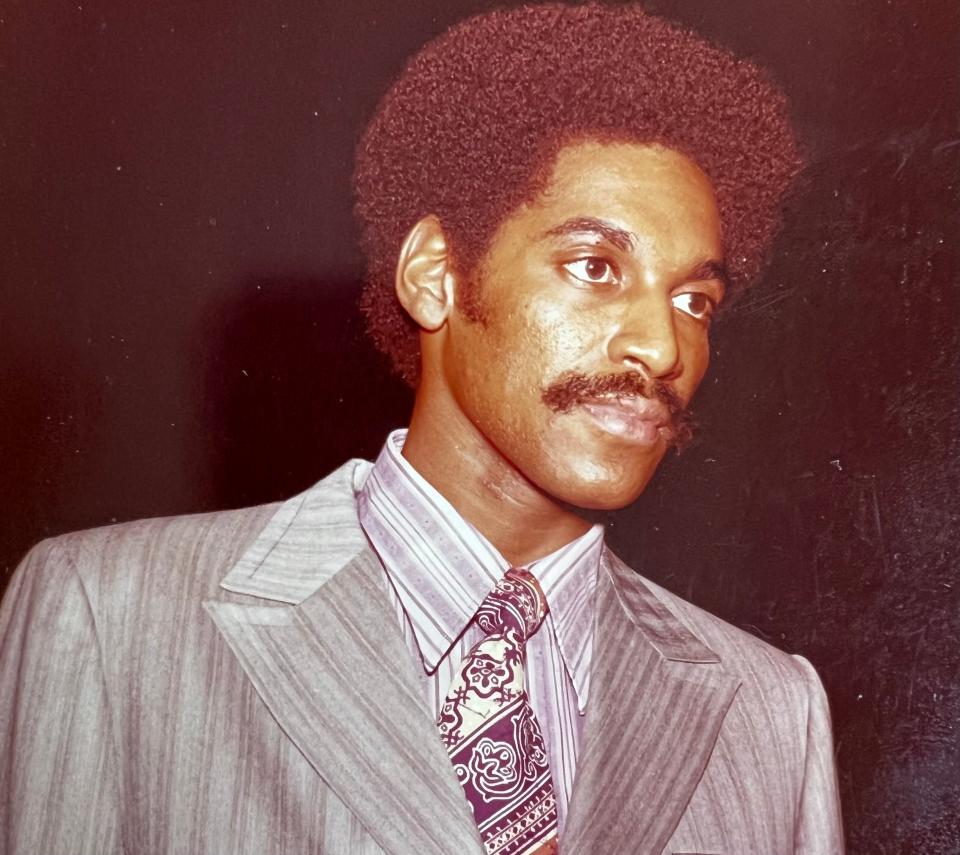

Roger Brown was Pacers superstar, city councilman and deputy coroner – at the same time

Editor's note: This story was originally published in 2023.

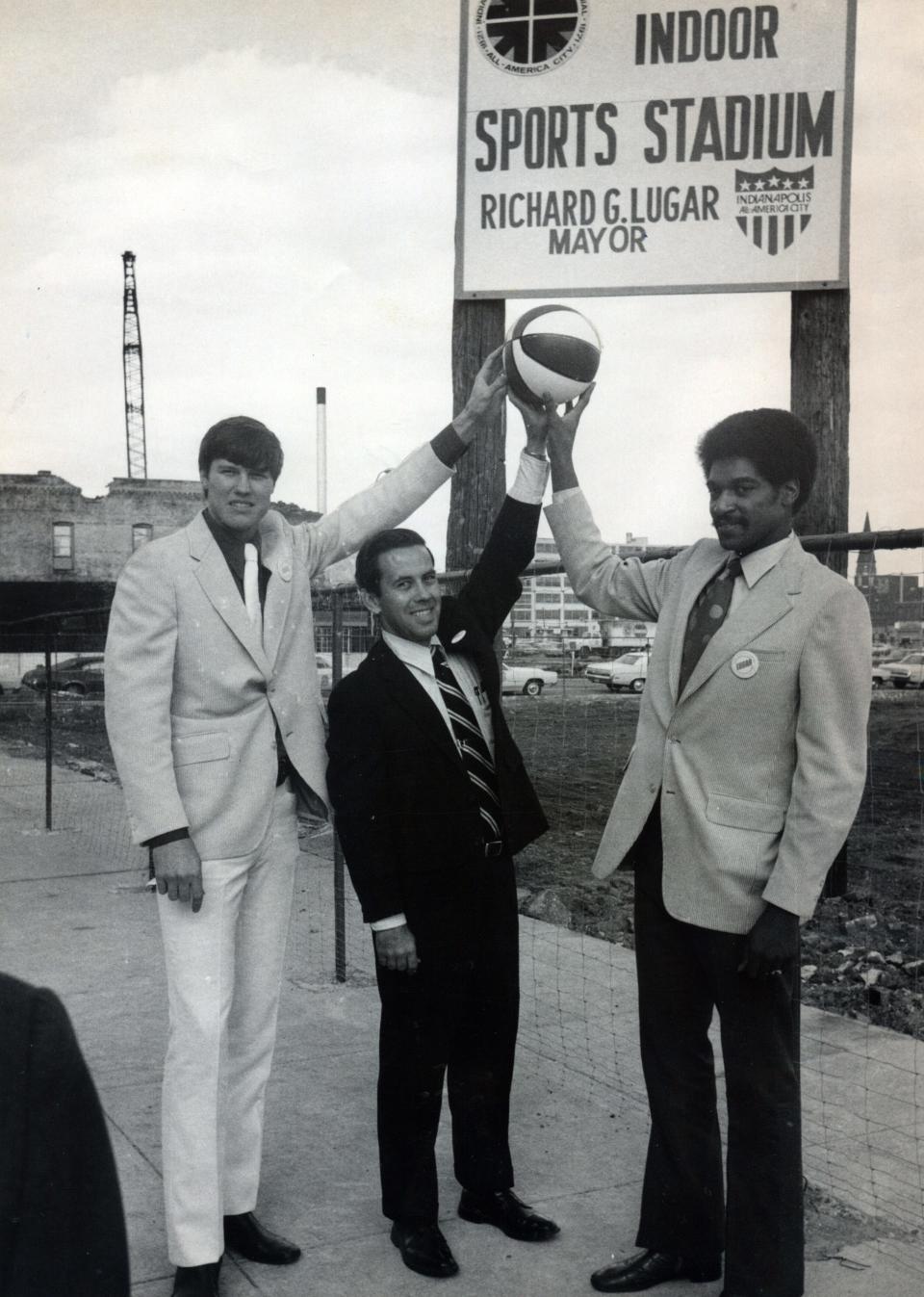

INDIANAPOLIS — As the polls closed throughout the city, and darkness fell on that crisp, clear night May 4, 1971, Roger Brown shook hands with Mayor Richard Lugar, slid into his Cadillac, shook his head and began his drive home.

All of this was crazy. Unreal. Kind of wild.

Brown was a professional basketball player, an ABA-All-Star for the Indiana Pacers who had led the team to a championship ring. Yet here he was driving home wondering if he might soon be a Republican Indianapolis City Councilman, the first pro athlete in the state to ever hold public office.

Brown's phone rang inside his Cadillac, startling him away from his musings. Yes, this at-large city councilman candidate had a phone in his car in 1971. The American Basketball Association didn't pay a fraction of what NBA stars make today, but Brown was financially comfortable, and he liked nice cars.

On the other end of the phone was a reporter from the Indianapolis News, who was calling to talk to Brown about his most recent victory. Brown's head began spinning inside his Cadillac. Was this about the game he had played a week ago against the Utah Stars? Or was this about tonight?

It was the latter. With 24,699 votes, Brown had secured a sweeping victory in the May primaries and his name would be on the ballot in November for at-large city councilman.

"I had hoped that we'd get a lot of votes in the primary," Brown, 29, told the reporter that night. "But I didn't expect to get as many as I did."

Brown had been campaigning for weeks on the streets, door-to-door, throughout neighborhoods in Indianapolis. "But most of my campaigning," he said that night, "was done earlier on the basketball floor."

In 1970, the year before he became a political candidate, Brown led the Pacers to an ABA title. He was named MVP of the ABA playoffs, scoring 53, 39, and 45 points in the final three games of the championship series.

The season leading up to Brown's bid for political office, he was named an ABA All-Star. It seemed the people of Indianapolis liked a candidate who could drain shots on the court and bring the city championship rings.

Brown always knew his basketball playing was an asset in his political endeavors, but he didn't think it was his only asset.

"People want a young mind, somebody that might get a few things done," he said in May 1971. "I feel that I can help people."

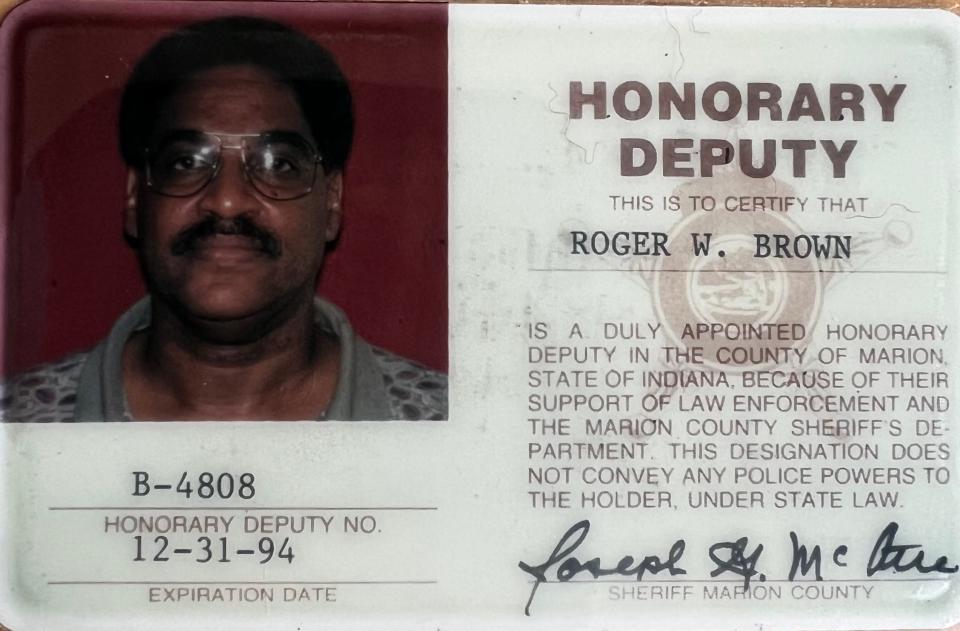

Brown went on to win the November elections. And as he pounded the basketball courts, he not only was a city councilman but a Marion County deputy coroner and sheriff's horse patrolman.

But just as Brown was always quiet and modest about his skills on the court, he was always quiet and modest about his life outside of basketball, said Pacers' teammate George McGinnis.

"He was a thinking man all the time," McGinnis said. "Roger wanted to be more than a basketball player, so he held all these positions while he played. I don't know how he did it."

'I want to help people'

Brown was never a political man, says his wife, Jeannie Brown, not the way politicians are thought of today. But he believed in helping others, and he believed in trying to make the world a better place.

One day, Brown's attorney came to him and suggested Brown run for political office. His attorney was a Republican, and there was an at-large city council seat up for grabs. Brown liked that idea. He liked the idea of making a difference.

After all, when Brown wasn't playing basketball, he would ride along on police patrols. "I had heard about how police supposedly mistreated people, so I decided I should get the other side of the story," Brown told IndyStar in 1971.

As he rode with the police, Brown met all kinds of people and "he picked up quite a following when citizens recognized him as one of the Pacers stars," IndyStar reported.

When Brown signed up for the 1971 city council ballot as an at-large candidate on the Republican ticket, he was backed not only by citizens but by powerful politicians.

"He has been very active, especially with the board of safety, and with our police during the last two years helping us in a number of very difficult situations," Lugar told IndyStar in March 1971. "I had actually considered Roger Brown for the board of safety on the basis of his interest, and then found he had interest in becoming a candidate. I encourage this. I am very grateful he will be on our team."

As he campaigned, Brown talked about growing up in poverty in Brooklyn and how he understood the struggles of the unemployed. He said he knew the discrimination of being a Black man. And he understood now, as a basketball star, what it meant to be privileged.

"There is no color line as far as I am concerned," Brown said in 1971. "What is good for one is good for all, and I want to help all of the people in whatever way I can. I haven't been a pro basketball player all my life, you know, but now that I've got mine, I want to help people get theirs."

'An old soul': High school hoops phenom is grandson of ABA Pacers Hall of Famer Roger Brown

'He loved serving others'

Brown was born May 22, 1942, in Brooklyn, an underprivileged boy who not only became a basketball star at Wingate High School but one of the greatest players in New York City preps history.

In 1960, the University of Dayton signed Brown to play, and he starred as a freshman. But a year later, he was implicated in a gambling scandal. It was alleged notorious gambler Jack Molinas had tried to get Brown, while he played in high school, to introduce him to college players who would fix games.

Brown was never found guilty of doing anything illegal, yet he was forced to leave Dayton, was banned by the NCAA and the NBA. He started playing in amateur leagues in Dayton at night while working at a General Motors plant during the day.

It seemed the controversy had ended Brown's basketball career until the Pacers, part of the newly founded ABA, took Brown as their first player on the advice of Oscar Robertson, who grew up in Indianapolis.

The Pacers never regretted that.

During his eight years with the Pacers, Brown led the team to eight ABA playoff appearances, five division championships, and three ABA championships. He averaged 18 points, 6.5 rebounds, and 4 assists per game, and scored his all-time high of 53 points in Game 4 of the 1970 ABA finals.

Former Pacers great Reggie Miller once called Brown “the greatest player to never play in the NBA.” Selected unanimously to the ABA All-Time Team, Brown was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in September 2013.

And yet, as Brown played, he was more than a basketball star. He was the first pro athlete to hold public office, serving on the Indianapolis City Council from 1972-1976.

Of course, there were some logistics that didn't always work out. There were plenty of council meetings Brown couldn't attend. He was on the road a lot playing basketball, after all. Fellow council members would place a basketball in his empty seat when he couldn't be there, said Jeannie Brown.

When he became a deputy coroner, Brown would come home from a game late at night, go to bed, only to be awakened by a call. Someone had died and Brown needed to be there.

"He loved serving others," said Jeannie Brown.

In addition to being a Pacers star, city councilman and deputy coroner, Brown was also a member of the sheriff's horse patrol, along with teammate Mel Daniels.

When Brown died in 1997 after a battle with colon cancer, his funeral procession was led to the cemetery by the sheriff's horse patrol, including Daniels.

Brown was always a man of the people, said Jeannie Brown. Even after his playing days, he served in many roles, including being named a Marion County Sheriff's honorary deputy.

"He just wanted to make a difference," she said. "Whether it was on the court or politically. He just loved being a part of making a change."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: As Pacers superstar Roger Brown played, he was also city councilman