Pete Weber's path to the Nashville Predators broadcast booth: Baseball, nuns and Notre Dame

A baseball field at H.T. Custer Park, in the west-central Illinois railroad town of Galesburg, is the closest Michael Peter Weber ever came to a long-term relationship with his first true love.

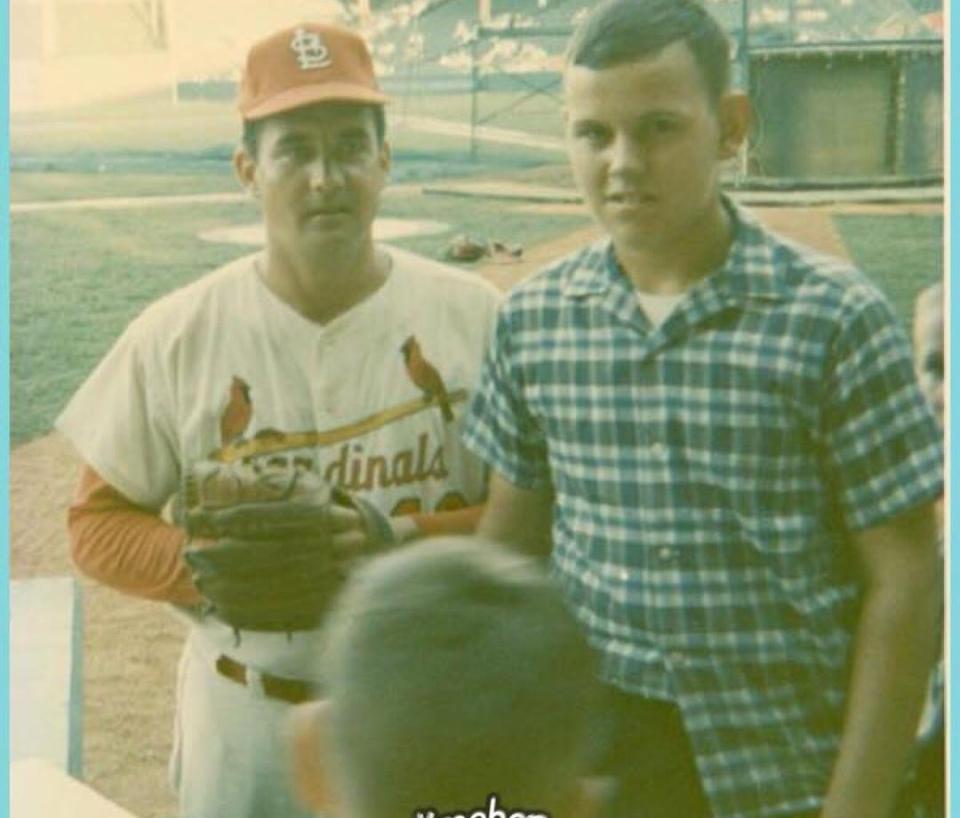

That's where, one afternoon in 1969, an 18-year-old better known as Pete Weber showed up — unannounced and uninvited — to try out for the St. Louis Cardinals, his favorite team.

That's where, with a single swing of the bat, Weber's childhood baseball fantasies took one last breath. The home run he hit in front of scouts that day came to rest 20 or 30 yards beyond the right-field fence. In the front yard of a real future major leaguer — and a future friend — named Jim Sundberg.

"I knew him before he got gray hair," said Sundberg, a three-time MLB All-Star who first met Weber when the two played against each other in Little League. "He very easily could have hit one in the front yard."

"He wasn't afraid to try something," said Mike White, another one of Weber's childhood pals. "A lot of kids had dreams but never tried it."

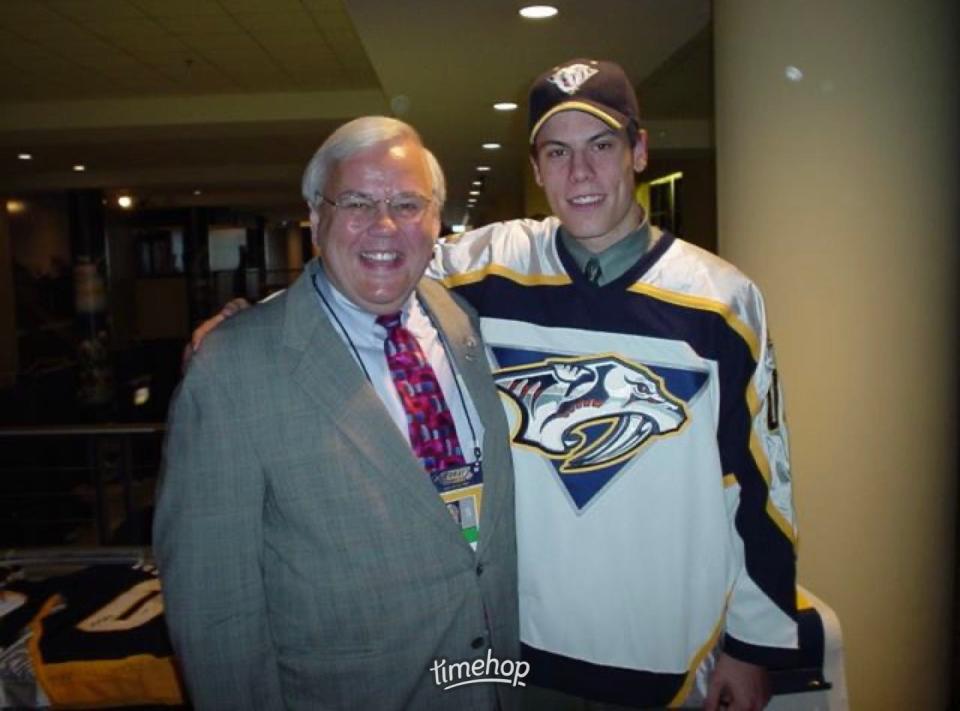

Pete Weber, the radio voice of the Nashville Predators since the day the franchise began play in 1998, tried it.

"Pete was an average player," White continued. "But he had a healthy self-confidence. He loved the fact the right-field fence was short. He could pull the ball."

Weber's career as a broadcaster has been well-documented.

But how did that career come to be?

Start with that railroad town in west-central Illinois where Weber hit his last home run.

Pete Weber: 'I could hit'

Weber knew well before he finished rounding the bases that day that he wasn't major league material.

"I could hit," he said. "That was the only redeeming factor of my game."

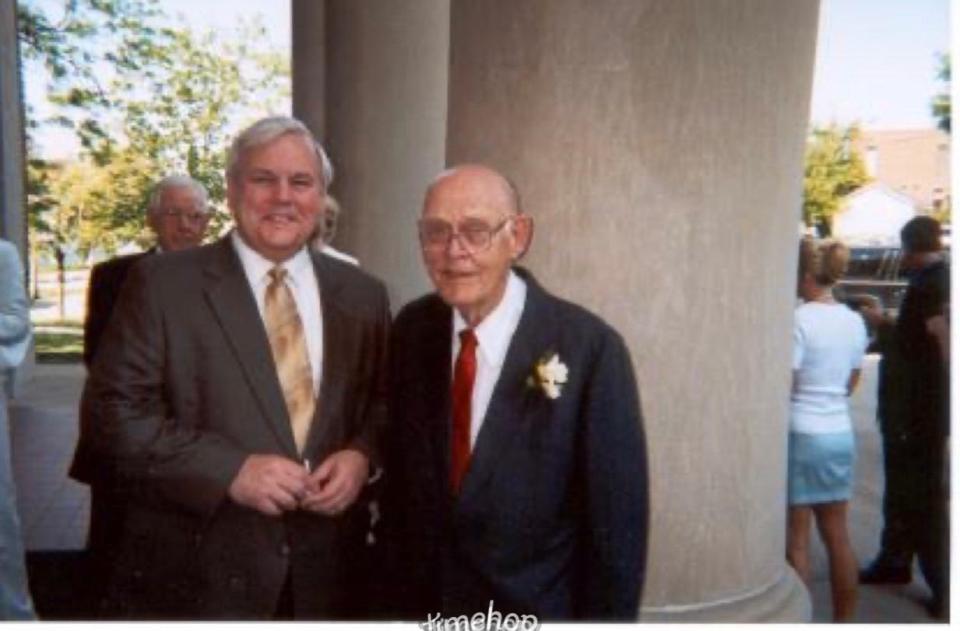

Soon he was off to college at Notre Dame, where his father, John, had gone to become a football player.

"He did not turn into Rudy," Weber said, referring to famous Notre Dame walk-on Rudy Ruettiger.

He turned into an architect who later married Weber's mother, Eileen, a Galesburg native.

Together they had a son who could talk, which is what Weber has been doing for 25 years for Predators fans. And in the years before that, for fans of the Los Angeles Kings, Buffalo Sabres, Buffalo Bills and Buffalo Bisons, among others.

Sundberg and Weber became closer friends after Weber got into broadcasting and Sundberg into pro baseball. Sundberg even put Weber's name in for a Texas Rangers broadcasting job one year.

"I think he had a desire to always do baseball," Sundberg said. "And then he ended up in hockey."

Now Weber is calling his 16th postseason for the Predators, who are facing the Vancouver Canucks in the first round of the NHL playoffs. He has no retirement plans.

Pete Weber sends telegrams to St. Louis Cardinals dugout

A transistor radio rested next to a bed inside a split-level home at 1317 North Academy St. in Galesburg. That's where voices belonging to Jack Buck, Harry Caray, Joe Garagiola and Bob Elson crackled through speakers. That was Pete Weber's bedroom, where his first two true loves — the Cardinals and announcing — collided.

Five out-of-town newspapers — the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Boston Globe, Chicago Daily News and Chicago Tribune — were delivered to the house each day.

Weber liked reading about his favorite players, such as Lou Brock and Stan Musial.

But he loved listening to his favorite announcers talk about his favorite Cardinals.

"Fifty-thousand-watt stations," Weber said. "I was so entertained by the announcers."

Weber was such a diehard fan of the team that he reached out to Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst three times.

During one 1968 World Series game.

Via telegram.

Weber was 17 years old.

PETE WEBER'S OLD PAL: 'Going out in a blaze of glory:' Inside Terry Crisp's last Nashville Predators radio broadcast

MR. 2,000: Pete Weber hits broadcast No. 2,000 with Nashville Predators. Here's how he got there

"He was upset with the way Schoendienst was coaching," said Angelo Ippolito, who also grew up with Weber in Galesburg. "So he got on the phone and fired off a telegram to him in the dugout. He fired off, if I recall, at least three telegrams during the game, asking him what he was doing."

'They put a microphone in front of me'

Earlier that fall, Pete Weber made his radio debut in Mackinaw, Illinois, because someone had to pee.

Weber's Costa High School football team was playing Deer Creek-Mackinaw. Weber, a lineman, wasn't on the field because of a pinched nerve in his neck.

"The guy doing play-by-play got a call from nature because he'd had too much iced tea, or beer," Weber said. "So they put the microphone in front of me."

Weber climbed the ladder to the press box, the first steps in a career he hasn't left since.

A career that almost ended before it began.

Pete Weber gets fired

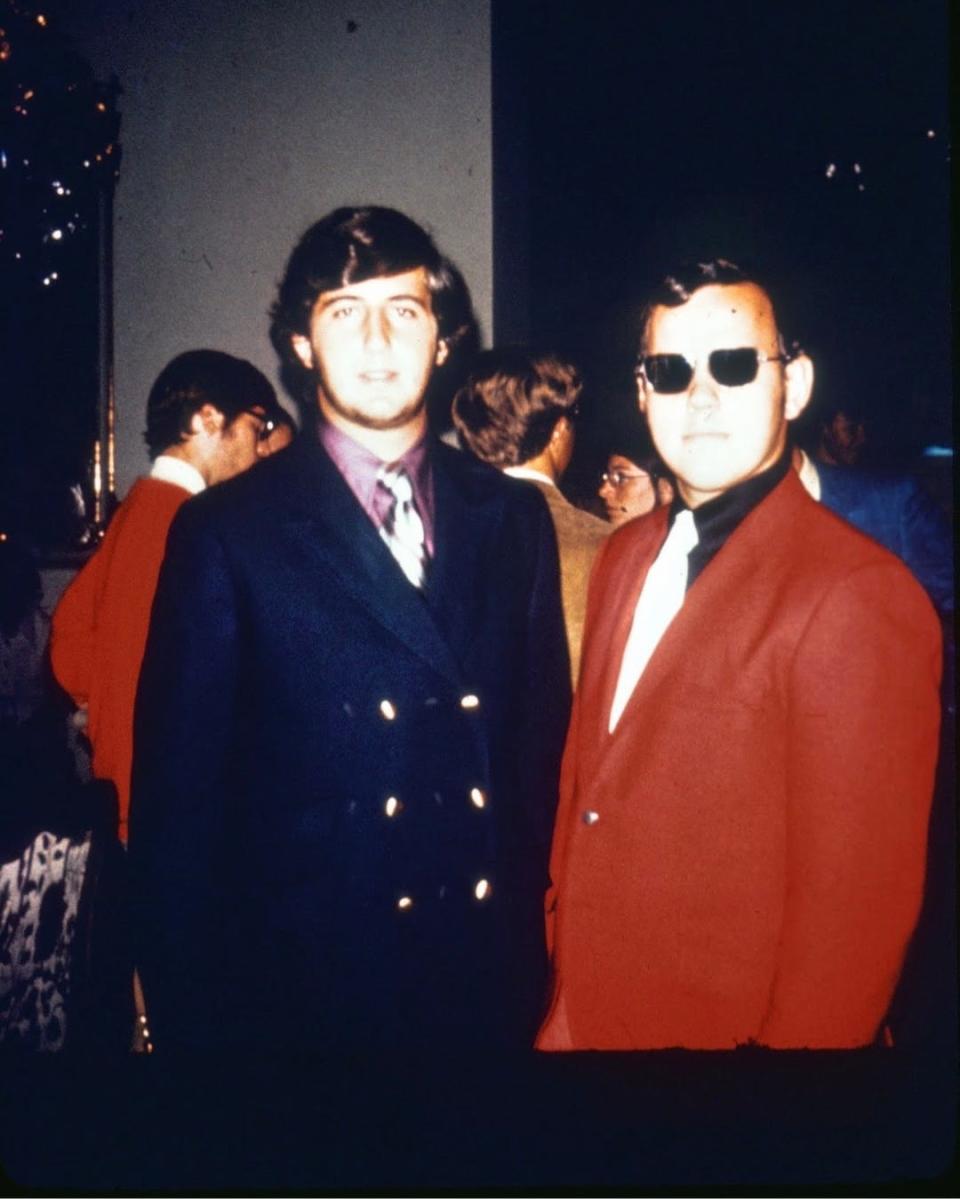

Pete Weber was a student at Notre Dame the first two times he was "fired" — once in radio and once in TV.

His good buddy Mike White, the man Weber credits for giving him his start in radio, also is the man Weber said fired him first.

Sort of.

White was the program director at the cable-access channel. Weber was a lowly paid summer sports reporter. As summer came to a close, Weber had prerecorded a Friday show before he returned to Notre Dame, per usual.

"We had a blonde working there who looked like Chrissy (Snow) from 'Three's Company,' " White said. "Pete did a lip sync with his voice and her reading sports."

He didn't tell anyone. White was amused, but didn't air the segment for fear of losing his own job.

When Weber returned to work the following Monday, White suggested he call it a summer at the station and go back to school.

"He tells me I fired him," White said. "I just told him to take off four days early.

"The broadcast was perfect, though."

The other time Weber was fired was by the local radio station, which Weber and his brother had plans of trying to buy. But that's a story for another time.

Pete Weber vs. nuns

Long before losing his first two jobs, Pete Weber was whacked regularly on his left hand by the nuns at the Catholic schools he attended.

In their eyes, being left-handed like Weber wasn't all right. They forbade him from using his left hand to write.

"They beat it with those rulers with the metal bands at the end," he said.

"It was, 'Peter, the Latin word for left is 'sinister.' Do you wish to be sinister?' I got my hand swatted a lot."

Weber, the prankster with the photographic memory, would get his revenge on one nun who was "a good English teacher who drove me absolutely crazy."

On Feast Day, a day to commemorate the lives of saints, Weber organized everyone in class to bring in fruits and vegetables.

"We brought in potatoes spray-painted black and put toothpicks in them to stand them up like a nun," Weber said. "I think she ultimately had to go off for counseling."

His friends appreciated his sense of humor, though.

The thud, thud, thud of parking cones

Weber did things like transpose the first letter of a person's first and last names on the spot, which he did to his baseball coach, Dick Gillenwater.

"He called him Gick Dillenwater," White said. "So the rest of us started calling him that. We would forget that wasn't his real name.

"He has the ability to see a situation and turn it into something funny, and yet not skip a beat."

Like the time he and Ippolito were at Chicago Bears camp. Weber was in town as a radio journalist. He convinced the Bears that Ippolito — just a Bears fan with a camera — was his photographer.

His radio photographer.

Before they knew it, they were standing next to Walter Payton on a practice field.

On the way home to Galesburg, Weber dozed off in the driver's seat. Ippolito did the same in the passenger seat.

"Then we heard the 'thud, thud, thud' of the orange parking cones because he was running over them," Ippolito said.

"It was quite a day."

'He's just Pete Weber from Galesburg'

That's Pete Weber.

You never know where he's going to take you.

He can seamlessly U-turn a conversation on a dime. Like when he recommended the bison burger, his second-favorite dish, to a lunchmate at Ted's Montana Grill in February.

"Ted Turner, he did something right," Weber said after ordering his favorite dish, Caesar salad with salmon. "I don't know how much subsidy he gets from the government, but he raises bison on ranches in Montana."

Like his father never turned into "Rudy," Pete Weber never turned into Hall of Fame baseball players Stan Musial or Lou Brock. Or three-time MLB All-Star catcher Jim Sundberg, even.

He's not Harry Caray, nor Jack Brickhouse nor Jack Buck.

He's perfectly fine being Pete Weber.

Always has been. Always will be.

"When he comes back to town, he's just Pete Weber from Galesburg," White said.

Weber is a man known for his funny impressions. He's a man who has left an impression most everywhere he has been on most everyone he has met.

He's a man who has left an impression on where he came from, a west-central Illinois railroad town called Galesburg.

Paul Skrbina is a sports enterprise reporter covering the Predators, Titans, Nashville SC, local colleges and local sports for The Tennessean. Reach him at pskrbina@tennessean.com and on the X platform (formerly known as Twitter) @paulskrbina. Follow his work here.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Pete Weber's path to Nashville Predators? Nuns, Notre Dame, baseball