Coronavirus' death rate found to be lower than World Health Organization estimates

The coronavirus’ death rate may be lower than the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated, research suggests.

With the virus virtually unheard of at the start of the year, experts have been racing to uncover how dangerous it really is and the patients most likely to succumb to complications.

At the beginning of March, the WHO announced the virus had killed 3.4% of patients worldwide, which other experts called a likely “overestimate”.

To learn more, scientists from The University of Hong Kong looked at the 48,557 confirmed cases that had arisen as of 29 February in the Chinese city Wuhan, where the outbreak emerged.

They found the average death rate among patients under 30 was 0.3%, rising to 0.5% for those between 30 and 59, and 2.6% for people aged 60 or above.

Overall, they calculated the fatality rate to be 1.4%.

Although “promising”, experts have stressed estimating death rates in the midst of an outbreak is “fraught with difficulties”.

Latest coronavirus news, updates and advice

Live: Follow all the latest updates from the UK and around the world

Fact-checker: The number of COVID-19 cases in your local area

Explained: Symptoms, latest advice and how it compares to the flu

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in Wuhan at the end of last year.

It has since spread to more than 160 countries, across every inhabited continent.

Since the outbreak began, more than 246,000 cases have been confirmed, of whom over 86,000 have “recovered”, according to John Hopkins University data.

Cases have been plateauing in China since the end of February, with Europe now the epicentre of the pandemic.

Italy alone has had more than 41,000 confirmed cases and over 3,000 deaths.

In the UK, 3,269 people have tested positive for the virus, of whom 145 have died.

Globally, the death toll has exceeded 10,000.

‘This is a very important new piece of data’

The new coronavirus was officially identified as the cause of an outbreak of illness in Wuhan on 9 January.

In an attempt to combat the infection, scientists quickly got to work uncovering how severe the infection could be.

Using “public and published information”, the Hong Kong scientists looked at the 48,557 cases in Wuhan, of whom 2,169 died.

Based on this, the scientists calculated the overall “symptomatic” death rate in Wuhan at the start of the outbreak to range from 0.9%–to-2.1%, averaging at 1.4%.

Compared to those aged between 30 and 59 , the patients aged 60 or over were on average 5.1 times more likely to die “after developing symptoms”, according to results published in the journal Nature Medicine.

Patients without symptoms would likely have gone unreported and not been included in the analysis.

“This is a detailed epidemiological analysis and the results are cautiously encouraging, in that they indicate a lower fatality rate from [the coronavirus] than has thus far been estimated,” said Professor Robin May from the University of Birmingham.

“Using patient data from the original epicentre of the outbreak, Wuhan, they show an overall death rate of around 1.4% of symptomatic cases, which is lower than previous estimates.

“They also show that mortality rates appear to be very low for people under 50 (around 0.3-0.5%) which is, again, promising.”

He stressed, however, the same results may not apply to other areas of the pandemic.

Death rates can vary according to the strength of the country’s health service.

“One important caveat, is this study is based primarily on data from Wuhan and therefore does not necessarily reflect mortality rates that may be seen in other areas of the world,” said Professor May.

“As with all epidemiological models, it also relies on various assumptions which, since we still know relatively little about the course of this infection in human populations, may not be entirely accurate.

“That said, however, this is a very important new piece of data that will help guide the public health response to this pandemic.”

Why is the coronavirus’ death rate so difficult to calculate?

The Hong Kong research comes after WHO’s director-general Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said on 3 March: “Globally, about 3.4% of reported [coronavirus] cases have died.”

Death rates are defined as the percentage of cases that die.

This is different from the death toll, which is the total number of deaths.

On 29 January, the WHO cited a likely death rate of 2%.

Just a few days later, the Chinese National Health Commission reported it appeared to be 2.1%, based on 425 deaths among 20,438 confirmed cases.

On 20 February, a WHO-China joint statement put the death rate at 3.8% based on 2,114 deaths among 55,924 cases.

The UK is only routinely testing hospital patients for the coronavirus, who are severe by definition.

With early research suggesting the infection is mild in four out of five cases, many non-serious incidences in the community will likely go unreported, skewing the death rate.

“We do not report all the cases,” Professor John Edmunds from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine previously said.

“In fact, we only usually report a small proportion of them.

“If there are many more cases in reality, then the case-fatality ratio will be lower”.

Asymptomatic infections similarly confuse how the death rate is calculated.

“Since subclinical [an infection not severe enough to cause “observable” symptoms] and asymptomatic infections have been reported, [the] true case-fatality ratio cannot be estimated until population surveys can be undertaken to estimate the proportion of individuals that were infected but did not manifest symptoms,” Dr Toni Ho from the University of Glasgow previously said.

Taking into account those with mild or no symptoms, Dr Christl Donnelly – from Imperial College London – estimated a 1% fatality rate appears more likely.

“In an unfolding epidemic it can be misleading to look at the naïve estimate of deaths so far divided by cases so far,” she previously said.

“The infection-fatality ratio is the proportion of infections (including those with no symptoms or mild symptoms) that die of the disease.

“Our estimate for this is 1%.”

Death rates can also change if countries alter how they define a case.

Cases “spiked” in China when it started defining a patient as “definitely infected” if they presented with symptoms, alongside a CT scan showing a chest infection.

Beforehand, patients were confirmed via a nucleic acid test. Nucleic acids are substances in living cells, making up the “NA” of DNA.

As a result, cases appeared to spike overnight in mid-February, despite one expert stressing it was “solely an administrative issue”.

Quarantines and other interventions can also make the population less exposed to the infection, driving death rates down.

A lack of awareness at the start of the outbreak may have meant patients only sought treatment when their symptoms became severe.

Death rates could also reduce as patients start “self-identifying” their symptoms earlier on.

“The best estimates of case-fatality rates would have to occur once an epidemic was over,” Dr Tom Wingfield from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine previously said.

“Estimating in real time during the epidemic is fraught with difficulties”.

What is the coronavirus?

The coronavirus is a strain of a class of viruses, with seven known to infect humans.

Others include the common cold and severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

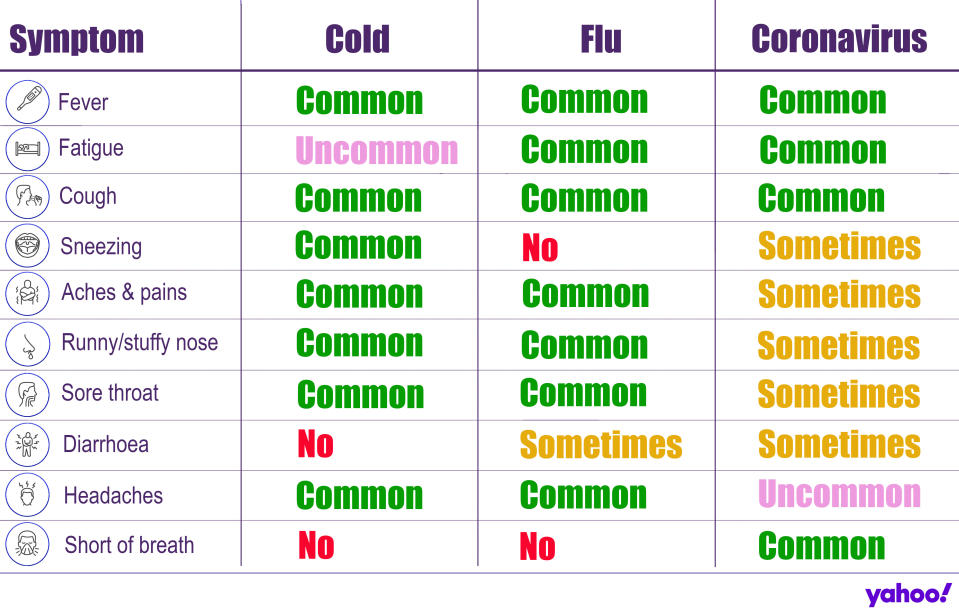

The coronavirus tends to cause flu-like symptoms initially, such as a fever, cough or slight breathlessness.

It mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets coughed or sneezed out by a patient.

There is also evidence it can be transmitted in faeces and urine.

While most cases are mild, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs, causing them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the infection by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.