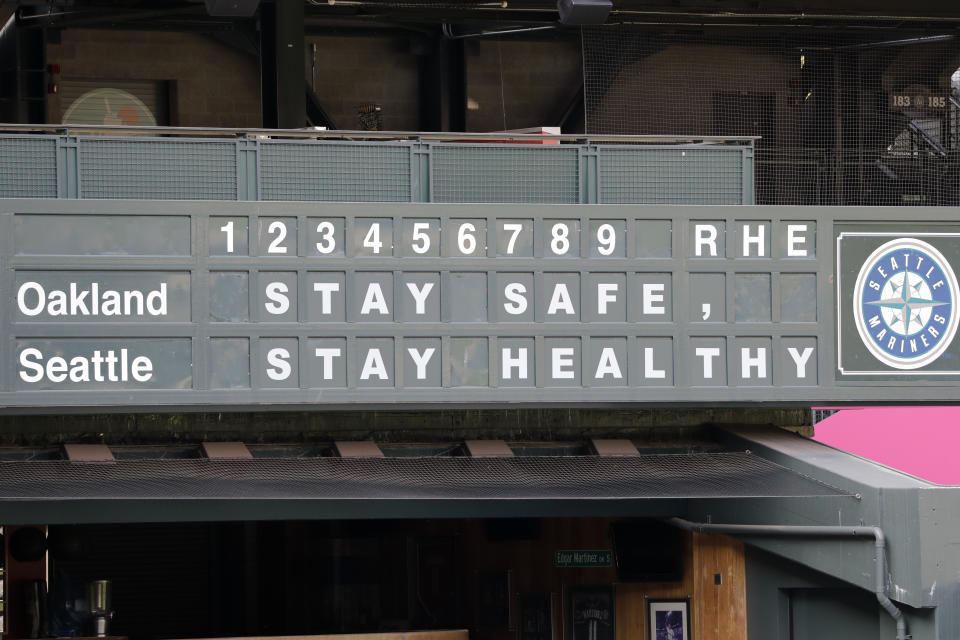

What MLB should have learned from America's botched pandemic response, but didn't

Frankly I am not sure what about the past five months in America would make you think that simply asking people to stay safe is a sufficient pandemic management strategy. Especially if you’re also mandating that they go to work and travel around the country.

After outbreaks on two Major League Baseball teams, the Miami Marlins and the St. Louis Cardinals, disrupted 20 percent of the league’s teams in the first week and a half of the 2020 season, commissioner Rob Manfred said that “the players need to be better.” He levied a public threat through the Players Association chief Tony Clark that the season itself was in jeopardy. He told the Associated Press that the solution is “peer pressure” and “players taking personal responsibility.” (He also said, “it's us managing more aggressively.”)

But the failure to protect players from their most imperfect impulses, and the season from the players themselves, is a failure of protocols and the people who designed them. Or at the very least, neglecting to account for those inevitable infractions certainly is.

It doesn’t really matter if you think that amounts to a coddling of adult men with ample financial motivation to exercise an abundance of caution (assuming their health and that of anyone they might come in contact with wasn’t compelling enough). Because having someone — or even an entire collective bargaining unit — to blame isn’t actually as good as having a baseball season. If I were responsible for the viability of a many billion-dollar industry, I would probably do a Google about whether large groups of people are reliably good at individual risk assessment and following recommendations to a tee before I made that the foundation of my plan.

“If your system only works with extraordinarily high levels of compliance, then it's on leadership to create the environment in which compliance is likely,” said Dr. Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, a University of Pennsylvania law school professor who studies the psychology of moral decision-making.

Wilkinson-Ryan is not an epidemiologist, but she has written for The Atlantic about how America’s reopening strategy, despite soaring COVID cases, ignores expert understanding on cognitive biases — effectively creating “a psychological morass, a setup for defeat that will be easy to blame on irresponsible individuals while culpable institutions evade scrutiny.”

It is a tautology to say that the actions of certain players compromised the young season. Whether it’s helping a little old lady cross the street or going to a strip club, the way to catch the coronavirus is by being a person who does things out in the world. Players do things. Abstract policies don’t.

That makes it harder to pin failure on the people responsible for the policies — who are neither assuming the same level of risk nor as individually impactful in their failure to mitigate that risk. Just because you can trace the outbreak back to a particular player’s behavior doesn’t mean the failure isn’t at the institutional level.

It is disappointing, but not surprising, that among hundreds of players, some of them would engage in unacceptably risky behavior.

MLB’s operations manual says that the league will not dictate players’ behavior away from the ballpark, while living in their home communities (of variable coronavirus saturation). Instead, they’re expected to “avoid situations in which the risk of contracting the virus is elevated” and “act responsibly.” From there, it’s left up to the individual teams to establish more explicit guidelines. The league meanwhile, “will not be involved in the crafting or enforcement of any of these team-specific codes of conduct.”

This kind of disjointed, ad hoc response in which people are advised to not patronize legally open establishments, and the safety of a large group is dependent on the variable self-restraint and decentralized risk assessment of individuals, mirrors the broader response to COVID-19 in America.

That is literally why there is still a raging pandemic.

A league investigation reportedly found that the risky behavior among the Marlins was not — as had been irresponsibly speculated — going out to a crowded bar in Atlanta, but rather gathering with teammates in a hotel or sitting close to one another on a plane.

“If that’s how it’s being transmitted, then yeah, maybe you can’t open up how you want to,” Wilkinson-Ryan said.

“If what you're requiring is people to know where to be and how to be next to each other or not next to each other all day long, that is really tough. And so that requires a huge amount of coordination from the top.”

That means clear, definitive mandates — where right now wearing masks in the dugout is merely a recommendation and teams are told they “should consider” facilitating outdoor dining. It also means providing what Wilkinson-Ryan termed “affirmative ways to facilitate” predictable behavior. In other words, tell players they should socialize outdoors instead of in hotels rooms rather than assuming they’ll stay completely isolated while on the road.

The league and the MLBPA are reportedly in the process of negotiating an update to the existing operations manual to incorporate lessons learned the hard way so far this season. Perhaps those changes will make it easier for players to protect themselves and, by extension, their teammates and the league at large. But we should be careful to hold the correct people accountable for the failures thus far.

“What would happen if you told people to just use their best judgment about how fast they go on the highway?” Wilkinson-Ryan said by way of example. “You would just never do that because you know that even a little bit of non-compliance is really dangerous.”

Even people making good-faith judgment calls can compromise the season by erring ever so slightly on the wrong side of the safety line. This isn’t to say that players aren’t culpable for egregious infractions — in-game footage has routinely captured prohibited behavior like spitting — but, if anything, that’s a testament to how unreliable unenforced guidelines are.

By opting not to isolate their players in a bubble — or else reasonably deciding it was not feasible to do so — MLB shifted the onus of safety onto the individuals themselves. That decision simultaneously exposed the players to the same rate of risk, whenever they’re away from the ballpark, that exists in a society where 1,000 people are dying from COVID-19 and another 60,000 are testing positive, on average, every day.

Especially without an explicit plan for how to contain an outbreak like what the Marlins experienced, that was never going to work — no matter how sternly the commissioner chides his players.

“What you're describing to me does not sound like it's feasible,” Wilkinson-Ryan said of the level of exposure inherent in traveling. “I mean, that would basically require everyone to have perfect hospital-grade compliance. And if that's what they want, then they kind of have to have hospital-grade spaces.”

More from Yahoo Sports: