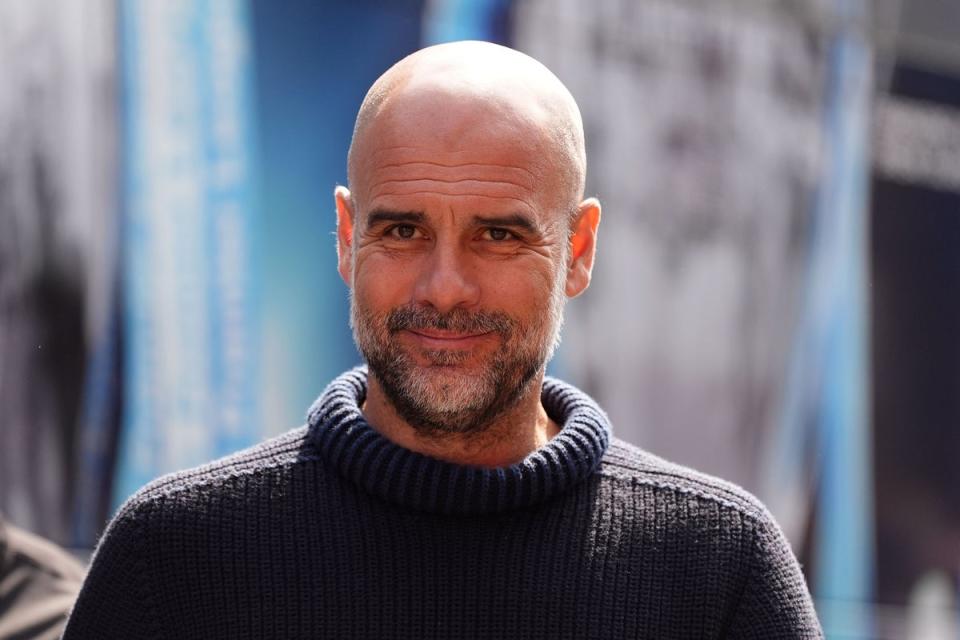

The legacy of Pep Guardiola’s Man City – and why they may never be truly loved

Pep Guardiola is on the brink of history. “One game, destiny in our hands,” he said, relishing the scenario rather than deflecting attention from it. A fourth consecutive English title would be an unparalleled achievement. It would also be a very popular one; within the Manchester City fanbase, anyway.

And in the wider world? “F***, I don’t know,” replied a dismissive Guardiola. “I don’t go knocking on doors asking people what they think. I don’t know, honestly.”

And if he is sufficiently busy that he scarcely had time to double up as a pollster, canvassing opinions, if many people in football are insulated from the outside world, there is a broader question of how City are viewed. As a great team? Definitely, and they will be even if they lose to West Ham on Sunday and Arsenal supplant them at the top of the table. As the best side in Europe? They were last season but, however often they are described as such, that status surely belongs with either the relentless Real Madrid or even Xabi Alonso’s unbeaten Bayer Leverkusen, based on the evidence of the current campaign. As a side whose achievements often come with a caveat? For now, certainly, given that 115 Premier League charges still hang over City. That said, if the eventual verdict is that City breached regulations for years to create the conditions for their current era of dominance, the fundamental fault for that was not committed by Guardiola or his players.

Step away from the toxic tribalism and the whataboutery, however, and there is a broader question. Sometimes there is no critical mass, simply because of the clubs involved. Great teams have often been both loved and hated, in part because they tended to represent Manchester United or Liverpool. Historically, City provoked strong views from the supporters of fewer other clubs.

Now there is little doubt that Guardiola’s peers admire him. He feels his side will get the credit from their achievements; “in world football, for sure”. There is respect, but perhaps not love. There may have been more romance to United’s 1999 treble than City’s 2023 version. One accusation is that there is too little jeopardy when City play; that perpetual possession takes their opponents out of a game, that too many matches are a formality.

Yet not all. Stefan Ortega’s late save from Tottenham’s Son Heung-min on Tuesday illustrates their eighth straight win was no inevitability. Titles can be won or lost in such moments. Guardiola remembers many of them. He cites Romelu Lukaku’s late miss in last year’s Champions League final with great frequency. He knows it is very possible that, after eight years in Manchester, he would have no European silverware.

He may be seeing jeopardy where few others spot it in Sunday’s clash with West Ham. “We would like to be 3-0 up in 10 minutes but it is not going to happen,” he said. Yet part of the paradox of this City team is that a side defined by a quest for control have some of their defining games in matches when they lose it: think of most of their Champions League exits, high on drama, low on predictability. City have won five of the last six league titles, but not without obstacles. “I have the feeling it will be an Aston Villa game,” said Guardiola of West Ham: two years ago, on the final day, City went 2-0 down to Villa, before scoring three times in five late minutes. Ilkay Gundogan scored the title-winning goal then; four years before Guardiola’s arrival, Sergio Aguero got an even later one in 2012.

“The Aguero moment,” Guardiola said. It is the most famous goal in City’s history. The Gundogan moment is proof the class of 2024 could cement themselves in City folklore in a similar manner this weekend. “The fact that they lived it not a long time ago, a lot of the players are still here,” Guardiola said.

Maybe the second contradiction in this City side is that, while Guardiola is indelibly associated with short passing, with clinical attempts to dissect defences, two of his defining players have a fondness for the spectacular. Phil Foden’s long-range goals have helped him be named Footballer of the Year; Kevin de Bruyne will often attempt the most audacious pass possible and sometimes execute it. When Erling Haaland is at his best, however, there can be something robotic about the man-mountain in attack while, when City pass opponents to death, their football can feel more bloodless than Jurgen Klopp’s thunderous assault on the senses.

Guardiola has had to rebut suggestions City are boring; if that stems from their habit of winning everything, of sweeping up domestic cups while on the brink of a sixth league title in seven seasons, his answer this week was to argue it did not stem from a financial advantage. United and Chelsea spent more, he said. City’s wage bill was nevertheless the highest last season; it may be again. If money explains part of the antipathy, the feeling their superiority begins with the budget, which has largely been well spent on a man often described as the world’s best manager and a group of outstanding footballers, they have now ascended to a level where success seems routine, almost unremarkable. And so, unloved but exceptional, Guardiola’s City stand on the brink of something no one else has done before.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport