Coronavirus: what impact could it have on the heart?

The coronavirus may be more dangerous in patients with underlying heart disease, research suggests.

Scientists from Zhongnan Hospital in Wuhan, where the strain emerged, have warned damage to the heart is “significantly associated with fatal outcomes” among those with the previously-unknown infection.

Limited evidence suggests catching the virus could even trigger cardiovascular disease, with one previously healthy woman requiring treatment for heart failure a week after she developed the tell-tale fever and cough.

Why this occurs is unclear, however, scientists from the University of Texas in Houston worry “the high inflammatory burden” of the virus may lead to “significant cardiovascular complications”.

Other experts have called for additional research, stressing the studies so far do not prove a “‘virus-to-heart’ toxicity link”.

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, at the end of last year.

Since the outbreak was identified, over 553,200 cases have been confirmed across more than 170 countries on every inhabited continent, according to John Hopkins University.

More than 127,500 patients are reported to have “recovered”.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

Cases have been plateauing in China since the end of February, with the US and Europe now considered the worst-hit areas.

The UK has had more than 11,800 confirmed cases and 759 deaths.

Globally, the death toll has exceeded 25,000.

The coronavirus aside, heart disease is responsible for one in four deaths in the UK.

Across Europe, it is behind nearly half (45%) of all fatalities.

Coronavirus: evidence that suggests it affects the heart

Three research papers, all published in the journal JAMA Cardiology, investigated a potential link between the coronavirus and heart health.

Scientists from Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan, looked at 187 coronavirus patients who were admitted between 23 January and 23 February.

Of these patients, 144 (77%) were discharged and the remaining 43 patients (23%) died.

Overall, 66 (35%) had underlying heart disease including high blood pressure, coronary heart disease – when the coronary arteries become too narrow, and cardiomyopathy – when the heart muscle becomes enlarged or thickened.

Of those without pre-existing heart disease and normal troponin levels, 7% died in hospital.

Troponins are groups of proteins in heart muscle that help regulate contraction. When the heart is damaged, they are released into the bloodstream, which doctors use to aid diagnosis.

Of the patients with underlying heart issues but normal troponin levels, 13% died in hospital.

This rose to 37% for the patients without heart problems but elevated troponins, and 69% for those with underlying cardiovascular disease and excessive levels of the proteins.

The scientists concluded damage to the heart is “significantly associated with fatal outcomes” with the coronavirus, while patients with cardiovascular disease but no injury to the heart have a “relatively favourable” prognosis.

Calling for more research, Professor Kevin McConway from The Open University said: “[The study] only [looked at] patients who were hospitalised and most people with [the coronavirus] are not hospitalised.

“So it can’t tell us about the general chance of heart damage to people with [the coronavirus], including the majority who do not go to hospital, as well as the minority who do.

“And the number of patients in that study was not large and most of them had existing diseases that are already understood to increase their risks, so the study can’t really tie down the risks to people without underlying disease very precisely, even for those who are hospitalised”.

The circulating coronavirus is one of seven strains of a class of viruses that are known to infect humans.

Four of these strains trigger the common cold. Although usually mild, elderly people with underlying health problems have required hospital care if they catch the sniffles.

Of all the coronaviruses, the circulating strain is said to be most genetically similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

Heart attacks were reported after patients overcame Sars, however, “most of the data” was “anecdotal”.

A study of 75 Sars patients found two in five died as a result of a heart attack, however, these findings were not repeated elsewhere.

One case report even suggests the coronavirus could trigger heart problems.

Scientists from the University of Brescia, Italy, looked at a woman who developed the signs of heart failure a week after the onset of the coronavirus’ symptoms.

The otherwise healthy 53-year-old woman arrived at an A&E unit after battling severe fatigue for two days.

The unnamed woman, who had endured a cough and fever for a week, tested positive for the coronavirus.

Tests revealed parts of the walls of her heart were abnormally thick, resulting in contractility being reduced by up to 35%.

The woman stabilised after treatment, which included anti-viral drugs and heart-failure therapy.

Coronavirus: how could it affect the heart?

Viral infections are recognised as one of the most common causes of inflammation of the heart muscle, which reduces its ability to pump blood efficiently around the body.

Although an infection of the airways, the coronavirus may replicate and spread through the blood and lymphatic system, entering the heart.

There are, however, “no reports of coronavirus RNA in the heart, to date”.

The coronavirus is an RNA virus. In simple terms, RNA is a precursor to DNA.

It may also trigger inflammation that damages the cardiovascular system.

Biomarkers have suggested a “high prevalence of cardiac injury” in patients hospitalised with the coronavirus.

“Given the high inflammatory burden of [the coronavirus] and based on early clinical reports, significant cardiovascular complications with infection are expected”, wrote the scientists from the University of Texas, Houston.

“The prevalence of cardiovascular disease in non-hospitalised and milder cases is likely lower”.

Early research suggests four out of five cases of the coronavirus are mild.

“Many viruses can affect the heart muscle as well as the lining around the outside of the heart that lubricates the heart's movement,” said Professor Robert Storey from the University of Sheffield.

“However, there is accumulating evidence that [the coronavirus] is associated with a higher risk of heart muscle damage than most common viruses.

“This may partly relate to entry of the virus into the heart muscle cells and partly to the overwhelming inflammation that some patients experience, which can injure the heart muscle.

“Inevitably patients with heart muscle damage are likely to have worse infection and inflammation so it is not surprising those with such damage are more likely to die.

“Similarly, patients with pre-existing heart or lung disease may have less reserve to deal with the consequences of the infection and are at higher risk”.

Professor Storey worries heart-attack patients may be less likely to seek help amid the coronavirus pandemic.

“This is a worrying trend because it is placing patients at higher risk from the heart attack due to delays in diagnosis and treatment,” he said.

“Lung infections are known to increase the risk of heart attack in the weeks after and so it is important people do not stay at home without seeking advice or, if appropriate, calling for an ambulance to ensure they receive the most effective treatment."

While the coronavirus strain may be new, one cardiologist reassured doctors are well versed at caring for heart patients.

“Physicians, intensive care doctors and cardiologists are already very familiar with dealing with the heart problems that can be seen with [the coronavirus], such as abnormal heart rhythms, impaired pumping function and inflammation,” said Professor Tim Chico also from the University of Sheffield.

“Although we do not have a specific [coronavirus] treatment yet, it is possible to manage these complications until the patient recovers.”

With the circulating strain virtually unheard of at the start of the year, one expert stressed the importance of additional research.

“More robust studies to examine a potential ‘virus-to-heart’ toxicity link are now needed”, said Professor Naveed Sattar from the University of Glasgow.

“I say this, since current studies have deficiencies and are as yet not considered definitive in the proof of this link.

“I am sure more robust studies will be urgently started in differing parts of the world.”

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets coughed or sneezed out by a patient.

There is also evidence it can be transmitted in faeces and urine and survive on surfaces.

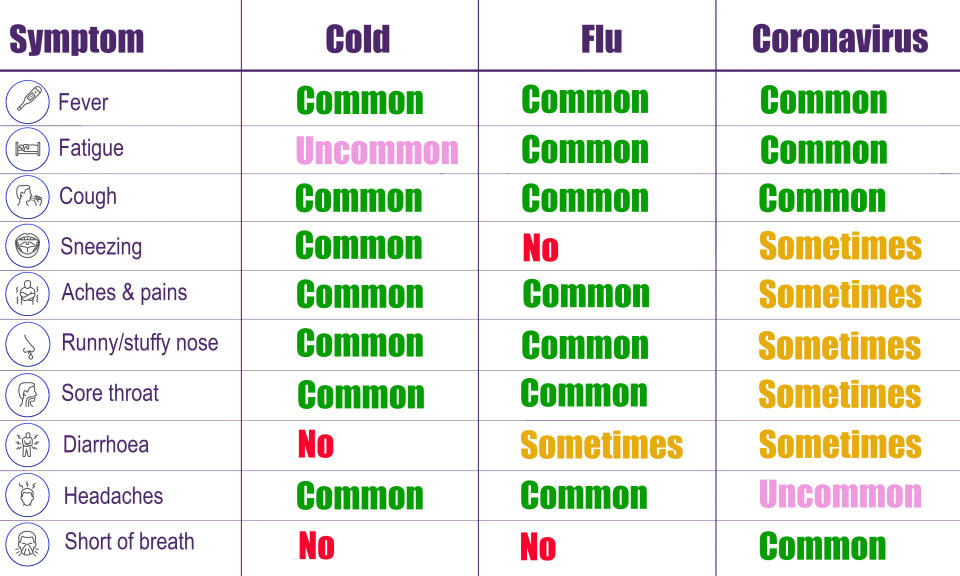

Symptoms tend to be flu-like, including fever, cough and slight breathlessness.

Pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the infection by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.