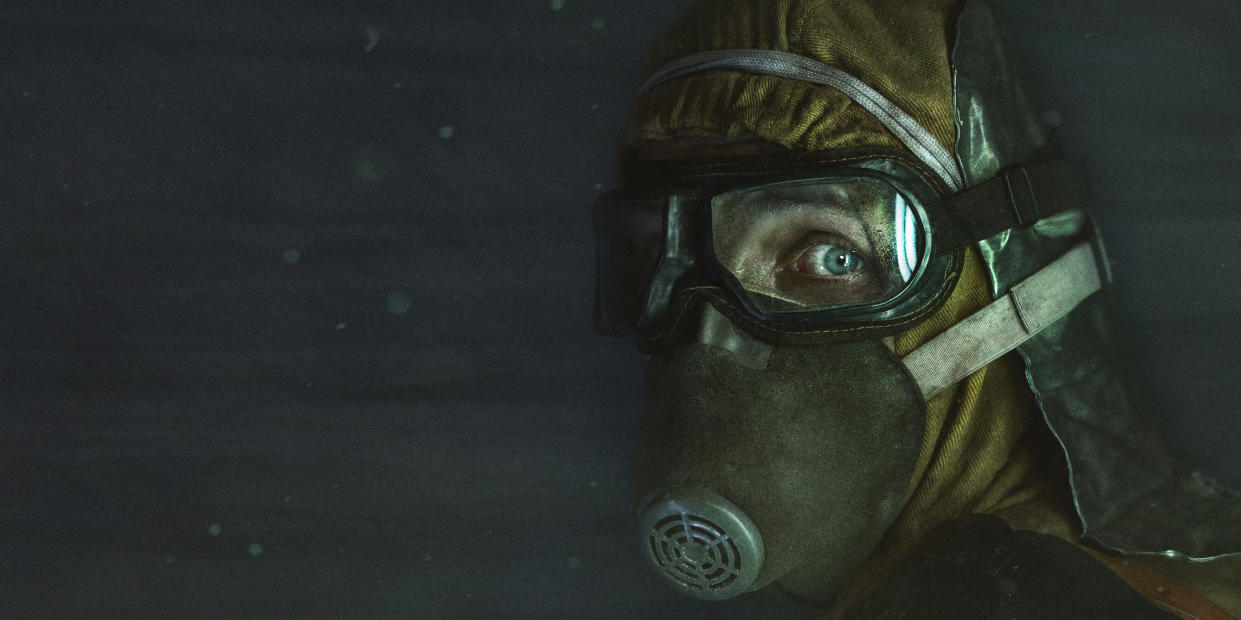

'Chernobyl': How historically accurate is the hit HBO miniseries?

The final episode of the miniseries Chernobyl aired on Tuesday, bringing the harrowing true story to a dramatic close.

In contrast with HBO’s other flagship TV show Game of Thrones, Chernobyl was announced with very little fanfare. However, it has quickly become the highest ranked show ever on IMDb with a rating of 9.7 from nearly 140,000 reviews.

The tragedy of 26 April 1986 caused shockwaves around the world, and ultimately forced the Soviet Union to admit that there were problems with their nuclear reactors.

The five-part instalment attempted to untangle the mysteries surrounding Chernobyl and offer an insight as to how the accident happened and the resulting efforts to cover-up the enormity of the disaster.

But just how accurate was it?

Dr Claire Corkhill, a researcher of nuclear waste disposal management at the University of Sheffield, has joint projects with people in Ukraine and Japan to help with cleanup at Chernobyl and Fukushima. She’s been a vocal supporter of the show on Twitter.

She told Yahoo Movies UK: “HBO did fantastically in their portrayal of nuclear reactors, it’s not very easy to explain nuclear engineering in a drama series.

“I wanted to do the live tweets because they didn’t clarify everything instantly all of the time and I wanted to give a bit of background information so people know what’s going on.

“But they did a really good job of explaining the science and keeping true to the story.”

The first episode of the series opens with a bang - literally - with the show putting the explosion that happened on that fateful night front and centre. Local firefighters are promptly scrambled to the scene, but it’s clear they were not prepared for what they faced. Many of the first responders died from radiation poising in the immediate aftermath.

“Some of the things that I’m not 100% sure were entirely accurate were in the first episode, when the firefighter picked up a block of graphite and it instantly burnt his hand, I don’t think radiation burns come that quickly, they’ll appear more in a matter of hours or days,” she added.

“The make up and prosthetics of the radiation burns were horrific and actually, from what I’ve read, it probably was a lot worse than that. In the HBO series they didn’t show the full extent of it.”

In order to contain the spread of radiation as quickly as possible, more than 600,000 people were conscripted in the clean up effort, from stripping the top five centimetres of soil to creating a concrete shelter structure around the reactor building 4, often known as the ‘Sarcophagus’. These people were given the blanket term ‘liquidators’. A number are thought to have contracted cancer and died as a result of the proximity to the power plant.

“I knew quite a lot about Chernobyl because I have been there before as part of my research and I work with the Ukrainian Institute of Science on trying to understand how to remove the fuel, but I didn’t know so much about the human side of the story, that was something I’ve learnt from the programme.”

Slava Malamud, 44, is a freelance journalist and maths teacher living in Baltimore, Maryland, but grew up in a part of Moldova called Transnistria, about 600km to the south of Chernobyl, and was just 11 years old when the explosion happened.

He said: “I first started watching the series because there was word from Russia that America was going to do a show about Chernobyl and that it would not be a caricature. I was curious about it.

“It struck me from the very first scene that they paid such extraordinary attention to detail, the reality of not only how it looked but how it felt.

“There were little things I remember from my childhood, like the school uniforms, the shoes, the interior design of the apartments we used to live in.

“One of the boys was holding a brown bag with a cartoon character on it, identical to the one I used to have.”

Valery Legasov (Jared Harris) was a scientist brought in front of the government committee by Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skarsgård) to lead the clean up effort. Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson), a nuclear physicist - and a fictional character who represents the efforts of hundreds of real-life scientists - from Minsk, joins them when she discovers a spike in radiation levels.

The fire at the plant is extinguished by episode three after the military dumps boron and sand. But it quickly becomes apparent that the nuclear meltdown has begun and is in danger of contaminating the groundwater, potentially affecting millions of civilians. To prevent it from melting through the concrete foundations, around 400 miners are transferred to the plant to dig a tunnel underneath so that cooling agents can be installed.

Slava said: “The characters behaved exactly as the people used to, Dyatlov (the supervisor at the plant that night) as the misanthropic chain-smoker who is never satisfied, the chief miner is every single grizzled drunk Russian professional I’ve ever worked with, the type of guys who will never ever open up to you, but if you earn their trust they will be extremely kind, caring and selfless.

“Legasov is like the typical ‘intelligentsia’, very smart and brilliant, always caring about saving the world, the greater things in life.

“Forget the small things such as licence plates, this looks like the Soviet Union.

“To me, the fact that the actors were speaking with British and Irish accents was not strange. In Soviet war films, German soldiers spoke Russian and the viewers were supposed to use their imagination, so it just added another aura to the show.

“Of course there was a lot of artistic license, the courtroom scene was all for dramatic effect, mainly to explain to the viewer what happened, and the character of Ulana Khomyuk was created just for the show.

“The changes did not happen in one fell swoop, but over a couple of years.

Read more: See Mackenzie Crook as Worzel Gummidge

“Also there was some dialogue I felt could not have happened in real life, for example between Legasov and Shcherbina where they basically bash the Soviet Union and officials, that sounded a little forced and like they were trying to make a point.

“They were both true believers of the system, neither were angels, but they were in the circumstance where they had to do the right thing and they did it.

“Most of the inaccuracies came from a storytelling perspective, the fact that they had to condense so many months and years into five episodes.”

By recommending the drama to his stepfather, the retired Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Veytsmanan, an unknown truth came to light - he had been a liquidator and ordered to go help with the evacuation at the villages surrounding Chernobyl for three weeks.

“It was the craziest thing, he said ‘I don’t want to watch it because I’ve been there’.

“When I asked him how this had never come up in conversation, he told me ‘well, you never asked me’, and when I asked him to talk more about it he said ‘I can’t say because I signed a paper and I can’t violate that’, which is such a Soviet thing to say.”

Chernobyl is available to watch in full on NOW TV.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies