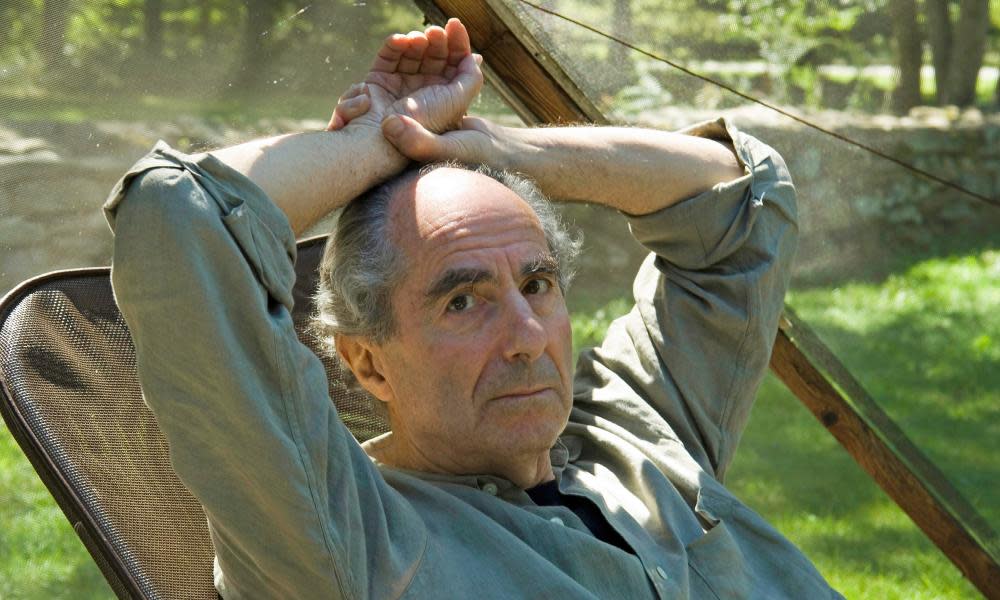

Philip Roth obituary

“I write fiction,” warned Philip Roth, “and I’m told it’s autobiography. I write autobiography and I’m told it’s fiction, so since I’m so dim and they’re so smart, let them decide.” That half-defensive, angry note and a lifetime as a novelist crafting multiple “fake biographies”, gave Roth, who has died aged 85, an enigmatic status for tidy-minded critics. He won intense respect from the moment in the 1960s when he joined Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud in a Jewish troika at the centre of American literature. But there remained doubts, demands for clarification, as though he had not been writing literature after all, but committing a long, strained, perhaps not wholly candid act of self-revelation which merited the critics’ distrust.

Roth’s first book, Goodbye, Columbus (1959), sold a more than respectable 12,000 copies in hardback and received the National Book award. The big one – the Nobel prize in literature – eluded him, but there can be few American literary careers so richly laurelled, early and late. He was a bestselling writer only once in his career, when Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) sold 420,000 copies in the first 10 weeks after publication.

From his earliest work, Roth’s Jewish readers were uneasy with his ironic view of Jewish life. Roth delighted in every nuance and absurdity of Jewish life in America, but his defiantly secular sensibility was without piety or reverence. When asked about his religious beliefs in 2006, Roth told the radio interviewer Terry Gross that he had “no taste for delusion” nor any need for spiritual consolation. The Jewish community saw Roth as a wisenheimer – a sharp-tongued young man who had turned his back upon the religion of his fathers.

Heavyweight critics agreed. Robert Alter saw an element of “uncontrolled rage” against women and Jewish parents in Roth’s early books. Irving Howe argued that Roth lacked Tolstoyan amplitude because his books come out of a “thin personal culture”. Alfred Kazin wrote that Roth seemingly had escaped from his Jewishness altogether.

Repeatedly denying self-hatred or any wish to reject his Jewishness, he wrote: “I have never really tried, through my work or directly in my life, to sever all that binds me to the world I came out of.” But his “really” carried more than a hint of reservation in the midst of an uncomfortable profession of faith. “I was brought up in a Jewish neighborhood,” he remarked, “and never saw a skullcap, a beard, sidelocks – ever, ever, ever – because the mission was to live here, not there. There was no there. If you asked your grandmother where she came from, she’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it. I forgot already.’”

The publication of his short story Defender of the Faith in 1959 was greeted with a storm of criticism. Rabbis accused Roth of Jewish “self-hatred”. He appeared before a hostile audience at Yeshiva University in 1962. The experience left the resilient young Roth unrepentant. He wrote of this experience with high comic delight in Portnoy’s Complaint.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, he was the son of Bessie (nee Finkel) and Herman Roth, who were themselves the children of Yiddish-speaking immigrants from eastern Europe. His father worked as an agent and later office manager for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Philip remembered hearing as a small child the voices of Hitler and Father Charles Coughlin, the Roman Catholic priest whose sermons denouncing communism commanded a large nationwide radio audience. The Roth family listened on the radio to the renomination speeches of Franklin D Roosevelt. “My entire clan ... were devout New Deal Democrats,” he wrote. They were proud citizens of Newark, but lived in an intensely Jewish world.

In two volumes which he disclaimed as autobiography, The Facts (1988) and Patrimony (1991), and in several novels Roth wrote lovingly of his childhood, and of the Newark world of his parents. At the end of The Facts, Roth introduces his familiar alter-ego, Zuckerman, who casts doubts on the silences and evasions of the self-portrait. Zuckerman complains about the “decorous” way Roth talks about himself, and wonders why, at 55, Roth has begun to make his origins look “like a serene, desirable, pastoral haven”.

Tall, curly-haired Phil (as he was known in the family) was passionate about baseball. He regularly attended minor league baseball games at Ruppert Stadium in Newark, and devoted The Great American Novel (1973) to the mythologies of baseball set against the harsher realities of communist subversion and anti-communism. He was a supporter of the Brooklyn Dodgers. At Weequahic high school he had a circle of loyal friends who cherished his bristling intelligence and delighted in his caustic sense of humour. His family stories, recounted in flamboyant mimicry of relations and neighbours, turned family life into comic soap-opera.

While an undergraduate at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, Roth joined a Jewish fraternity, played Happy in a student production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, started a literary magazine, and wrote sensitive stories, “mournful little things”, he later felt, “about sensitive children, sensitive adolescents, and sensitive young men crushed by coarse life.” Wrapped in the seriousness of American literary culture in the post-war period, he graduated with great distinction in 1954. Throughout most of his life he held academic appointments at American universities, beginning at the University of Chicago, where he was an instructor in English for two years from 1956. The experiences – erotic and intellectual – of a writer on campus remained a shaping presence in Roth’s early fiction.

He took a master’s degree at the University of Chicago, where he had a rich exposure to Joyce and Kafka. The writer and critic Ted Solotaroff recalls Roth at Chicago as “aggressive, aloof, moody [and] worldly”. He was drafted by the US army, but a back injury suffered during basic training secured a medical discharge, and he returned to the university’s PhD programme. Living in a tiny apartment on the south side of Chicago, Roth wrote some of the century’s most widely reprinted short stories. Collected in Goodbye, Columbus, his stories were praised for his “ferociously exact” and ironic recording of family life in Jewish America. Roth brought a satirical focus on a new world of prosperity opening up for Jews in the suburbs in the 1950s.

He married Maggie Michaelson in 1959. When he heard nearly a decade later of her death in an automobile accident, Roth’s strongest emotion was relief and surprise: “You’re dead and I didn’t have to do it.” All the tools that he had honed for success in the world were as nothing before what he called his wife’s “flabbergasting boldness” and “masterly pitilessness”.

The two novels he wrote during that marriage, Letting Go (1962) and When She Was Good (1967), were serious-minded “literary” explorations of what lay behind the disastrous relationship. He returned to his life with Michaelson in My Life As a Man (1974) and The Facts. Women who knew Roth well felt that they were continually on trial. Despite his fabled charm and conversational gifts, Roth’s domestic routines were rigid. He had an obsessive need to retain personal autonomy and secrecy, and needed an exit strategy from every commitment.

Roth was not at all sure if long realist novels made sense, at least for someone with his temperament and comic gifts. In other ways it was a false direction, lacking the immense colour and élan of his satirical vein. “There’s not a single Jew in it,” he remarked to Solotaroff. He wrote of suburban, gentile America with clueless banality.

In a lecture entitled Writing American Fiction, Roth set out the case for the emancipation of American literature from respectability and seriousness. He was ready to draw boldly upon everything around him and within him that was aggressive, crude and obscene. As Roth saw it, the age demanded nothing less.

The appearance of John Updike on the cover of Time magazine in 1968, and the runaway success of his novel Couples gave substance to the idea that America’s first post-puritan generation had arrived.

Whacking Off, a raucous and transgressive story from the manuscript of Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, appeared in the Summer 1967 issue of Partisan Review. It put masturbation front and centre in American life. (Jacqueline Susann remarked on the Johnny Carson Show on TV that she would love to meet Roth, but didn’t want to shake his hand.) There was a lot of sex around, and the hotshot young novelists were in the thick of it. Random House gave him an advance of $250,000 for Portnoy’s Complaint. It enjoyed an astonishing commercial success. Sex, in every permutation, gave Roth’s third novel a wild visibility. He often wrote of sex, but seldom with the sensuous delight of Updike. Roth’s most exuberant explorations of sexual freedom carried a deep knowledge of its costs: the burgeoning sense of guilt, and a dread of the emotional entanglements that relationships demanded. Sexual power could imprison and give immense pain.

During the 1970s Roth published his weakest books. Sales were “soft”, and he looked as though he was losing his place. The Breast (1972) was a short Kafkaesque tale of David Kepesh, a professor of comparative literature who found himself transformed one morning into a very large breast with five-inch nipples, who was visited for erotic purposes by “Claire”, a green-eyed blonde who taught in a Manhattan school, not to be confused with the actor Claire Bloom, with whom Roth was then living. It was followed by The Great American Novel. Asked by a Sports Illustrated journalist why he wrote about baseball, Roth remarked: “Because whaling’s been done.”

In My Life as a Man and The Professor of Desire (1977), Roth used surrogate narrators, and surrogates created by surrogates, which gave him an expansive field in which to play with fictional versions of his own life. But it was not clear that he had anything to say to his readers.

In the midst of his tumultuous relationship with Bloom in the 1970s, and the dislocation of annual moves between rural Connecticut (where Roth owned a farmhouse) and London, he produced a remarkable trilogy of novels later collected as Zuckerman Bound (1979-85), following the career of Nathan Zuckerman, a young Jewish writer struggling to reconcile art, family, literary fame and sex.

The first of the trilogy, The Ghost Writer, explores the wild idea that Anne Frank had not died in a Nazi death camp, but survived to escape to America, where she married (to his parents’ intense approval) Zuckerman.

An operation on a tear in Roth’s knee joint in 1987 was not a success, leaving him in great pain, suffering from insomnia and disorientation. He was prescribed the sedative Halcion (triazolam). The drug was banned in the UK in 1991, and subsequently in the US. It was later shown that patients taking Halcion had a high incidence of serious acute psychotic symptoms, including paranoia, memory loss, trembling, hallucinations and confusion. Roth was also prescribed Xanax, a high-potency benzodiazepine used in the treatment of panic disorder.

In his isolated Connecticut farmhouse, Roth went through a very contemporary kind of hell: drug-induced depression and personality disintegration. William Styron, his friend and neighbour in Connecticut, went through a similar experience with Halcion at virtually the same time. Roth’s friend Bernard Avishai helped him come through a cold-turkey withdrawal. In 1989, Roth had an emergency quintuple bypass operation.

Marking Roth’s survival from this ordeal, he and Bloom married in 1990. The story of his experience of Halcion was used in Operation Shylock (1993). A hostile review of that novel by Updike in the New Yorker (“The novel is an orgy of argumentation”) dumped Roth back into deep depression and wild mood swings, and he committed himself to a psychiatric hospital. The harrowing end of his marriage to Bloom and their bitter divorce in 1995, with Roth stone-like and hostile, is vividly described in Bloom’s memoir Leaving a Doll’s House (1996). Her bitter feelings about the failed marriage were reciprocated by Roth in I Married a Communist (1998).

Roth’s personal life afforded him little serenity, but his achievement in the 1980s and after represents one of the most remarkable creative moments in American literature. He staked a claim as a postmodernist in The Counterlife (1986) and Operation Shylock. But it was the exuberant, transgressive Mickey Sabbath, a maestro at loss, humiliation, and a sumo wrestler with death in Sabbath’s Theater (1995), who showed Roth to be a writer of a poignant humanity.

In American Pastoral, which won the Pulitzer prize in 1997, I Married a Communist and The Human Stain (2000), Roth engaged with American politics for the first time since his roasting of Nixon in Our Gang in 1971. In theory an upper West Side liberal, who had always voted for the Democrats, Roth declined to fit himself into predictable categories, liberal or otherwise.

One of his strongest motives for continuing to write fictions, he noted in Reading Myself and Others (1975), a collection of autobiographical essays, “is an increased distrust of ‘positions’, my own included”. He explored the unhealed scars of the Newark race riot of the 1960s in American Pastoral. In the character Swede Levov he created an American innocent, destroyed by the political wildness of that decade. But it was Levov’s daughter Merry, holed up in a Newark slum after committing a terrorist bombing, who gave American Pastoral its prophetic weight.

In I Married a Communist Roth explored themes of betrayal in the heyday of Popular Front leftism and McCarthyism. The Human Stain, awarded the Prix Médicis Étranger in 2002, was set in the year the House Republicans impeached Bill Clinton. In it, Roth explored transgression, and its endless consequences. An uttered impropriety (the word “spooks”) destroys Coleman Silk, a black classicist “passing” as a Jew, who is hounded out of his job, his reputation shredded, and then his life is destroyed.

It was a story based upon the experience of a friend, a professor of sociology at Princeton, who went through a similar moral and cultural lynching. An anonymous contributor to Wikipedia suggested that Coleman Silk was based upon the life of the writer Anatole Broyard. Roth wrote to Wikipedia to correct the misunderstanding, only to be told by the Wikipedia administrator that he, the author, was not a credible source. Citation of secondary sources was required. An open letter to the New Yorker soon followed in which Roth explained, patiently, the origins of The Human Stain. He was soon put in his place by American critics: what gave him the right to say what his stories were about, what they meant?

There are no happy endings in these books, which reflect perhaps the most remarkable act of literary understanding of the moment when the American people confronted (not for the first time, or the last) the death of innocence and hope.

Roth’s name was mentioned year after year when the Nobel prize in literature was pending. His many admirers regarded Roth as the most important novelist of his generation. In an exceptional homage to Roth’s standing, the Library of America began publication of a multi-volume edition of his complete works. In another act of tidying up, in 2001 Roth reorganised his books by protagonist: there were Zuckerman books, Roth books, Kepesh books. And in 2010 he added a category of short novels under the collective title Nemeses.

In The Plot Against America (2004) Roth returned to the Jewish world of his childhood in Newark. It was an exercise in counter-factual history, taking events belonging to “real” history, tweaking them with a plausible “what if”, and then following the logic of his speculations upon the life of a family.

“One of the reasons I could never write about what our family life was really like,” he remarked in an interview with Al Alvarez, “was because my parents were good, hard-working, responsible people and that’s boring for a novelist. What I discovered inadvertently was that if you put pressure on these decent people, then you’ve got a story.” The atmosphere of the novel, which began “Fear presides over these memories, a perpetual fear”, belongs as much to the post-9/11 world of all-invasive Homeland Security, as it does to the rise of a homegrown American Nazi president. The Plot Against America was awarded the James Fenimore Cooper prize for historical fiction in 2005.

Roth wrestled with the multiple woes of old age, illness and declining power in The Dying Animal (2001), Everyman (2006, awarded the Pen/William Faulkner award in 2007), Exit Ghost (2007) and The Humbling (2009). His protagonists struggle, scheme, yearn and resist, while clinging to their sexual fantasies and hope of regeneration. Roth found that growing old was unimaginable. “Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre,” reflects the unnamed protagonist of Everyman. As the narrator reaches the moment of death, Roth suggests the nature of our doomed, eager, hunger for life. The struggle against the remorselessness of age, decline, the loss of sexual potency, and the final insult of death itself, give Roth’s work an enduring power.

Following Everyman, Indignation (2008) and The Humbling, Roth published a fourth novella, Nemesis (2010), set in the Newark of 1944. His subject was the terrible polio outbreaks that came annually with summer, and how that inexplicable illness turned the community savagely upon itself. (Roth had recently been reading Camus’s The Plague.) The arbitrariness of the outbreak shakes the community and destroys Eugene “Bucky” Cantor, a dedicated, well-meaning PE teacher at Weequahic high school.

He was the kind of boring young man who was so unpromising a type for a writer like Roth. Putting Cantor under ferocious pressure by the communal fears which swept through the Jewish community, Roth portrayed a decent man destroyed by circumstances and by his own perhaps misplaced guilt at his responsibility for the disaster. Others survive the outbreak of polio, and most find ways to endure its consequences. Cantor was left a broken, maimed victim.

As his narratives grew more complex, his late style, memorably described by William Gass as something “rich, muscular, culturally complex [which] seems to come not from the end of a pen but through the flow of the voice,” became simpler and less raucous as it increasingly became the instrument of a mature artist at the very height of his creative powers.

In 2011 he won the Man Booker international award –“Hard to admire him,” wrote Carmen Callil on resigning from the award panel, “hard to see him on the long list, hard to award him this international prize” – and in 2012 the Asturias award. When, in 2013, New York magazine assembled a panel of 30 writers to select the greatest American writer, Roth won hands down. That year he was made a commander of the Légion d’honneur.

In 2012, Roth had mentioned, almost as an aside in a French interview, that Nemesis was going to be his last book. He had stopped writing in 2010, bought an iPhone, appointed a biographer (Blake Bailey), and was devoting himself to putting his archives in order. Bailey speculated that it would take a decade before he could finish the biography. In 2014, he conducted a filmed interview with Alan Yentob for the BBC that he said would be his last public appearance.

“I’m 78 now,” Roth had told the French interviewer. “I know nothing about America today. I see it on the television, but I don’t live there any longer.”

• Philip Milton Roth, novelist, born 19 March 1933; died 22 May 2018.