How chaos created classics for Hollywood's unluckiest studio RKO

1933 marked an excellent year in terms of output for Hollywood studio RKO Pictures: Releases included iconic monster flick King Kong; Little Women and Morning Glory, starring new studio star Katharine Hepburn (the latter of which gave the actress her first Oscar), and Flying Down to Rio, the musical that launched the celebrated partnership of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

But the studio was in a financial hole, struggling to survive the Great Depression, and that year lost its promising but short-lived production chief, David O. Selznick, who was largely responsible for RKO’s surge of quality movies. This year acts well as a snapshot of a studio where chaos reigned and yet, despite this, enduring classics like Citizen Kane, Top Hat and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon were produced. But how was this possible?

RKO Pictures was the most unstable – and oft forgot – member of the ‘Big Five’ studios from Hollywood’s Golden Age (MGM, Warner Bros., Paramount Pictures and 20th Century Fox were the others). These five conglomerates owed a lot of their clout to the fact they were vertically-integrated production houses, distributors and movie theatre owners, all rolled into one.

Read more: Why Akira is one of the greatest animations ever

This guaranteed a shot at a lot more box office than their smaller competitors, and was something that certainly helped keep RKO afloat during its struggle to survive.

Watch: Citizen Kane is one of the biggest Oscar snubs ever

RKO was also a major breeding ground for talent and innovation, from releasing Becky Sharp, the first full three-strip Technicolor feature film, to championing screwball comedy with Bringing Up Baby, fine-tuning the art of B-movies and producing a fine run in film noir. The studio also had a distribution deal with Walt Disney to release his studio’s feature-length animations, and nurtured the careers of stars like Cary Grant, Maureen O’Hara, Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Mitchum and John Wayne.

With over twenty of the studio’s best features currently available to watch on BBC iPlayer, and David Fincher’s upcoming Netflix film Mank set to go behind the scenes of the troubled making of Citizen Kane, what were the main misfortunes and scandals that befell RKO?

Charles Koerner: King of RKO

RKO Pictures’ main problem, throughout its tumultuous thirty-year production period, was a lack of steady and constant leadership. With a growing list of production chiefs passing through, there was never enough time (and certainly rarely enough budget) for almost any of them to take charge and consistently deliver high-quality films. Some of these earlier men were brilliant Hollywood creatives (David O. Selznick, Merian C. Cooper) – but it wasn’t enough without proper stability.

The studio continuously fought to stay in the black, spending seven years in receivership during the 1930s before clawing itself back into the clear in 1940. But the year after 1941’s critically-triumphant (but financially draining) release of Citizen Kane, it seemed the studio’s luck was finally to change. Charles Koerner came on board to lead RKO through the box-office boom of World War II, offering strong direction with a new focus on hiring in major stars that the studio currently lacked, either on a freelance basis or on loan from other major studios that held their contracts. That’s how Ingrid Bergman and Bing Crosby appeared together in 1945’s The Bells of St. Mary’s, which became the highest grossing film in RKO’s history. It’s also how stars like John Wayne, Gary Cooper and Frank Sinatra first came on board with the studio.

But this successful streak wasn’t to last – Koerner, who had transformed RKO from a studio with annual profits of just over $700,000 in 1942 to more than $12m four short years later, died of leukaemia in February 1946. With rumbles of anti-Communist paranoia ahead of the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in 1947, and eccentric aviation and movie magnate Howard Hughes poised to disastrously take control of the studio in 1948, Koerner’s death marked the beginning of a decline from which RKO would never truly recover.

Citizen Kane: The trials of making RKO’s masterpiece

As David Fincher’s Mank is due to recount, iconic movie Citizen Kane – a film on which RKO would later cement its reputation as a heavyweight in Hollywood (sometimes) – suffered a stormy production period.

Screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, who had collaborated with Orson Welles on initial ideas for this project, as well as agreeing to work as an uncredited “script doctor” to produce a first draft of the screenplay, rebelled against the contract he had signed. This contract gave sole authorship credit to Welles and was to help sell the idea that the twenty-five-year-old “boy wonder” was capable of doing it all himself.

Read more: Tom Hardy’s best performances

But the unreliable (and likely, alcohol-fuelled) Mankiewicz later flew into a rage and performed a volte-face that saw him threaten Welles via the medium of trade paper adverts, as well as lodge then retract – then dither – over a formal complaint with the Screen Writers Guild. The studio solved this dilemma by formally instating credit for Mankiewicz.

However, a more ominous threat overshadowed Citizen Kane. Media tycoon William Randolph Hearst caught wind of striking similarities between details in the screenplay and his own life, from which Mankiewicz had allegedly drawn inspiration. More incriminatingly, Mankiewicz had been a member of Hearst’s inner circle during the 1930s, before a falling out – and the word “rosebud” allegedly had an extremely personal connection to Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies’, anatomy… As well as making an enemy for life in Hearst, the mogul also blocked any mention of Citizen Kane in any of his outlets, including newspapers and radio stations, and rejected any advertising.

Despite this drama, Citizen Kane would later go on to become heralded as the greatest film of all time. It was also nominated for nine Oscars, and won one – for Best Original Screenplay.

RKO: The ‘B’ grade student

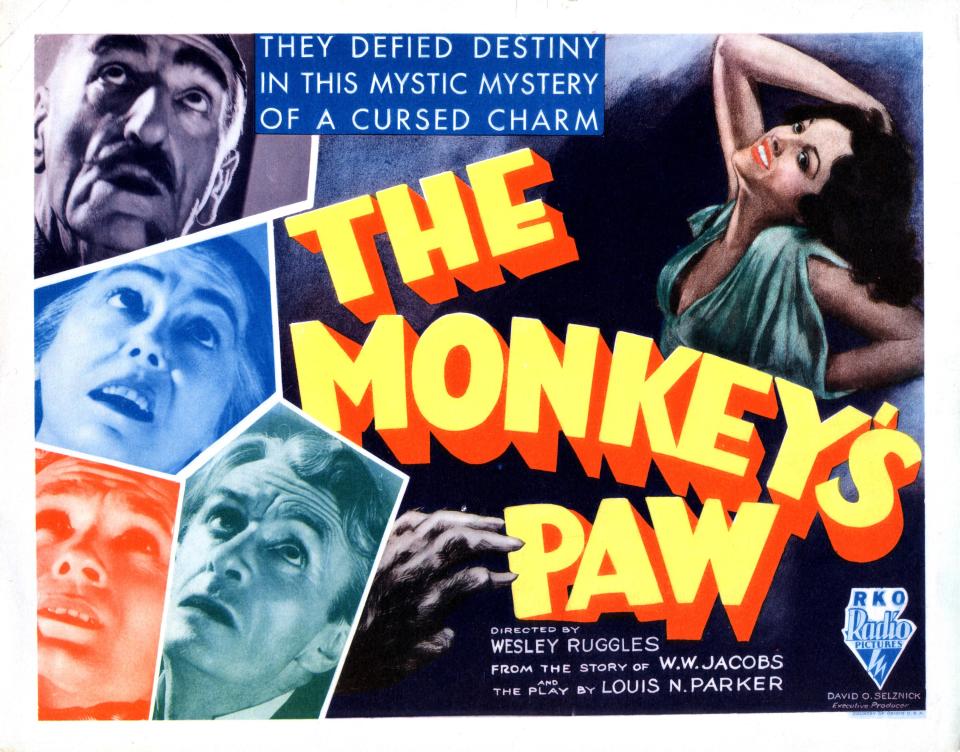

RKO’s wildly uneven output was quite something to behold, including its stone-cold classics like Citizen Kane, movie musicals from the dependable partnership of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and co-productions like Hitchcock’s Notorious and Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life. But even the best movies didn’t necessarily make money from the off: Orson Welles’ three-picture deal was was an incredibly costly signing for the studio, and quintessential screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby performed far below expectation. There was also a lot of forgettable filler between these great films – movies like The Monkey’s Paw and Carnival Story – and misfires like Mourning Becomes Electra.

Alongside the bigger, tent-pole titles for its stars though, RKO also made a deliberate choice to focus on churning out a huge number of B-movies during the 1940s. And as the member of the Big Five that most relied upon them, these were made to be good B-movies. As well as solid bets like Westerns, and picking up Johnny Weissmuller to star in more Tarzan movies, RKO showed a flair for horror. Under producer Val Lewton’s watchful eye, the B-movie standard was raised with seminal pictures like Cat People, The Body Snatcher, Bedlam and I Walked with a Zombie. Unfortunately, a corporate shake-up following Koerner’s death left Lewton unemployed and, in ill health himself, he was dead by 1951.

Film noir was also a (cheaper) calling card of RKO, which produced Stranger on the Third Floor, Nocturne and They Live by Night among others. It also helped confirm the success of studio-grown talents like Robert Mitchum and director Edward Dmytryk – although both men were unable to avoid their own impending scandals.

RKO’s two in ‘The Hollywood Ten’

“The Hollywood Ten”, a group of industry figures blacklisted for refusing to testify at the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in October 1947, included a sole director and a sole producer, both of whom were successful figures at RKO. Indeed, director Edward Dmytryk and producer Adrian Scott had been responsible for RKO’s biggest film that year, Crossfire. Dmytryk had also had great success with surprise hit Hitler’s Children and Tender Comrade. Because of that, the whole undertaking seemed to smear RKO’s reputation more than that of other studios, as Communist paranoia truly took hold in Hollywood, turning friends against one another and destroying careers.

Both were fired by RKO and sentenced to prison time for their lack of co-operation. Dmytryk reconsidered and in 1951 answered the HUAC’s questions, naming party members and accusing others of pressuring him to add Communist material to his films – including Scott. Welcomed back into the fold, Dmytryk’s later directorial output included The End of the Affair and The Caine Mutiny. Scott turned to journalism and writing for television before the British subsidiary of MGM hired him back into a production role in 1963.

RKO’s star scandals

RKO was not short a star scandal or two throughout its history. Some of the more notable stemmed from actors that had had their careers developed by the studio and were under contract with them exclusively – as it almost always was during the studio system era of Hollywood.

Katharine Hepburn was a major acting talent, an icon of Hollywood’s Golden Age, and one of RKO’s biggest-ever discoveries. A winner of four Best Actress Oscars, Hepburn enjoyed parts in films at RKO like A Bill of Divorcement, Morning Glory and Little Women. However, the winning combination of her and Cary Grant in 1938’s delightful screwball comedy, Bringing Up Baby, somehow fell flat.

Read more: The greatest gangster film ever made?

The same year she was labelled “box office poison”, identified in an article in the Independent Film Journal as a star that was not worth her hefty salary. RKO was only too happy to let Hepburn buy out the rest of her contract and head back to Broadway to lick her wounds. Hepburn would return to Hollywood before too long though, with The Philadelphia Story up her sleeve and a long-standing partnership with Spencer Tracy (both on and off-screen) to look forward to at MGM.

Robert Mitchum was another talent cultivated at RKO. Following his performance in 1944’s Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, Mitchum nabbed a seven-year contract at the studio. He began in Western B-movies before finding a natural home in the closest RKO had to a signature genre – film noir. Crossfire and Out of the Past boosted the trajectory of his career, until he was arrested for marijuana possession in 1948. The kind of trouble that could easily ruin stardom during these days, Mitchum spent a week in county jail. But the scandal seemed to ignite his fandom, and RKO capitalised on it by making him travel around the country on a promotional tour, and rushing out his next two films – Rachel and the Stranger and The Red Pony.

His conviction was eventually over-turned in 1951, when it was revealed to have been a set-up to catch multiple Hollywood figures. Sadly, Mitchum’s drinking was soon to get him fired, but his career rallied and he went on to appear in classic films such as The Night of the Hunter, Heaven Knows, Mr Allison, and The Longest Day.

Howard Hughes grounds RKO’s flight

It was Howard Hughes’ takeover of RKO in 1948 that finally torpedoed the studio. A fading post-war box office didn’t help, but Hughes was facing lawsuits following on from his ill-advised attempt to sell on the studio to racketeers, as well as the government’s ban on studios forcing “block booking” of film packages from cinemas outside their ownership – a tactic upon which the Big Five (as distributors) relied to make a chunk of their change. This ruling effectively ended the old Hollywood studio system.

Hughes was also a difficult character, battling OCD as well as interests outside of movie-making – namely aviation and attempting to seduce, control and essentially own multiple leading ladies. Stars such as Jane Russell (for whom he infamously engineered a bra), Jean Simmons and Jane Greer (he derailed her career for rejecting his advances) were victims of Hughes’ incessant attention and cruel behaviour.

Hughes also spelt disaster for the studio by making a series of poor choices, from meddling movie micro-management to scalping studio staff levels and allowing Walt Disney to end RKO’s distribution deal with the company, which had been in place since 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. As a staunch conservative, films he saw as insidiously Communist were pulled, rampant paranoia bled throughout the RKO lot, and Hughes suspended and investigated many staff members for party links, striking their credits if he felt it justified.

Read more: Tom Cruise’s most dangerous stunts

Hughes may have ended up with almost sole ownership of RKO by 1954, the first near-full owner of a studio since Hollywood’s earliest days, but due to his actions it meant far less than it had done a decade prior, and Hughes ended up selling the studio to General Tire in 1955. The studio would limp on until early 1957, before production was permanently shut down.

RKO’s legacy

In its lifespan, RKO Pictures achieved just two Best Picture Oscars – for Cimarron in 1931, and The Best Years of Our Lives in 1946, which was, in reality, a Samuel Goldwyn production. John Ford was the sole recipient of a Best Director Oscar for an RKO picture – 1953’s The Informer. This pales in comparison to the rest of the Hollywood studios.

Its certified classics have exploded in popularity in the intervening years, but they didn’t necessarily bring home the bacon when it was most needed by RKO. It might be a smaller list of hits than its rivals (many of which are still standing), but their quality is undeniable. The studio seemed to attract an enormous pile of talent, both in front of and behind the camera. Alongside its bankable stars, the studio welcomed Irving Berlin and George and Ira Gershwin to Hollywood to work on the music for Astaire-Rogers vehicles, Willis O’Brien to wield his special-effects magic on King Kong, Walter Plunkett to furnish its stars with his lavish and iconic costumes, and Max Steiner to begin a musical output that still inspires composers for film today. Directors Alfred Hitchcock, George Cukor, Howard Hawks and female pioneer Ida Lupino all produced excellent work at RKO.

Director Cukor reflected in a later documentary that the studios were very accessible, and impressive “in retrospect” – so perhaps that smaller, less coherent managerial vibe allowed creative juices to flow more freely? Director Pandro Berman seemed to agree, declaring that RKO “made almost anything and everything”, with no over-arching house style to keep the studio in a particular box.

It certainly seems that while the corporate level of RKO Pictures seemed to pre-occupy itself with disaster after disaster, its talent could at least successfully get on with – if not the business of movie-making, then the art of it. And that, after all, is what counts.

23 classic movies from RKO Pictures are available now to watch on BBC iPlayer. David Fincher’s Mank launches on Netflix in 2020.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies