Kristen Bell and Kiera Knightley have even spoken out against this dated depiction.

Walt Disney also had voice star Adriana Caselotti under a controversially strict contract, which prevented her from taking on other roles, as he didn’t want to “spoil the illusion of Snow White”.

‘Song of the Roustabouts’ (Dumbo, 1941)

It’s surprising that this song isn’t spoken about more frequently as an obvious example of dated stereotypes and language in a Disney song that tip over into what is now considered overt racism – but then Dumbo has a couple of those.

‘Song of the Roustabouts’ plays over an incredibly uncomfortable depiction of animals and exclusively black labourers (who aren’t even given the courtesy of faces) setting up the circus on a stormy night. But Frank Churchill and Oliver Wallace’s lyrics make things decidedly worse, with talk of them being “happy-hearted roustabouts”, even though they “never learned to read or write”, “don’t know when we get our pay” and – oh yes – “slave until we’re almost dead”. This is unquestionably one of the most jarring Disney songs to watch in its original context, and recognise the kind of racism that was perfectly acceptable (and went unnoticed) in the 1940s.

‘A Spoonful of Sugar’ (Mary Poppins, 1964)

Controversial by association rather than anything else, ‘A Spoonful of Sugar’ is here to represent the entire musical catalogue of the Mary Poppins film, loathed as it was by the character’s creator, P.L. Travers. With Saving Mr Banks, Disney itself has produced a behind-the-scenes account of the making of one of its most beloved films and the tussle involved with the very protective – and very unimpressed – author, Travers. As far as she was concerned, her Mary Poppins was certainly no quirky, singing Julie Andrews type.

The Sherman Brothers, who won two Oscars for their work on the music for Mary Poppins, tried their best to sway Travers by creating songs with phrases from her work, including ‘Feed the Birds’ and ‘A Spoonful of Sugar’ – but Richard Sherman remembered that, “She didn’t care about our feelings, how she chopped us apart”.

‘What Makes the Red Man Red?’ (Peter Pan, 1953)

This is another infamously offensive song that tends to slip people’s minds, and one that truly solidifies Peter Pan’s awful representation of Native Americans overall. One of the major problems with this song is, of course, its title – worth noting at a time when NFL side the Washington Football Team has finally stepped back from its former, oft-protested ‘Washington Redskins’ moniker.

Read more: The best child-friendly documentaries

The lyrics of the song (by hit machine Sammy Cahn) continue to be cringingly insensitive, with the Lost Boys asking in its pre-amble, “What Makes the Red Man Red?”, “When Did He First Say ‘Ugg’?” and “Why Does He Ask You ‘How’?”.

It continues with nonsensical words, and exaggerated, stereotypical hopping, whooping and dancing, although Wendy, as a girl (a more offensive term is used) is pushed to go and collect firewood while the boys get to join in. By the time Disney decided to release a Peter Pan sequel in cinemas in 2002, Return to Never Land had quietly retired the “Injuns” of fifty years prior.

‘When I See an Elephant Fly’ (Dumbo, 1941)

This is a genuinely brilliant song, with clever lyrics, seriously tainted by unnecessarily offensive decisions made on screen. The fun word-play with “house fly”, “horse fly” and seeing “a peanut stand”, as well as the gentle teasing nature of the song, is ruined by the seriously unwise decision to have this performed in an African-American ‘jive talk’ style by a group of crows. And to make matters worse, their leader is called Jim Crow, as in the Jim Crow state laws that mandated racial segregation in the Southern United States until 1965. Yikes. If you can bear any more poor choices, Cliff Edwards, who voiced Jim and was also known as Jiminy Cricket, was a white singer.

Despite the serious issues with racism in Dumbo and its musical score, this did not stop Frank Churchill and Oliver Wallace from winning the Academy Award for Best Original Music in 1942. Disney+ has added an “outdated cultural depictions” warning at the beginning of the film.

‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah’ (Song of the South, 1946)

From Disney’s most controversial film comes a classic song that everyone can hum – ‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah’ even won a Best Original Song Oscar for composer Allie Wrubel and lyricist Ray Gilbert. Outside its origins in Song of the South, it simply seems a carefree and relaxed song about a happy day: “Plenty of sunshine headin’ my way”. But context’s a killer, as its singer, Uncle Remus (James Baskett), is a problematically uncomplicated, cheerful black man who was previously enslaved. To really nail its colours to the mast as a film that denies the horrors of slavery, storyteller Uncle Remus goes so far as to say at one point, when reminiscing about how things used to be, that, “If you’ll excuse me for saying so, ‘twas better all around”.

Read more: The Disney film that will never be on Disney+

Disney has been hiding Song of the South in its vault now since 1986, and Disney executive chairman Bob Iger confirmed that it will never see the light of day on Disney+. Curiously, the company was happy to use the less “complicated” part of its legacy in the Br’er Rabbit stories for the theming of its very popular Disney Parks log flume ride, Splash Mountain – but 2020 has finally put paid to that, with Disney announcing an upcoming re-theming around 2009’s The Princess and the Frog.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies