The Premier League has a VAR crisis. The NFL has a solution

VAR, in theory, sounded great. It really did.

But a few years after soccer’s first widespread video review system debuted, it has become clear that VAR is not great. It’s harming the sport. Injecting itself unnecessarily to suck away joy. Changing outcomes that literally nobody felt needed to change.

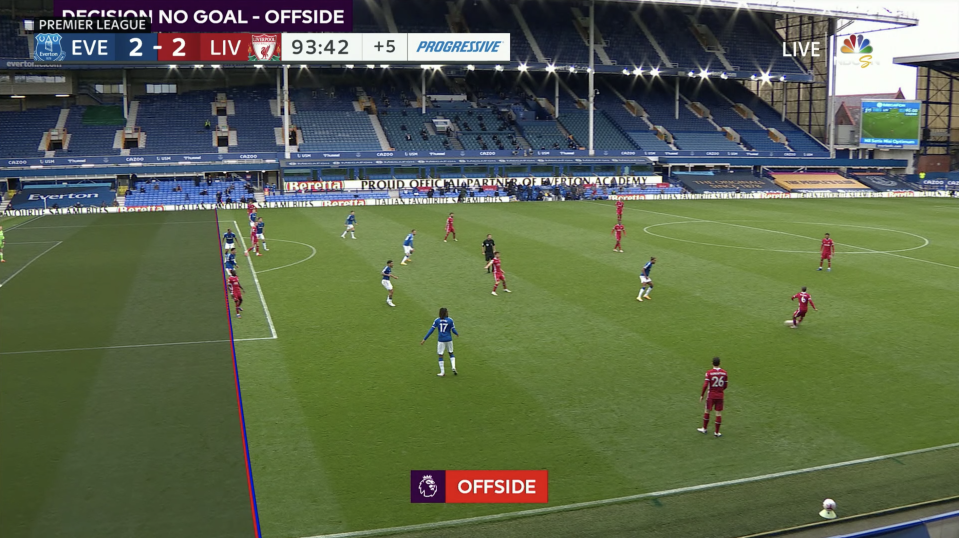

On Saturday, it turned a brilliant Merseyside Derby into a postgame moan-fest. Jordan Henderson won the match for Liverpool. Then he didn’t, because apparently Sadio Mane’s shoulder was one inch too far forward in the buildup to the goal.

The Video Assistant Referee system has overstepped its bounds. It was put in place to correct “clear and obvious errors,” which it does. It has also reversed marginal, previously undetectable errors-that-aren’t-really-errors, like the phantom offside that disallowed Wolves’ equalizer against Liverpool last year ...

... and the eerily similar call that disallowed Henderson’s winner against this year.

VAR, like so many other great ideas, came bearing unintended consequences. The issue isn’t just the offsides and handballs that are anything but “clear and obvious.” It’s the hesitation that now accompanies every goal because of them. It’s the unspoken fear that ecstatic celebrations will, two minutes later, seem embarrassing; that the most instantaneous and genuine of emotions can be undone.

Something has to change. The difficult part is figuring out what, and how. Because the simple solutions also bear unintended consequences. VAR, therefore, needs an overhaul.

Why the offside problem can’t be fixed

The first issue with Saturday’s Liverpool-Everton decision is that it’s unclear whether Mane was actually offside. Because, for all the technology that enables VAR, it still requires a human to make a very subjective and difficult decision: Where, underneath Mane’s sleeve, does his arm – which is irrelevant for offside purposes – end and his shoulder begin?

The video assistant isn’t some expert on Mane’s anatomy. He doesn’t have X-ray images at his disposal. Offside is supposedly factually, which is why decisions don’t have to be “clearly and obviously” wrong to be overturned. But there’s significant room for human error here. Enough that an incorrectly-drawn line could ruin a perfectly good goal.

1. How are we trusting a human to look at a screen and point to the exact spot that Sadio Mane’s shoulder becomes his arm?

2. How are we picking out the exact moment when Thiago plays the ball? (There isn’t one exact moment)

3. How to fix VAR: https://t.co/9pJjhqaW3w pic.twitter.com/WQ04vLcOCU— Henry Bushnell (@HenryBushnell) October 17, 2020

One solution would be to account for that margin of error. Tweak the rule so that there must be, say, three inches between the attacking line and defensive line to overturn a call.

The problem with any fix specifically targeting offside decisions, however, is that line-drawing is necessary no matter the law. Another common proposal is that offside should require “daylight” between infringing attacker and last defender. But who decides what constitutes “daylight”?

No matter where you draw the line, there are imperfections and marginal decisions that must be made. There would be fury on the margins of a three-inch buffer, just like there is fury with no buffer.

Neither the offside law nor its application is the problem. Nor is scrapping VAR altogether the answer, because we do want “clear and obvious” errors corrected.

The solution is to leave the laws intact, and devise a different system for deciding what’s “clear and obvious.”

How an NFL-style challenge system could work in soccer

Fortunately, the NFL has already devised that system. It’s called the coaches challenge system. It takes responsibility away from off-site video assistants and hands it to the aggrieved teams themselves. Because who better to decide what’s “clear and obvious” than the managers who believe they’ve been clearly and obviously wronged?

Here, in short, is how and why a challenge system would work in soccer:

• Limits on challenges: Each coach would have one challenge per game. One opportunity to trigger a review. If the review yields an overturned call, the coach gets a second and final challenge. But that’s the cap. A second success doesn’t earn the coach a third.

This will significantly reduce the amount of time spent waiting on VARs, not only because it introduces a maximum of four reviews per game, but because it forces coaches to be prudent rather than reckless with their challenges. They can’t just reflexively call for a review of a first-half goal, because if they’re wrong, they have no recourse for the second-half decision that is clearly and obviously wrong.

• Statute of limitations: A coach must challenge a call within 10 seconds of the incident in question. Once 10 seconds have elapsed without a challenge, the call stands (and, if the incident in question is a goal, celebrations can continue unhinged.) This prevents teams from scouring dozens of replay angles in search of a possible infraction to challenge. It has to be “clear and obvious” in real time.

• The mechanics of the challenge: Coaches trigger a review by going to the fourth official in that 10-second window. If there’s a worry that coaches don’t have proper vantage points to detect clear and obvious errors in real time, allow them to communicate, via headset or earpiece, with an assistant watching a live video feed. Also, give the captain challenge power. Just as the manager can go to the fourth official, the captain can go to the on-field referee.

• Everything is challengeable: Rather than limiting reviewability to goals, penalties and red cards, expand it to every aspect of the game. All fouls, yellow cards, corners, and so on.

At first, this sounds dangerous … but the challenge system remains the great regulator. Coaches would never challenge a foul at midfield in the first half, no matter how clearly and obviously wrong the call is. But if there’s a questionable tackle just outside the box in the 90th minute, they should be able to challenge it. It’s up to them to decide not only what is “clear and obvious,” but what is impactful enough in the grander scheme of the game.

• Challenges during open play: If a coach wants to challenge a no-call and play is ongoing, the 10-second window for challenges still applies, BUT the review doesn’t occur until the next stoppage in play.

• Time limits on reviews: Once a review begins, the referee jogs over to a pitchside monitor. Once he gets there, he and the Video Assistant Referee have 60 seconds to make a decision. If the evidence they see in those 60 seconds convinces them the call on the field was wrong, they overturn it. If not, they leave it as is.

The time limit essentially serves as the “clear and obvious” threshold. If offside is in question, and intricate lines from grass to shoulder are necessary because nothing about the play was “clear and obvious,” the refs won’t have enough time for definitive conclusions.

What a challenge system would look like in practice

Let’s retrospectively consider Saturday’s Merseyside Derby as a test case. The first controversial incident came in the first half, when Jordan Pickford clattered into Virgil van Dijk and probably should have been sent off. There was no call on the field. If Jurgen Klopp immediately felt there should have been, he could have used a challenge. It probably would have been successful. Pickford would have been shown a red card, and Klopp would have been awarded a second challenge to use at some point throughout the rest of the game.

Or perhaps Klopp doesn’t challenge the Pickford-van Dijk incident, and the game plays out as it did in reality.

In the second half, Everton manager Carlo Ancelotti could have challenged a 59th-minute incident when Richarlison appeared to be tugged ever so slightly by Trent Alexander-Arnold while pursuing a cross. He also could have challenged Richarlison’s 90th-minute red card, which Everton players initially protested. Ancelotti might have been right about the first. He would have been wrong about the second. He wouldn’t have had a challenge remaining to contest Henderson’s winner. And absolutely nobody would be complaining that Mane was offside.

The system is far from perfect. There will be instances, inevitably, when a late call costs a team points because a coach, having exhausted his or her challenges, can do nothing about it. But that happens far more often without VAR. And more often than not, those coaches would only have themselves to blame for a faulty or less significant challenge earlier in the game.

There will also be times when a coach does have a challenge remaining, and uses it on a late winner even though he or she sees nothing wrong, and lucks into an overturn. That, admittedly, could have been Ancelotti on Saturday if he’d held off on earlier calls. But that will be rare, far more rare than the ridiculous VAR decisions that have plagued the Premier League.

The challenge system is the best of both worlds. It retains the flow of the game. It gets rid of the looming, inescapable uncertainty that currently pollutes every key moment of every game. But it still corrects the blatant errors – as long as coaches challenge responsibly.

More from Yahoo Sports: