Landmark Longhorn Network will close soon, but it made college sports history | Golden

While the Texas baseball team was busy finishing up its regular-season finale against Kansas on Saturday, a door quietly closed in the broadcasting world.

It was the Longhorn Network’s final traditional team broadcast, and longtime booth partners Keith Moreland and Greg Swindell bid adieu to Longhorn Nation. They've done in the neighborhood of 400 games at UFCU Disch-Falk Field, and the last one, while sad, brought a historic end in sports broadcasting.

LHN’s coverage was a welcome presence to the households of Longhorns fans who lived out of state or otherwise couldn’t get to the games.

The network was an audacious undertaking that lined Texas’ pockets through a massive deal with ESPN that was not only the first of its kind — a broadcasting giant partnering with a single university — but one that would signal a coming change in the high-dollar worlds of broadcasting and college football.

It was the first of its kind and likely the last.

How it all started

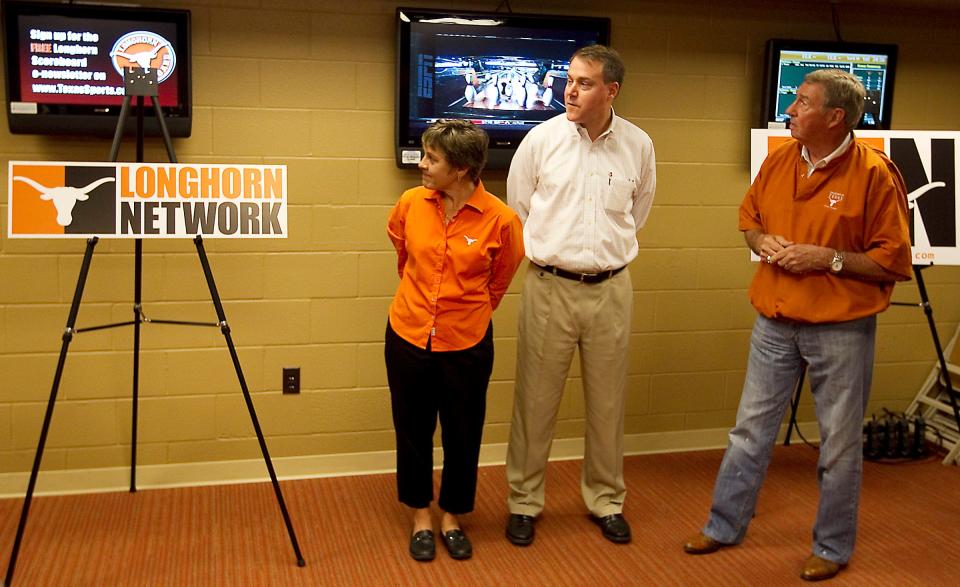

The challenges were too numerous to mention in entirety, but the early conversations between legendary Texas athletic director DeLoss Dodds, his executive senior athletic director/external communications guru Chris Plonsky and UT President Bill Powers mostly centered on whether this network would be well-received.

An investment fund had reached out to Dodds in the early 2000s to inquire about his interest in establishing a network similar to what MLB’s New York Yankees were doing with the YES Network since the Horns had ownership of their third-tier sports media library. Word also had gotten out that Big Ten Commissioner Jim Delany was working on a conference network as a means of creating revenue outside of the lucrative football/basketball deals the league had with the major network.

More: Texas ex Adonai Mitchell will use his NFL draft slight to become a Colts star | Golden

In the spring of 2007, Dodds and Plonsky met in Dallas with the league’s biggest power brokers at the time — Big 12 Commissioner Kevin Weiberg, Oklahoma athletic director Joe Castiglione, Texas A&M AD Bill Byrne and Nebraska AD Tom Osborne —to discuss the feasibility of a Big 12 Network.

"We were all looking for a way to increase revenue and build the conference brand," Dodds said. "We wanted to strengthen our position in the world of college athletics. The idea of a network had been talked about for some time back then."

Weiberg had been a stabilizing force in serving as a sports version of a marriage counselor with the job of stabilizing the relationship between schools from the Big Eight and Southwest Conference that merged to form a new league in 1994. After he replaced the league’s first commissioner, Steve Hatchell, league revenues reportedly nearly doubled in his first year (1998). Nine years into his tenure, the idea of a league network brought the possibility of even more revenue, but the schools, including Texas, voted against it.

Weiberg, obviously frustrated that he couldn’t persuade the most powerful schools in the league that a Big 12 Network would work, left for the Big Ten, where he helped launch its new network.

Dodds later approached Byrne with the idea of the state’s two most powerful athletic departments partnering to form what was being loosely referred to as the Lone Star Network.

Dodds would say in later years that Byrne didn’t show as much enthusiasm for such a massive undertaking, though. The Aggie boss and then-Missouri coach Gary Pinkel made no secret of their disgust with ESPN's plan to show high school football games on the network as a definite point of contention.

More: Texas Longhorns baseball beats Kansas at UFCU Disch-Falk Field on Friday. See the photos

“I disagree with their stance, as do many of my colleagues across the country,” Byrne wrote on Texas A&M’s website. “We anticipate that ESPN will continue to push the envelope with the Longhorn Network, regardless of Texas A&M’s conference affiliation.”

Yes, conference realignment was in the air, and the Big 12 was changed forever. Nebraska left for the Big Ten in 2010. Colorado headed west to the Pac-12 in 2011. The Aggies and Missouri began play in the SEC a year later.

Depending on whom you ask, the Longhorn Network played a prominent role in the splinter because it was a constant reminder of Texas’ political power. UT was also seriously considering leaving the Big 12. In 2010, wild reports were circulating that an agreement with the Pac-12 had been reached to add Texas, Texas Tech, Oklahoma and Oklahoma State.

After spending a couple of days with Delany — whom Plonsky knew through working in sports communication for Big East Commissioner Dave Gavitt, whose savvy negotiations with ESPN turned the Big East into a national basketball phenomenon — Plonsky returned to Austin and headed straight to Dodds’ office.

They were on the same page. Texas would go it alone.

Dodds had a question for her: “Would you watch a Northwestern-Illinois softball game on TV?”

“Probably not,” she said.

“But you would watch anything Texas, wouldn’t you?”

“Damn right I would,” she said without hesitation.

A partner arrives from Bristol

Dodds and Plonsky soon arrived at the same conclusion. This wasn’t a time to wait around for a network or cable system to reach out when there was work to be done. The Big 12 deal didn’t feel right, and there was a certain freedom that came with sole ownership.

“We were looking at first at doing a conference network, but when you do a conference network, you’re getting only one-eighth or one-tenth of the deal, so you’re part of a group,” Dodds said. “We decided we wanted something that we could own that could be about us.”

Fox Sports was the first to contact Texas. In June 2010, the network proposed a $3 million annual payout somewhere between $60 million and $75 million. It would presumably flip one of its many regional channels into a Texas Longhorn network. But before the two sides could come to a formal agreement, ESPN executive Burke Magnus placed a call to Plonsky.

“Don’t do the Fox deal,” he said, requesting a meeting.

“Where the hell have you been?” Plonsky asked with the perfect blend of feistiness and affection. She was on her way to the U.S. Open golf tournament and had been waiting weeks for that call.

She called Dodds.

“What do you think, CP?” he asked.

“It’s ESPN,” she said. “We have to listen.”

The bottomless ABC/Disney coffers are unlike any others in the sports world, so when Magnus and fellow ESPN bigwig John Skipper met with the Texas contingent of Dodds, Plonsky, Powers and general counsel Patti Ohlendorf, history was in the making.

Texas had partnered with Host Communications — later sold to IMG — because Dodds and Plonsky believed executive Tom Stultz would do a great job courting potential corporate partners. He had already brokered meetings with Comcast, Time Warner, DirecTV and Dish2, but when it became obvious Texas might go it alone, Fox and ESPN entered the arena.

Stultz believes ESPN signed on because the idea of Texas and other football blue bloods establishing their own networks would prove problematic down the line.

The Mouse offered Bevo a $300 million lottery ticket — $15 million annually over 20 years — and would cover the cost of a studio just north of campus, on-air talent and producer Ande Wall, who capably put together a talented group of content producers and behind-the-scenes staffers.

“That was above and beyond any rights fees that we were paying,” Stultz said. “And, of course, DeLoss being DeLoss, he tweaked some percentages and negotiated a really good deal with us.”

And a great deal for Texas, to the tune of an 82.5% to 17.5% split of revenue with Host on top of the $15 million it would get each year from Bristol.

The Longhorn Network launched on Aug. 26, 2011, but since the deal with ESPN wasn’t due to take effect until Sept. 1, only Verizon Fios subscribers were in play to access the Texas-Rice football opener — bad news in Central Texas, which didn’t carry it. Somehow, a bootleg signal made its way online, and many happily watched Texas’ 34-9 win.

Eventually, ESPN ironed out workable deals with cable and satellite systems, and LHN became readily available nationally, which was a boon for Longhorn Nation and a huge recruiting tool, especially for families of out-of-state players in all sports.

Coaches could now tell recruits that some of their games would be shown in their home living rooms at the click of a button.

The face of the franchise

Mack Brown was the perfect person to push as the face of this new venture. Easily the most charismatic personality on campus since Darrell Royal and Abe Lemons, Brown was the perfect face for this brave new venture.

For this to work, it had to be football-heavy, and Brown was the guy to do it.

Problem was, Mack was football depressed. He admittedly spent most of the 2010 season coming to grips with the unbeaten Horns losing to Alabama in the 2009 BCS national championship game and how it all went down with All-America quarterback Colt McCoy being lost to a shoulder injury on his team’s first series.

So deep was Brown’s heartbreak that the Colt-less Horns endured a 5-7 nightmare in 2010, easily the worst of his 16 seasons.

The Horns were planning a 2011 rebound when Brown received word from the tower that the Longhorn Network was coming. He met with longtime senior associate AD John Bianco to discuss how their once seamless football routine would be affected.

If you thought Brown busy pre-LHN, his added duties turned a full plate into an overstuffed platter. He had "Longhorn Rewind" on Monday after meeting with the media and doing a Big 12 show. The coordinators did studio interviews Tuesday. "Longhorn Weekly" was a Wednesday TV/radio simulcast. He was back for a studio show Thursday. And that was in addition to "Longhorn GameDay" and game day obligations.

The fans lapped it up, but Brown admits, amid all the new network stuff, he was challenged. Some on campus saw the work Brown was putting in away from the field and started calling it the Long Hours Network.

“It did add a lot of work,” Brown said. “I thought it was wonderful. It gave us a tremendous amount of publicity. But then we found out that all of our opponents had the Longhorn Network and were watching our practices.”

It's something current baseball coach David Pierce can co-sign.

"I really feel like we're the most scouted team in the country, year in and year out, and now that a lot of the video is catching up, people are kind of equalizing that," Pierce said. "But for many years, every one of our opponents had DVR and recorded everything we'd do. Then the guys in the booth have a job to do so we're in a bunt coverage and they expand the field and they show everything we do to give the best coverage, but sometimes that exposure can hurt us a little bit. But it's been awesome; it really has. I'm going to miss them."

At one point later in LHN's first season, Brown's Horns were hit with the injury bug at running back — Fozzy Whittaker blew out his knee in a loss at Missouri — and Brown had to revamp his practice drills to hide the lack of numbers at such a key position from prying eyes.

The Brown/LHN dynamic was a working relationship that was in obvious need of a happy medium, which eventually happened but not without some tense moments.

Days after the Missouri loss, Brown planned to address an issue involving his reporting of injuries to the media and wanted to discuss it off the record, a common practice in our business. In those instances, writers usually don’t record conversations and broadcasters also turn off their cameras. That day, all but one reporter complied with shuttering their recording devices — except for a lone LHN cameraman, who stood to Brown’s left with his video camera resting on his shoulder, the lens aimed at Brown.

More: Mike Elko brings accountability to Texas A&M, which made right hire at right time | Bohls

“Is that thing off?” Brown asked before getting to the issue at hand.

The cameraman said nothing but proudly tapped the large LHN logo on his golf shirt as if the off-the-record protocol didn't apply to him.

“I need you to turn the camera off, not change your shirt,” Brown said.

Reporters chuckled, but the message was sent. There was still a pecking order, and Texas’ new $300 million plaything did not rank above the most recognizable face on campus.

Brown’s mug was the most visible in those days, but the network provided a platform for other sports to gain some needed exposure. Jerritt Elliott built volleyball into a national power — the Horns won the first of two national championships under Elliott in 2012 — while previously underexposed sports found their niche as well.

“Who would have ever thought we’d get 16 hours a day of Texas Relays?” Plonsky quipped. “Who could have imagined getting 16 hours of Texas Relays coverage over a weekend. We would have never believed we would get so much for our university, our kids and our coaches. (Dodds and Stultz) saw around the corner with where things were going. They’re so much alike. This doesn’t happen without them.”

It also doesn’t happen without Plonsky, who was Dodds’ constant partner — his corporate eyes and ears — when he wasn’t available.

ESPN’s reach gave LHN access to some excellent broadcast journalists. Samatha (Steele) Ponder was the first Longhorn Network correspondent. Lowell Galindo and Alex Loeb doubled as studio hosts and play-by-play talent. Kaylee Hartung and Jane Slater followed Ponder, later parlaying their LHN/ESPN gigs into reporting jobs — Hartung at CNN, ABC News and the "Today" show and Slater at the NFL Network.

Slater, a Texas grad, showed up in time for the Charlie Strong era of football in 2014, and while the wins weren’t there on the field, the experience left an indelible mark on her career.

“I don’t think I would be at the NFL Network if not for the experience I had at Longhorn Network,” Slater said. “It was always a unique experience to cover my alma mater and have a desk looking out to the Tower.”

Wall was there from day one, moving from Bristol to Austin with a brief stop in L.A. to work the ESPNs in between. After producing "Sports Nation" after arriving there in 2006, Wall built a staff that was proficient at multitasking and producing quality content.

“One of our priorities was to develop talent in front of the cameras and behind the camera,” Wall said. “We took that seriously. It was a permanent spot for some and a training ground for others.”

Loeb started as a part-timer in 2012 and earned a full-time gig in 2015.

“It was like a family in a number of ways,” Loeb said. “We worked with a really small group at LHN, and we worked so closely with the university. … That was like another family. So to do this for a decade and have all these unbelievable stories to tell and bring these kids in to do long-form interviews and hear their stories was great. It’s been amazing.”

ESPN also leveraged the popularity of legendary alumni such as Sanya Richards, Cat Osterman, Fran Harris, Andrea Lloyd, Lance Blanks, Vince Young, Michael Griffin and others to boost content. They served as commentators and analysts, adding some present-day flavor to game days.

Griffin, a starting safety on the 2005 national champs, had played 10 seasons in the NFL — nine with Tennessee — before retiring in 2016. During a visit to Texas Pro Day at the practice bubble, he did a segment with Galindo, LHN's anchor. When an opening was created for game-day in-stadium analysis, Bianco recommended the former Bowie High star to Wall.

“When I got the call from them in 2018, I was in Tennessee doing a coaching internship with the Titans,” Griffin said. “It was coach (Mike) Vrabel’s first year. I remember telling them I was going back to Austin to work with the Longhorn Network.”

Former football coach Tom Herman affectionately called it the History Channel, a great moniker given the endless stream of old feel-good footage that found its way to our TV screens.

The network gave us a steady diet of Texas’ 2005 national title win over USC and the 1969 win over Arkansas on the way to that national title, in addition to some great in-house documentaries like "05" — a chronicling of the aforementioned Rose Bowl — and some heartwarming stories, like volleyball legend Asjia O’Neal chronicling the health issues she overcame en route to a pair of national championships.

It was a proving ground for young talent that ended up on larger stages and played a role in the changing face of this league. A case can also be made that it might have saved the Big 12.

How we will remember the LHN

It was never a ratings grabber. ESPN reportedly lost $48 million to the Longhorn Network over its first five years in addition to the $75 million it paid out per its contract, but no one was turning down that kind of money.

It was a welcome cash cow on a campus of Longhorns.

Timing was everything and Dodds was prescient in playing his cards in such smart fashion. ESPN didn’t make any money on the network but in a sense might have saved itself millions after Texas decided to stay in the league when other conferences were circling.

“Had Texas left the Big 12 at that time and gone to any other conference or gone independent, then ESPN would have had a big hole in their coverage in the middle of the country,” Stultz said. “I think they would say that it was worth what they paid for the Longhorn Network in order to keep the Big 12 together because it gave them content in states with a lot of cable households that they needed.”

A new-look LHN

The good news is it won’t be entirely going away.

The last month will be a revisiting of the network’s top moments and surely a few dozen replays of VY running into the end zone in Pasadena. Also, senior athletic director Drew Martin will launch an app July 1 that will make globs of LHN content— coaches shows, profiles, documentaries — available on demand.

The physical LHN will be no more, but the app will keep that good content alive in perpetuity.

"It's been a win for Texas," UT athletic director Chris Del Conte said. "The way it enhanced the brand was amazing. Anytime a university with its own network with content of that quality, it's a real testament to the leadership of DeLoss Dodds and Chris Plonsky."

It was some undertaking. Brave, bold and historic.

“Obviously, it was ahead of its time,” Brown said. “And what I thought were positives and concerns for the football team, it was great for the university and the other programs that couldn’t be on TV. It was worth the money. It was a challenging time but a fun time.”

Thanks, LHN. Well done.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Golden: Texas' Longhorn Network changed landscape of college sports