Coronavirus vaccine 'stimulates antibody and T-cell response' – what does this mean?

Hopes of a coronavirus vaccine have been raised after a promising candidate stimulated an immune response in an early-stage clinical trial.

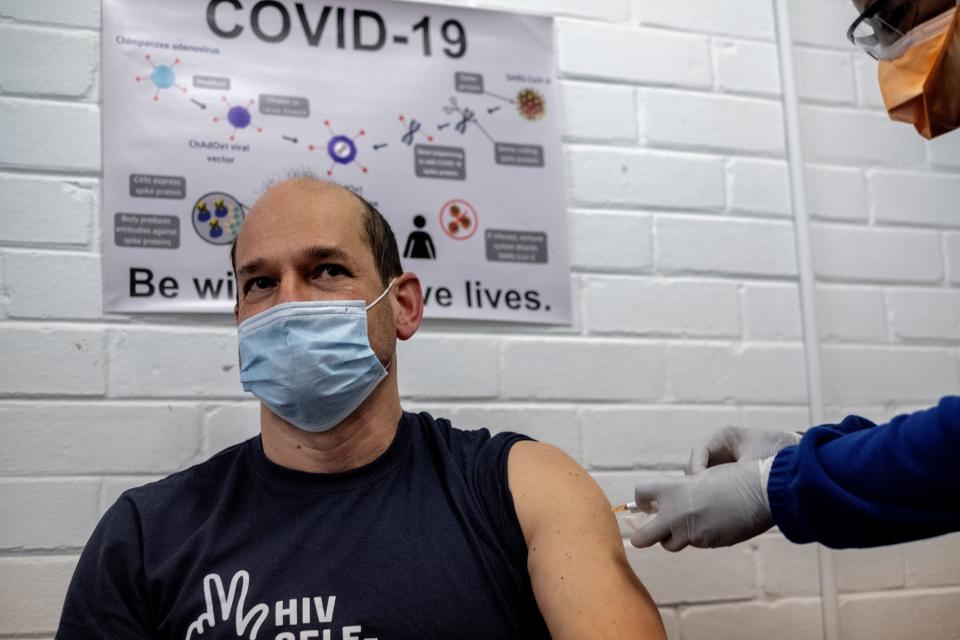

Scientists from the University of Oxford created a jab that was given to hundreds of healthy volunteers.

Read more: What is the coronavirus treatment being hailed a 'breakthrough'?

They found the vaccine induced “strong antibody and T-cell immune responses up to day 56 of the ongoing trial”.

A T-cell response was triggered within 14 days, while antibodies were detected 28 days after vaccination, “inducing strong immune responses in both parts of the immune system”.

Experts have hailed the results “promising”, “encouraging” and “extremely positive” – but what do they mean?

What are antibodies and T-cells?

When the immune system encounters a pathogen, like a virus, cells work to create proteins called antibodies.

These are specific to each pathogen and lock onto their surface, neutralising or “marking” it for destruction by other immune cells.

When it comes to T-cells, there are two types: helper and killer.

Helper T-cells stimulate antibody production and assist in the development of killer cells.

Killer T-cells directly destroy body cells that have already been infected by a pathogen.

Read more: 'Broken heart syndrome' on the rise during coronavirus pandemic

T-cells also send out messages that instruct the rest of the immune system to ramp up its response.

Antibodies and T-cells take time to develop, but tend to stick around at low levels in the bloodstream for a relatively long time.

When a pathogen is encountered again, the immune system ramps up production of these “weapons”, preventing a virus or bacterium from taking hold for a second time.

This is the principle behind vaccines; exposing an individual to a harmless amount of an infection that allows the immune system to recognise it if it were to invade the body.

Why is both an antibody and T-cell response important?

Officials often talk about antibody tests being the way to determine a past coronavirus infection, however, the immune system is rather more complex than that.

“Antibodies are in fluids and can encounter viruses when they come into the body,” Professor Sarah Gilbert, lead researcher of Oxford’s vaccine development programme, said at a Science Media Centre briefing.

“Antibodies bind onto the outside of the virus to stop them infecting cells. It blocks it from causing infection.

“T-cells don’t recognise free viruses but [instead the] cells infected with viruses that can take over and create virus factories that can create much more [viruses].

“The two work together and are completely complementary.”

Read more: ‘Remains to be seen’ if coronavirus causes brain damage

With a vaccine being hailed as the way back to normality, the scientists hope stimulating both aspects of immunity will lead to lasting protection.

“The immune system has two ways of finding and attacking pathogens – antibody and T-cell responses,” said Professor Andrew Pollard, chief investigator of the Oxford study.

“This vaccine is intended to induce both, so it can attack the virus when it’s circulating in the body, as well as attacking infected cells.

“We hope this means the immune system will remember the virus, so our vaccine will protect people for an extended period.

“However, we need more research before we can confirm the vaccine effectively protects against [the coronavirus] infection and for how long any protection lasts.”

How optimistic should we be about the results?

Evidence of a vaccine triggering an antibody and T-cell response is a promising step, however, experts have warned much more research is required to be sure a jab is both safe and effective.

“The initial results of the Oxford vaccine trial are promising,” said Dr Doug Brown from the British Society for Immunology.

“This paper shows the vaccine elicited both antibodies and T-cell immune response against [the coronavirus] in the majority of patients after a single dose.

“This is a good first sign but we still have yet to understand whether these immune responses will have an effect if those individuals encounter the virus in the future.

“Developing new vaccines is a highly complicated process and success is by no means assured.

“Although the results of this trial are an important step forward, they are not the end of the story.”

Professor Stephen Evans from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine called the results “exciting”, but added “it is not the end of the road, far from it”.

“For the vaccine to be really useful, we not only need the larger studies conducted where COVID-19 [the disease caused by the coronavirus] is still occurring at a high rate, but we need to be reasonably sure that the protection lasts for a considerable time,” he said.