How Britain became hooked on sickness benefits

Britain is in the grip of its worst sickness crisis in decades, and the Treasury is growing increasingly concerned.

According to the latest predictions, one in 12 working-age Britons are expected to claim sickness benefits by the end of the decade, fuelled by a surge in mental health conditions.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the Government’s tax-and-spending watchdog, pulled no punches in its latest analysis of the problem as it highlighted the “rapid increase” in sickness benefit claims post-Covid.

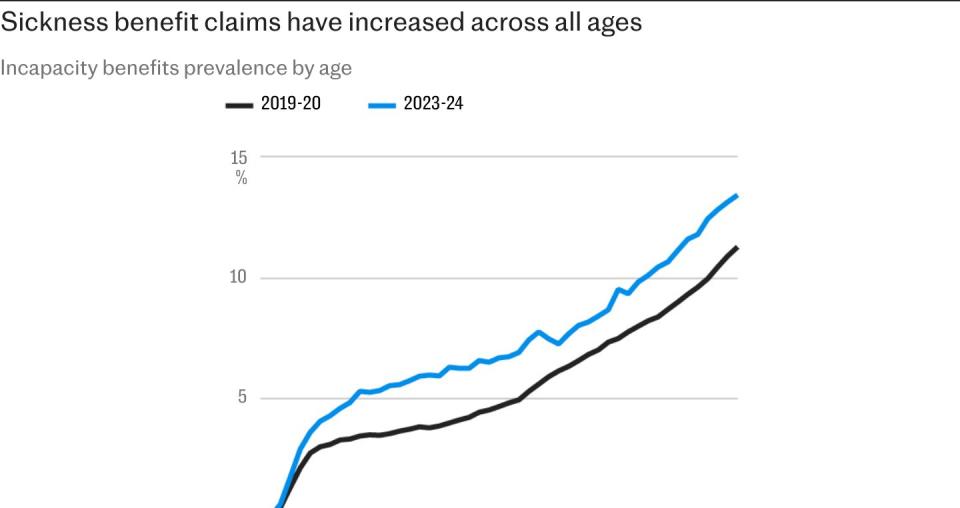

It said the share of the working-age population currently receiving incapacity benefits reached a post-financial crisis high of 7pc in 2023-24.

Worse still, it warned this was expected to hit an all-time high of 7.9pc in 2028-29, surpassing rates last seen in the 1990s during a period of major industrial decline.

“This reverses the steady decline in caseload prevalence from the early 2000s to mid-2010s,” the OBR said in its latest welfare trends report.

There are now just under 2.8m people who are neither in work nor looking for a job owing to ill health.

The OBR said deteriorating health, as well as changes in the way people claim, had all contributed to an increase in welfare payments.

It comes just a day after the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) warned of an “extraordinary” rise in benefit spending to support people with disabilities and long-term health conditions, which it said was on course to climb above £100bn by the end of the decade.

The think tank said spending on welfare for people with disabilities had continually overshot the official watchdog’s forecasts.

Spending this financial year alone on incapacity and disability benefits is expected to be £87.2bn. This is £20.8bn higher than was forecast in 2021, equivalent to roughly a third.

“This extraordinary rise will put substantial pressure on the public finances,” the IFS said.

Carl Emmerson, the deputy director of the IFS, said there has been an increase in claims across the board.

“We’re seeing a lot more children, a lot more working-age people, and a lot more pensioners receiving those benefits,” he said.

“And of course, it’s incredibly worrying for people to the extent to which their health is deteriorating and it’s affecting their well-being. So there’s a big societal challenge.”

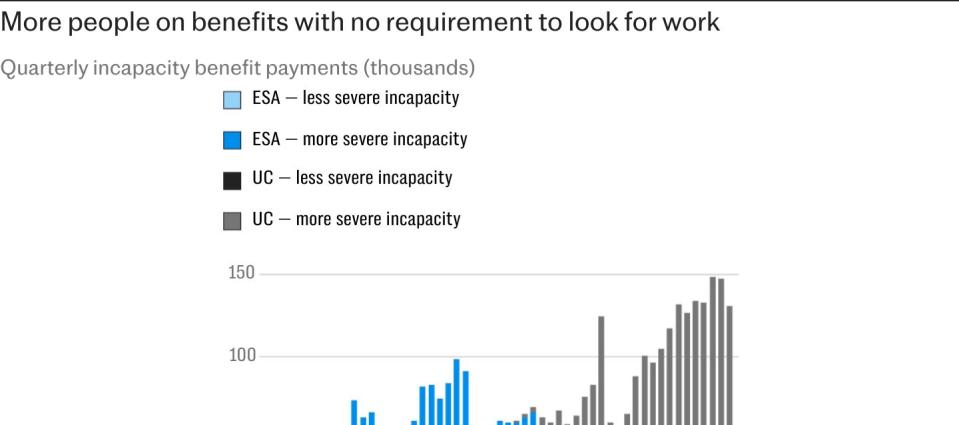

Official data show the post-pandemic rise in claims has been stark. Recent analysis published by the Department for Work and Pensions signalled that of the 2.7m universal credit decisions linked to deteriorating health, two thirds of claimants were deemed to be too sick to even look for work.

These people receive a higher level of benefits and have very little engagement with the jobcentre, if at all.

Additional DWP data shows that 69pc of people claiming health-related universal credit between January 2022 and May 2024 were recorded as having mental health disorders.

This includes half of those claimants considered capable of having a job following a work capability assessment (WCA) and 90pc of those who are not required to look for a job.

There is also evidence that people are increasingly living with multiple health conditions.

Almost half of health claims were also linked to people with musculoskeletal conditions, such as back and neck pain.

However, the OBR also noted that “only a minority of the recent rise in incapacity benefits” reflected a higher number of people initiating claims.

Growth was driven primarily by fewer people dropping their claims, it said, as well as fewer people having their claims denied.

They may also reflect changes in the characteristics of claimants such as the type and severity of their health conditions

Part of the process for verifying claimants used to include people having to show up to the jobcentre with a fit note obtained from a GP signing them off work.

However, the pandemic prompted the DWP to amend this process by adopting a trust system, which has been retained ever since.

The OBR also noted that changes introduced in 2017 by former chancellor George Osborne that reduced benefit payments to people with mild health conditions to save money may have backfired.

Rather than reducing claims, the OBR said this policy decision may have had the opposite effect by encouraging many to apply for the more generous level of benefits, which had no strings attached.

From a broader perspective, the watchdog also judged that “part of the recent strong growth in incapacity benefits caseloads has been driven by cost-of-living pressures driving up applications and take-up, meaning growth rates will slow as real household disposable incomes recover”.

The previous Tory government announced a massive overhaul in the way sickness benefits are administered in a move designed to save £3bn, yet it is unclear whether the Labour administration will continue with these reforms.

Mr Emmerson said that solving Britain’s worklessness crisis is the “big challenge” for the economy, albeit one that cannot be easily solved.

He said: “If these individuals can be helped to get healthier and remain in the labour market, that would be good for them, and it’ll be much better for the public finances.

“But it’s certainly easier said than done to carry out reforms that get that bill down.”