Why Bo Boroski quit reffing after 3 straight Final Fours: 'Most wouldn't have walked away'

INDIANAPOLIS – Bo Boroski was a stone faced, take no heat, dramatic-foul-calling official, who sometimes diffused coaches' tirades with humor and who always, he says, used empathy to figure out why a player was throwing his hands up at him or why a coach was so outraged he was spitting in his face.

Boroski was accurate. The NCAA keeps detailed stats on its officials' whistle blowing accuracy and Boroski almost always landed at the top for correct calls and appropriate no calls, which put him in elite league and tournament positions.

For more than 20 years, Boroski took the court for Division I men's basketball matchups. For the last 15 years, he refereed 90 games a season. And he officiated the past three Final Fours, an A-list gig, a dream for anyone who has ever donned the stripes – a dream most officials wouldn't walk away from.

But Boroski had a secret as he called the 2022 Final Four game between Duke and North Carolina inside the Superdome in New Orleans. Few knew, except his wife and a close circle of confidantes. That game would be his last.

Boroski, 47, was ready to part ways with a life that no one can understand unless they have been on a court in front of tens of thousands of people watching your every move, every call, with criticism.

The life of an NCAA official is not for the faint of heart.

Off the court, there were the rituals. Every referee had them, Boroski said. A "bizarre," planned-out regimen for being on the road five months a year. For Boroski, it meant 4 a.m. flights to land in the city where he would officiate that night, begging hotel clerks for early check-ins.

It meant dinner exactly three hours, to the minute, before tipoff. A 7 p.m. game often meant a Jimmy John's sub at 4 p.m., nothing too spicy that might mess with his stomach. "I was scared to death of getting food poisoning," Boroski said.

There was the physical toll. "We are basically making 85-foot sprints at least 150 per game," he said, averaging 3 1/2 miles each game. As a 6-4, former college baseball pitcher in his late 40s, Boroski knew more surgeries (he's had two on his knees) were in his future if he didn't call it quits.

There was the mental strain, dealing with "coaches who have huge egos and could run for governors in their own state and win in a landslide," Boroski said. They were imposing, often trying to intimidate, trying to see what they could get away with.

There were the superstars of college basketball rolling their eyes at him, the fans screaming in rage at him and there was the absolute, indescribable rush of being on the court.

Boroski never took any of it for granted, getting a free pass to witness some of college basketball's most historic games, getting to play a part in that history. Yes, there were negatives, but as Boroski says, "If you can't handle the crowd and if you can't handle the pressure, then you've got no chance."

Boroski could handle the crowd, the coaches and the pressure and he loved almost everything about his 20-plus years as a D-1 official, except for the last few years.

There was something he just couldn't get past, something he just couldn't settle in his heart – those five months out of the year he was away from his wife, Katie, away from his two boys, missing all kinds of special moments.

"I had lied to them for a long time. I had convinced them that everybody's dad left for five months at a time and came home for Christmas, then left again," Boroski said of his sons, who are 7 and 8. "They were on to me and it was absolutely killing me to miss their practices and their games."

After all, he had watched that vicariously with fellow officials through the years. "I remember questioning them, saying, 'Gosh you're missing your kid playing high school basketball? You've never seen a game and you only got to one last year? I'll never do that,'" Boroski said.

"And then I found myself in that position where I became that person I had criticized."

Boroski figured he had time to make good on his promise to be a "present dad." But that time had come crashing in on him as the 2022 Final Four ended. It was time to hang up his whistle.

"Most people in my situation," Boroski said, "wouldn't have walked away."

Text Gregg Doyel:Become a text buddy with Indy sports columnist Gregg Doyel

'It felt like somebody was tapping me on the shoulder'

Boroski had something else brewing, a business he had started in 2018. He is the founder and CEO of Indianapolis-based RefQuest, a company in the "officiating services space." RefQuest registers, educates, assigns and pays sports officials.

It just so happened in 2022, the NCAA was taking RFPs (requests for proposals) to hire a new officiating services provider, exactly what Boroski's company did.

"It felt like somebody was tapping me on the shoulder," Boroski said from his RefQuest offices last week, where Big Ten Championship basketballs and pieces of floor from Final Fours are displayed. "I just thought the stars aligned in that moment. I thought it went off like alarm bells, like this is an opportunity."

Boroski, who lives in Indianapolis, made a deal with his wife. "If I win this RFP and if I work the Final Four (in 2022), I'll sleep good at night. I'll retire."

On his way to New Orleans for the Final Four, Boroski got the call from the NCAA that RefQuest had been awarded the contract. And as he officiated the Duke vs. North Carolina game, he knew.

This would be his last game. His last of nearly 2,000 games he had officiated, where just about everything seemed magical. His last on-court memory to make – and there had been so many memories.

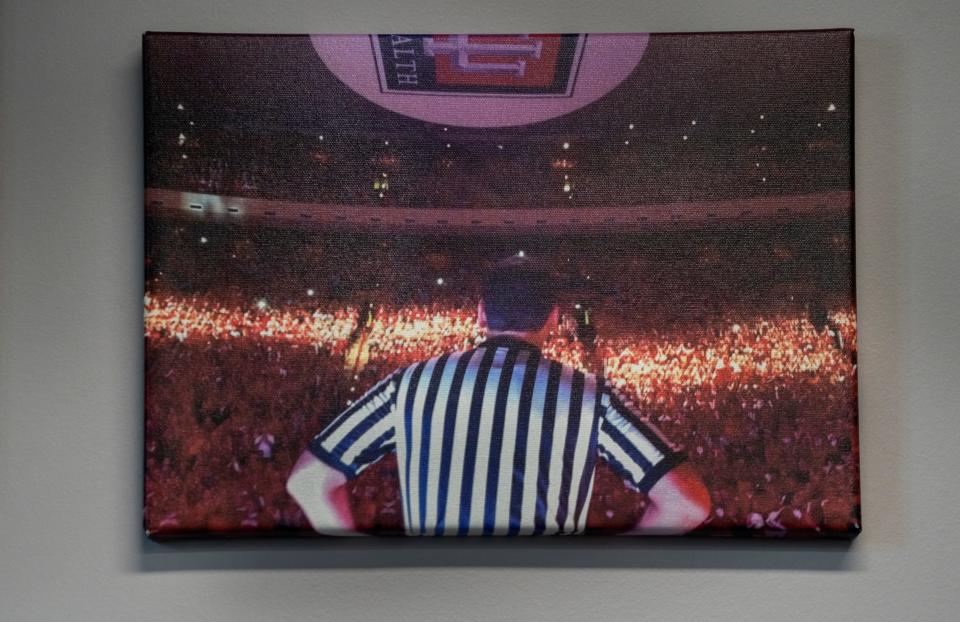

A photo hangs on RefQuest's office wall, Boroski shrouded by a sea of fans at Assembly Hall. A scorekeeper, a fellow official, took the photo at the December 2016 IU vs. North Carolina game at the ACC-Big Ten Challenge. "The place was insane," Boroski said. "How do you top that?"

He topped it with what Boroski calls his "No. 1 memory" in two decades of officiating, inside Madison Square Garden for the Big Ten championship in 2018.

Boroski is originally from the northeast, born in Freehold, N.J., less than 50 miles from the arena. But the Garden was always something his family couldn't get to, for one reason or another, finances mostly. "The Garden was always that place that other people went and I never got to go to," he said. "I didn't question it at the time because that's just the way it was. Some people get to do it and I wasn't one of those people."

Until 2018. "Now I was one of those people," Boroski said. "To be in the Garden for the Big Ten championship was something I'll never forget because that was mixing my past with my present."

Iowa coach Fran McCaffery remembers that tournament and an exchange he had with Boroski. "(Michigan coach John) Beilein was really giving it to him," McCaffery said in an email to IndyStar. "So I went up to (Bo) and said, 'He’s killing you way worse than when you ran me at Maryland.'"

Boroski had ejected McCaffery in Iowa's game at Maryland earlier that season. "His response to me?" McCaffery said. "'I hate it when you’re right.'"

That was the humor Boroski used, but the humor didn't always work. He also had to be tough.

"It's an adversarial relationship and we, as officials, have to find a way to take an adversarial relationship and make it work," said J.D. Collins, who officiated for two decades, including two Final Fours, an Elite Eight and five Sweet Sixteens. "We really don’t care if they like us but we really care if they respect us. If you worry about coaches liking you, you're going to lose the battle."

More from Dana:NCAA officials on reffing 7-4 Purdue star: ‘Zach Edey gets the living crap beat out of him’

Boroski said he always felt like coaches would push the limit, test boundaries.

"The coaches are going to do what you let them get away with. What goes unchecked is reinforced," he said. "You have to figure out how you let them be them and color inside the lines as established by the NCAA. That was not an easy dance."

Like the time Syracuse's Jim Boeheim came up to Boroski at the ACC-Big Ten Challenge playing Ohio State.

"Things were not going well for Syracuse, a couple calls, right or wrong, went against them and he made a comment to me. He said, 'You know Bo, I may just load up, put my team on the bus and leave."

Boroski had a retort. "I said, 'Well coach, my contract says that once the game starts, I get paid so if you want to leave and take your team with you it's fine with me. Just let me know what you want to do.'"

The exchange was half joking, half not. "And Boeheim looked at me as if to say, 'I can't believe you just said that to me,'" Boroski said. "Because I think for him it was supposed to be an act of intimidation." Boroski wasn't one to be intimidated.

Boroski had "tremendous feel" for the Big Ten coaches and players, said McCaffery. "His ability to communicate and manage the game made him one of the best officials in our profession. I’ve tried unsuccessfully, twice, to talk him out of retirement."

That's not happening, Boroski says.

"It was so perfect, the way it ended. I was able to say, 'I just did three straight Final Fours. My last game ever was Duke vs. North Carolina in New Orleans with a full house, post pandemic. My kids were there,'" he said. "If I would have said, 'One more year,' I could not have created a better ending to that chapter. I do think that chapter is over."

Road to the Final Four court

Craig "Bo" Boroski was born in Freehold, N.J., home to "The Boss" Bruce Springsteen. "Somewhere Bruce Springsteen is saying that he is from the same hometown as me," Boroski says, laughing.

When he was in second grade, the family moved to Tifton, Georgia. His mom was a nurse and his dad, Walter, the elder "Bo," a nickname for Boroski, was in the food business, which in the 1980s sent the family to live three hours south of Atlanta.

Boroski, the youngest sibling with an older brother and sister, came from a modest upbringing.

"I didn't know at the time that we grew up with not a lot of money because every penny my mom or dad made was spent on the kids," he said. "So we thought we were rich because we got anything we wanted, but what we wanted was a new helmet or new glove. We didn't want these over exorbitant things so we thought we had it all."

Growing up, Boroski loved sports and he played most of them, including basketball, until his senior year in high school when he decided to focus on baseball. He was a 6-4 pitcher and first baseman at Tift County High, a path he hoped would lead to college.

"Financially, from a family standpoint, if I wanted to go to college, I needed a scholarship," he said.

Boroski was good enough at baseball to get a scholarship, not a full ride, but enough to pay for college and play at the University of Alabama in Birmingham. He majored in criminal justice, but after college a torn rotator cuff meant surgery.

"I went into a bit of the doldrums where it was pretty close to loser status. There was no direction, no drive," he said. "I had no idea what I wanted to do. I knew I didn't want to have what I deemed a real job, 8 to 5 in an office. It just sounded miserable."

Then Boroski got the call from Lafayette, Indiana. A friend of his who ran a baseball academy had a 1-year-old son with a brain tumor. He needed Boroski to come up and help him run the academy so he could be with his son. The call came at 10 p.m., Boroski was on the road by 11 p.m. and he arrived in Indiana at 8 the next morning.

Boroski was helping a friend, but he was also helping himself. His life needed some direction.

He started giving private lessons to players and one of those players happened to have a dad named Tim Fogarty, who was a principal, coach and referee, who played the part in the movie "Hoosiers." The two hit it off.

Boroski had officiated youth basketball, baseball and soccer growing up. Fogarty encouraged him to go for a bigger reffing stage, to a college-level officiating camp in Evansville run by Eric Harmon.

"I went down there and got hired to officiate college basketball," Boroski said. "And the rest is history."

More from Dana:Maddox O'Connor was turned away by travel baseball teams. Then something magical happened

'It was a drug. I just loved it'

Boroski quickly moved up the ranks in the world of refereeing. Officiating coordinators were watching him, at first in small college games, at schools like Marian, Indiana Wesleyan and the University of St. Francis.

He had a map of the state laminated and put push pins into each school's location he would ref. "I was so into it," Boroski said. And he was good enough that he rapidly started moving up to bigger conferences. He went from five games a season to 15 games to 30 games. And by Year 3, Boroski got his big break.

Harmon had become a Division I officiating supervisor, what Boroski calls the "luck piece" of his career. He started giving Boroski a few D-1 games. His first was at Butler inside Hinkle Fieldhouse.

"I was hooked," Boroski said. His second D-1 game was at Ball State inside Worthen Arena. "And I'm thinking, 'My god, this is where I belong.' It was a drug. I just loved it."

Collins, already an established D-I official, met Boroski as he was breaking into the division. They started working a few games together and Collins saw the spark.

"He really had a desire to learn this," said Collins, who retired as the NCAA national coordinator of men's basketball officiating in 2022. "What stood out to me with Bo is what I called absorption rate. I never had to tell Bo twice."

Boroski explains a big part of his success on the court as understanding "art vs. science."

"The rulebooks say if the coach is out of the box and is yelling at an official, it's a technical foul. Well, I don't believe that to be true if they're one inch out of the box," he said. "Now what if they're six feet out of the box? Then yes."

"In any sport, the officials who are the most successful are the ones that understand both art and science and apply both," Boroski said. "It's hard to do and it creates critics of how you officiate. But that's there no matter what."

The critics. College basketball officiating is, arguably, one of the most thankless jobs. "You get it from every end," he said.

"You're part of a drama that's unfolding," Boroski said. And the three starring roles are the players, the coaches and the officials. "You have to go in to each game to be a willing communicator with everyone on the court. You have to have empathy and perspective. Why are they acting this way? If you can understand that, it's relatively easy to get through that drama."

It's been almost a year since Boroski left the court. These days, he watches college basketball at home with his sons.

And it's weird, he said, he hasn't felt any sadness or envy or regret as he watches those other officials making the same calls he used to make.

"Up to this point, I have not missed it one bit," Boroski said. "I do think March and April for the first week will be tough. Ask me on April 5 because as of right now ...."

As of right now, Boroski is good with the memories.

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Bo Boroski: Why NCAA referee quit after 3 straight Final Fours