What the latest episode in the Boeing safety saga means for ordinary travellers

Beleaguered US manufacturer Boeing has agreed to plead guilty to a criminal fraud charge relating to the development of its short-haul 737 Max jet, which suffered two crashes in which 346 people died.

After the disasters, in Indonesia in 2018 and Ethiopia in 2019, the US Justice Department charged Boeing with conspiracy to defraud regulators. The firm deceived the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) about new flight control software that was responsible for both accidents, the DoJ alleged.

But in 2021 the DoJ agreed not to prosecute Boeing if the company agreed to pay a $2.5 billion settlement, including a $244 million fine, and to accept close independent monitoring of safety standards for three years. Anxious to avoid public court hearings in which senior executives would have been cross-examined about the introduction of the flight control system, Boeing accepted.

Just days before the three-year probationary period was due to end in January this year, a door panel in an Alaska Airlines Boeing 737 Max blew out shortly after it took off from Portland, Oregon. Remarkably, the plane made a successful emergency landing and none of the 171 passengers and six crew on board was injured – but the accident called into question Boeing’s progress on improving safety. The door had not been bolted into the fuselage correctly after routine maintenance.

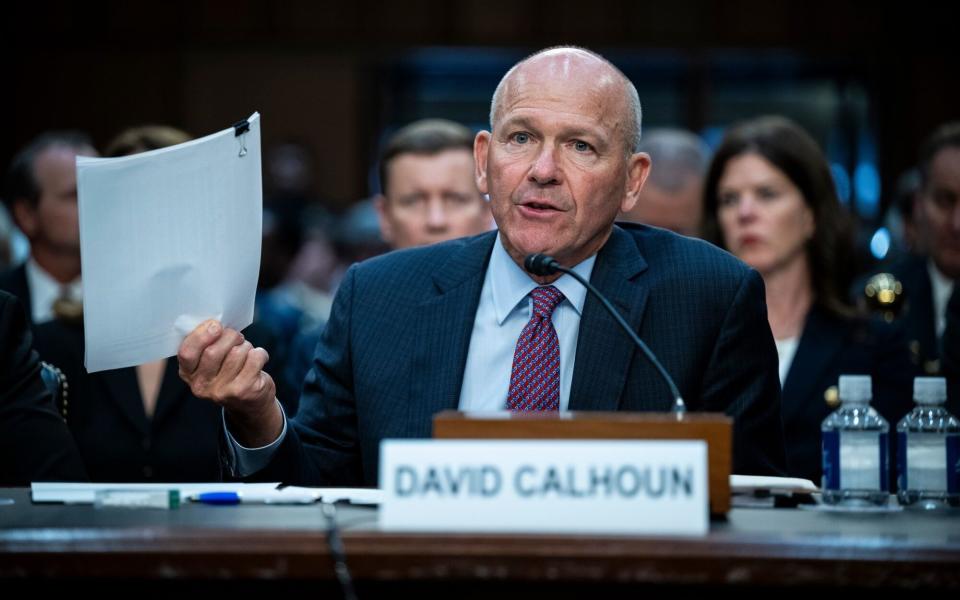

In May, the DoJ found Boeing had violated the terms of the 2021 agreement, re-opening the possibility of a criminal trial. Boeing initially pushed back but earlier this week settled with the DoJ. It agreed to plead guilty to criminal fraud, to pay an additional $244 million fine, to invest at least $455 million over the next three years to strengthen its safety and compliance programmes, and to submit to further intensive monitoring of safety standards. It will also be subject to a period of court-supervised probation.

What does the compromise deal mean for Boeing and for passengers?

The deal has not been formally approved. A US judge needs to rubber stamp it at a hearing due later this month. Families of the victims of the two crashes say they will oppose it in court. They argue a criminal trial is the only way to discover what Boeing executives knew about the deception of FAA regulators.

Paul Cassell, a lawyer representing some of the victims’ families, called on the judge assessing the deal, Reed O’Connor of the US District Court in Fort Worth, Texas, to reject “this sweetheart deal”. The court should “set the matter for a public trial, so that all the facts surrounding the case will be aired in a fair and open forum before a jury”.

If Judge O’Connor rejects the compromise arrangement, Boeing and the Justice Department could try to negotiate a new agreement or go to trial. If he approves the deal, Boeing will be relieved it will have avoided its day in court for a second time but it will be a corporate felon. That will be a staggering blow to the reputation of the 100-year-old firm whose products were once so safe and reliable that passengers’ mantra was: If it ain’t Boeing, I ain’t going.

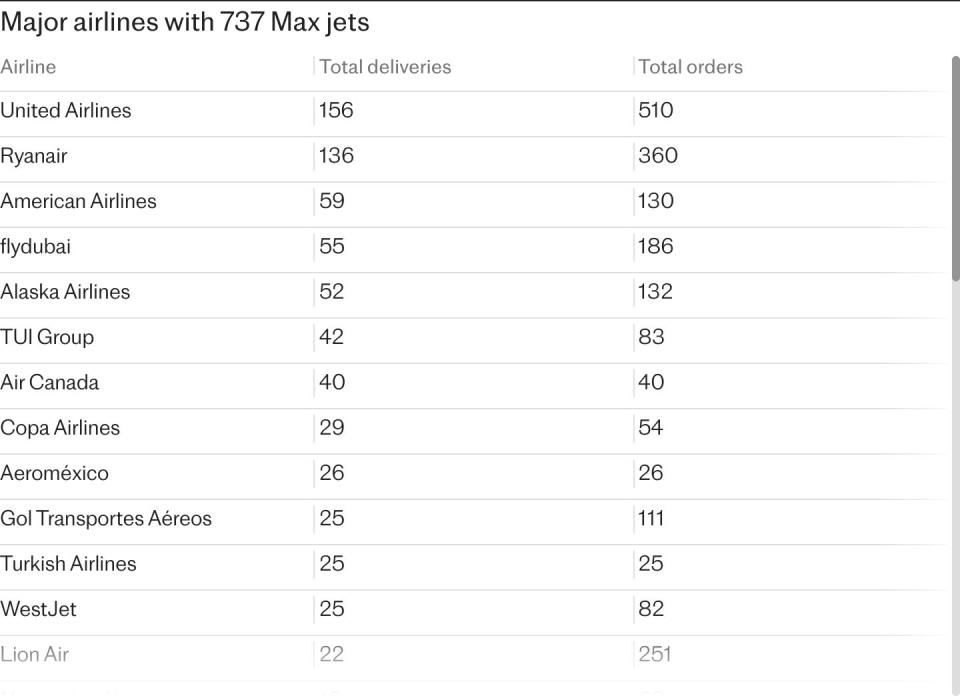

It will also strengthen the hand of victims’ families who have not settled their pending civil lawsuits against the company. Boeing has agreed to pay $500 million to a victims’ fund but many families dismiss that sum as woefully inadequate. Some passengers will continue to avoid Boeing jets, especially the Max – a model that features in the fleets of several European carriers including Ryanair, Turkish Airlines, Tui and Norwegian.

However, that is about as bad as it is likely to get for the maker of almost half of the world’s commercial airliners for now, as the firm’s share price indicates. It ended at $185.84 on Monday after the guilty plea was announced, up $1.01 from the close on Friday.

Aviation analysts say that although the US government usually bans firms with a criminal record from bidding for federal contracts, Boeing’s defence contracts, its work for the Nasa space programme, and its role as builder and operator of Air Force One, the presidential flight, are likely to be unaffected. The US Air Force cited “compelling national interest” in letting Boeing continue competing for contracts after the company paid a $615 million fine in 2006 to settle criminal and civil charges unrelated to the Max. One third of Boeing’s revenue last year came from US government contracts.

Demand for passenger jets is at an historic high as the appetite for air travel post-pandemic continues to grow. In 2022 global air passenger demand grew by 64 per cent, compared with the previous year. It is forecast to grow by another 9.8 per cent by the end of this year. From budget operator Ryanair, whose fleet is based on the short-haul Boeing 737, to Emirates, which had expected to be flying the long-haul 777X by now, airlines need a strong Boeing.

There is, however, one legal cloud on the horizon for the firm. This week’s plea deal does not cover the Alaska Airlines incident in January. The DoJ has opened a separate investigation into that near-disaster. America’s National Transportation Safety Board and the FAA are also investigating.

Boeing said in a statement that it was putting together “a comprehensive action plan to strengthen safety and quality, and build the confidence of our customers and their passengers. We are squarely focused on taking significant, demonstrated action with transparency at every turn.”

This article was first published in January 2024 and has been revised and updated.