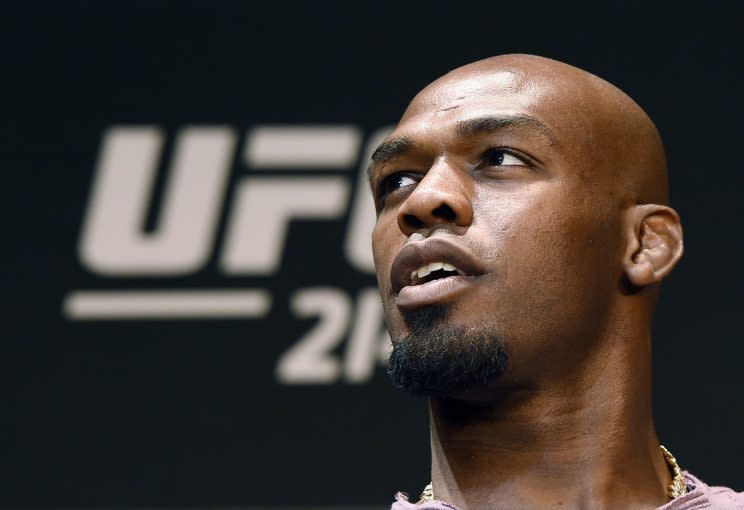

Can Jon Jones stop killing his own career?

Whether through counseling or common sense, Jon Jones is trying to not care what everyone says about him. This is wise. Public perception has proven to be his first unwinnable fight. So he seeks the bright side.

It’s “a freeing feeling to be looked at as a piece of [expletive] by so many people,” Jones said this week.

Saturday, at UFC 214 in Anaheim, California, Jones is scheduled to make his long-awaited return to the Octagon for his even longer-awaited rematch with light heavyweight champion Daniel Cormier. Peace of mind is essential.

In truth, this is a work in progress. Jones, 30, wasn’t born with the gene to blast through life without concern for outside opinion. He may act that way on occasion. He may verbalize it, as he often has this week. It isn’t his nature, though. He clearly cares.

Just the other day, for instance, Jones was watching one of the company-generated promotional videos for UFC 214.

Across the screen came a clip from an interview from 2011, when Jones was still the ascending, fresh-faced, youngest UFC champion ever. He was the future, the kind of athlete and breakout personality who could push the sport into the mainstream.

“[I said] I never wanted to do anything to harm the image of the sport,” Jones recalled.

Jones, of course, has done plenty of that, although most of the damage was to his own image.

He was once a marketer’s dream, A 6-foot-4 son of a pastor from Endicott, New York, who by his mid-20s was so ferocious that he was deemed the greatest UFC fighter of all time. The middle of three brothers, the other two are Super Bowl champions (Arthur in Baltimore, Chandler in New England). A big-smile kid with a knack for feel-good stories – for instance, hours before winning the UFC light heavyweight championship in Newark in 2011, he chased down a mugger on the street and subdued him until the cops arrived.

He soon had a Nike deal. He should’ve been a massive commercial star, the Michael Jordan of MMA.

These days he’s known as much for multiple suspensions (he’s fought once in 30 months), having his belt stripped (twice), cocaine use, marijuana pipes, relentless partying, a DUI, a probation violation, a brief jail stint, a hit-and-run that broke the arm of a pregnant woman, and blowing up the historic UFC 200 card (and a fight with Cormier) due to a failed drug test over a sexual-enhancement pill. That netted him excessive humiliation, relentless teasing and a year suspension that just ended earlier this month.

Somewhere in there, Nike and nearly everyone else bailed.

Perhaps worst of all, he stopped being Jon Jones. He was talented enough to coast through personal trials. He never lost. His 23-1 record is blemished only by a 2009 disqualification for illegal elbows as he was handing out a hellacious beating. He wasn’t quite the same, though. He hasn’t finished anyone in more than four years and has rarely done much of anything of late.

So along came the scorn. Jones needed a plan to deal with it. Except, despite proclaiming to embrace the hate, the promo clip stung, maybe in ways Jones wasn’t expecting.

Part of it was seeing a younger version of himself – full of hope and possibilities, unstained by scandal or shame. Who is that kid? Six years ago must’ve felt like 60. Part of it was how the quote was framed, his once-earnest words coming across like it was all just empty talk, like he was nothing but a fraud from the start.

“I was uncomfortable with it,” Jones said of the clip. “… That was genuine man, I never intended having the image of a bad guy. I really didn’t.”

He sort of sighed. He’s got a long way to go with this part of his rehab. He just knows he needs to find a way to shrug off Cormier calling him “a junkie,” or fans mocking him for literally giving away his belt, or the media harping on this or that.

“[Expletive] it and just call me the bad guy,” he said Monday.

Yet in the next breath he is leaning on motivational clichés to remind people, if not himself, to give him another chance.

“We are not our past,” Jones said. “We are not our mistakes. Our story is not over.”

Neither side of Jones is wrong, it’s just the internal wrestling match one of the sport’s best wrestlers is engaged in. The truth for Jones, like nearly everyone, has always rested in the middle – neither a pure angel nor a true villain.

“Somewhere along the way I got lost, man,” Jones said. “Somewhere along the way I stopped caring. And I started living for myself. … And I got caught up in my own [expletive], and having fun and partying and still winning. I just took it all for granted. I mean, I genuinely wanted to be an inspiration to other people and inspire people and be a role model. That was my original thought.”

UFC 200 in July 2016 was perhaps the most emotionally disappointing. He handed Cormier his only defeat in January 2015, but after Jones was stripped of the title for the hit-and-run accident, it was Cormier who wound up with the belt, mocking him all the way.

Jones swore he had turned the corner and was eager to take back what was his. Yet here he was, unable to fight for taking a pill that even USADA acknowledged wasn’t designed to gain him an advantage inside the cage. That didn’t take away the positive test, the cancelled fight or the long suspension.

Suddenly, Cormier and everyone else could call him a drug cheat and cast aspirations on the one previously undisputed part of his life – his domination. And once again it was Jones who was unstable and unreliable.

“People didn’t see what I had done to get back to that point,” Jones said of UFC 200. “I mean, things got really ugly for me with the lawsuits, the probation, the court stuff. It was so ugly. The hit that my image [took]. The situation I put the girl in, it was terrible. It was terrible. And it took me a long time and a lot of effort to get back.

“And then … I tainted my legacy because of an estrogen blocker. To delegitimize all of that to label me a steroid cheat?”

He was back to caring about the opinion of others. Saturday, he said, will change everything.

“It’s a really, really big fight for my legacy,” Jones said. “[It’s a chance] for people to remember why I’m an exciting fighter. I think people have forgotten about the things that make me special.”

Maybe they have. Or maybe they want him to prove it again. Or maybe they’ve just tired of the soap opera. The man was unstoppable … at least until he stopped himself.

It was all there in that promotional video, Jones acknowledged. There were as many crash scenes and perp walks and teary-eyed news conferences as vicious elbows or victorious moments. It was all there for the world to see, his worst moment used to sell a fight.

For Jon Jones, it was an unexpected reminder of what he once was, what he lost along the way and what, at age 30, there is left to be reclaimed.

Yeah, it hurt. But hurt can be good.

“The promo,” Jones concluded, “was honest.”