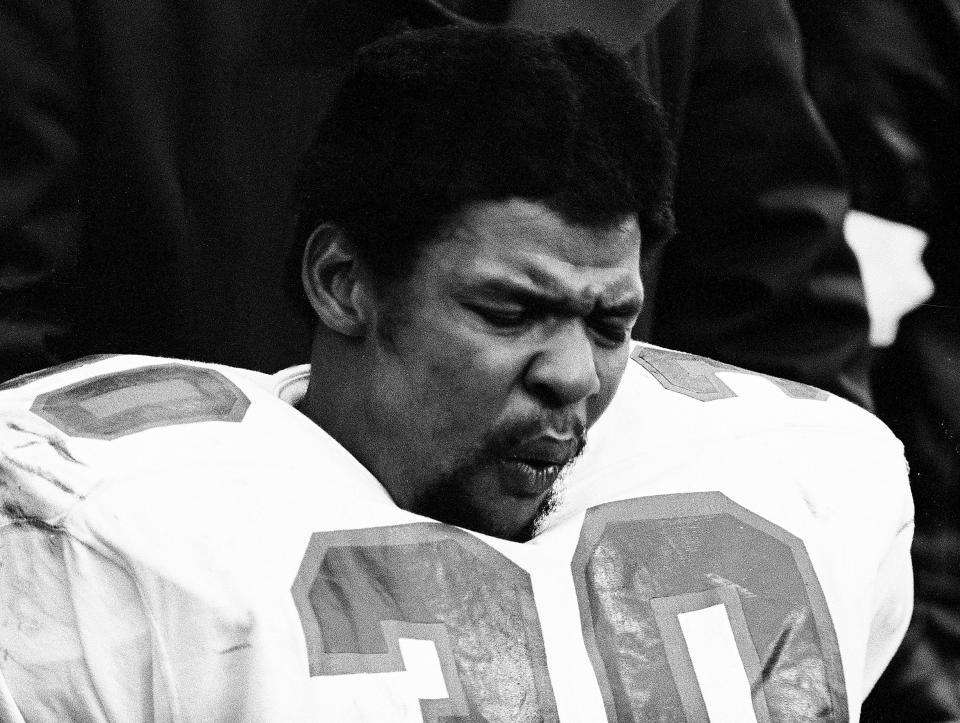

John Harvey was an Austin high school icon, and there won't be another like him | Golden

When a packed house of friends and family gather to honor one of Austin’s greatest athletes at St. James Baptist Church on Friday, they will agree on one thing: Very few high school athletes in Austin came close to the impact John Harvey made at old Anderson High.

Just ask Thomas Henderson, one of the straightest of shooters.

When asked about his late friend, a PVIL and Anderson High Hall of Famer who passed away May 30 at age 74 after a long bout with throat cancer, the Austin-born former Dallas Cowboys linebacker got straight to the point.

More: Cowboys star Trevon Diggs encourages Austin athletes to reach for their own stars | Golden

“I want to talk about the John Harvey the boy, not the man,” Henderson said. “Look, I played with Tony Dorsett. I played against O.J. Simpson and Walter Payton. I had to cover Gregg Pruitt, who was a handful, but I did it. John Harvey is the best athlete I’ve ever been around. Those guys couldn’t touch him.”

Then he added for emphasis:

"And I was no Olive Oyl.”

There is a laundry list of great athletes to come out of the 512, a list that begins with Dick “Night Train” Lane, a Pro Football Hall of Famer and arguably the greatest defensive back in NFL history. We can’t name them all in one sitting, but you have to mention MLB All-Star Don Baylor; Super Bowl champion quarterback Drew Brees; Dustin Runnels, who achieved fame in pro wresting under the name Dusty Rhodes; and PGA greats Ben Crenshaw and Tom Kite, the latter moving here from the Metroplex as an adolescent.

Henderson puts Harvey at the top. As a young kid following around the older guys at Anderson back in the late 1960s, he was in awe.

More: Landmark Longhorn Network will close soon, but it made college sports history | Golden

Long before he became “Hollywood,” an ultra-athletic 220-pound linebacker who won a Super Bowl with the Cowboys and once returned a kickoff for a touchdown before substance abuse problems conspired against a promising career, Henderson was a wide-eyed youngster who just wanted to be in the same space as the best athletes on campus, especially the one he revered the most, Harvey.

Remembering the good times

As they feasted on jerk chicken at Hoover’s Cooking in the days after Harvey's passing, friends who knew him best shared laughs and their best memories of their departed brother. Charles Roberts and Tommy Gregg swapped 50-year-old track stories as if they had happened just last week. Basketball teammate William Ward, who hit the winning shot against Killeen to give the Yellow Jackets their first district basketball title in 1968, spoke of the camaraderie shared by teenage boys growing up in the late 1960s a part of the Black population still in search of a slice of the elusive American dream.

More: Texas athletics wins third Directors' Cup in four years as nation's top college program

Longtime friend Dan Napier gushed while remembering the day at Gregory Gym when Harvey walked in off the streets in blue jeans and Chuck Taylors and threw down a tomahawk dunk without even warming up.

Hoover's owner Hoover Alexander treated the table to chili burgers as a tribute to Harvey and the old Harlem Theater. The legendary East Austin establishment, on 12th and Salina streets, served moviegoers for nearly 40 years before burning to the ground in 1973.

Remembering Harvey, the track man

There are so many stories of Harvey’s legend that you might think he owned a blue ox named Babe, but these weren’t tall tales. Harvey was an athletic god in a 6-foot-2, 180-pound frame.

Eight years before Lampasas star Johnny “Lam” Jones made up a seemingly insurmountable lead to anchor a 400-meter relay win at the 1976 UIL state track meet, Harvey cemented his local legend at the Class 4A meet when he ran down runners from Corpus Christi Moody and favored Spring Branch Memorial to bring home the mile relay crown, this after coach Granville Ewing moved the junior he nicknamed “Big Hoss” from third leg to anchor.

With a 20-yard gap that has grown over the years depending on who tells it, Harvey, once described by former Texas coach Mike Campbell as “a one-man track team,” was facing an insurmountable deficit after a bobbled handoff with Cornelius Shoaf.

Harvey’s split was clocked between 45.5 and 45.8, which was blistering at that time. He crossed the tape in 3:15.8, leaving his opponents in the Central Texas dust.

“I looked up, and those other boys were gone,” teammate Roberts said. “Then John shifted gears. He was flying. Dave Martin was the anchor for Spring Branch, and he could go, but John ran him and the other guy down.”

More: Texas basketball will face North Carolina State in SEC-ACC Challenge

The win tasted especially sweet at a time when racism was openly practiced, despite some strides being made during the civil rights movement. The Yellow Jackets, no strangers to mistreatment as the only all-Black high school in Austin, were subjected to a horrible act of hatred weeks earlier in Laredo.

“One of the Spring Branch guys actually spit on Cornelius Shoaf before the mile relay at the Border Olympics,” said Gregg, the first leg runner. “We all were livid, but (Ewing) told us to just to wait because we would get them again. As fate would have it, we met them again at the state meet. The rest is history.”

More: Texas football lands commitment from 3-star CB Caleb Chester after Lambo-filled visit

The birth of an Austin legend

Lenora Harvey lived in the Booker T. Washington housing project with her daughter, Peggy, and sons, Carl and John, the youngest, born in 1950. Austin wasn’t the growing metropolis it is today. In the 20 years after World War II, the population actually doubled to more than 200,000. Even with the boom in growth, Texas’ most laid-back bedroom community was largely segregated. The Jim Crow era would end in 1965, but Texas was in no hurry as far as progress was concerned.

A single mom, Lenora paid the bills as a beautician, working from a shop connected to the side of their East Austin home. The boys were active in sports, and young John was popular among his classmates at Rosewood Elementary, though the incredible athleticism he would display later in his childhood wasn’t immediately evident.

“Up until about sixth grade, John was clumsy,” recalled Carl Harvey, his younger brother. “But when he hit the seventh grade, his talent came alive all of a sudden. He took to sports and was great at everything he played. You could tell that he was going to be special someday.”

By the time he reached Anderson, Harvey had quickly become the talk of the neighborhood. He was part of an era when an athlete played football in the fall, basketball in the spring and baseball in the summer while running track in between.

Whatever sport he played, the kid was in demand.

“It was funny because the other coaches had to wait for him,” Roberts said. “The basketball coaches had to wait until football was over. Track had to wait until basketball was over. He was great in baseball too. Once he joined your team, it became a great team.”

Meeting DKR

Track and basketball exploits aside, Harvey was also one of the best football players in the area, and the most prominent coach in the state had taken notice.

After coach Raymond Timmons moved him from flanker to running back his senior year, Harvey rushed for 883 yards in 10 games and averaged 5.8 yards per carry. Defending state champion Reagan handled the Yellow Jackets 34-6 that season, but Harvey, voted by coaches as the district’s best running back, ran for 172 yards in a losing effort.

On the afternoon of Friday, Feb. 14, 1969, Texas football coach Darrell Royal signed the 19-year-old Harvey to what was called at the time a pre-enrollment agreement with the school. Harvey was going through a rough spell as he had broken his foot in hoops.

Royal grabbed a pen and signed Harvey’s cast. He's the first Black athlete Royal signed.

At the time, hopes were high for the local product, who talked of being more than just a football player on the Forty Acres. Horns basketball coach Leon Black had an eye on him, as did track coach Jack Patterson. While his football exploits got him the most headlines, he also averaged 19.1 points his senior year before the hairline fracture ended his season. He ran a 22.4 in the 220-yard dash, ran 48 flat in the 400, went 23-4 in the long jump and anchored the Yellow Jackets’ gold-medal effort in the mile relay at the state meet in 1968.

“If I can play three sports and keep up with my classwork,” he would, Harvey told the Statesman the following Saturday. "I want to make something of myself at Texas.”

As it turns out, Harvey did not qualify academically. He enrolled at Tyler Junior College, where he earned NJCAA All-America honors in 1970. After two years at TJC, he spent a season at UT-Arlington. Fifty-plus years before NIL, his buddies all laughed when he pulled up to the old neighborhood in a brand new Cadillac. It was a huge upgrade from the clunky Dodge DeSoto he drove around town with his buddies in tow.

“It was different than that DeSoto, which had its wheels pointed in,” Ward said. “It was knock-kneed, but it got us from Point A to Point B.”

Off to Canada

After college, Harvey signed with the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League and finished second in league MVP voting after rushing for 1,024 yards in 1973. He played three years up north and two seasons in the short-lived World Football League. The Los Angeles Rams took him in the seventh round of the 1974 draft, but he didn’t stick with the organization.

Not unlike many athletes in the era — his friend Henderson was one — Harvey battled some personal demons in adulthood. This issue wasn’t helped by a voracious smoking habit. Friends say he could go easily go through three to four packs a day.

“We used to get into it all the time about those cigarettes,” Carl Harvey said. “He wouldn’t put them down.”

After his playing days ended, Harvey worked for the city for some time, and during his toughest times, the father of three clung to family and friends. Carl remembers that Sunday night in October 1983 when Harvey preached his first sermon at St. James.

“I looked up, and there was John, walking down the aisle toward me,” he said. “He gave his life to the Lord that night.”

The decade-plus battle with cancer led to nearly 50 treatments at MD Anderson, but he and wife Barbara remained positive. Before their health declined, they served as ushers at Turning Point Bible Fellowship, the church Carl founded nearly 28 years ago.

His brother made his mark on this city. Good athletes are often made, but the special ones are usually born. Austin won’t see another like him.

“They talk about Jim Brown and Muhammad Ali, but John Harvey was a giant in my world,” Henderson said. “He was my childhood idol.”

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Old Anderson High School's John Harvey was a genuine Austin legend