Three things we're not talking about enough ahead of UFC 244

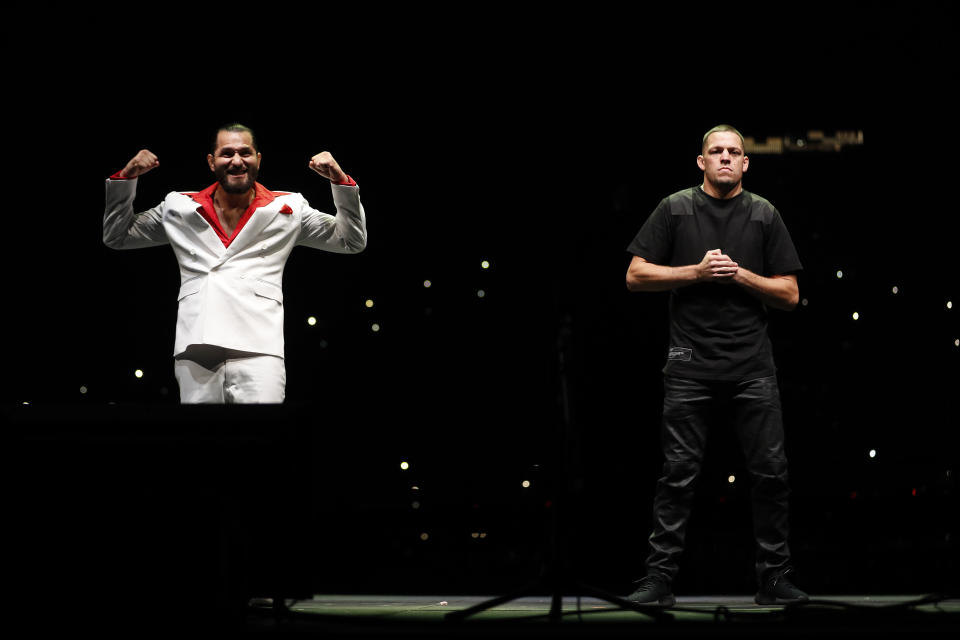

Count this writer as among those unquestionably happy that UFC 244’s main event between Nate Diaz and Jorge Masvidal was made, and is still on. These two perennial contenders have built loyal and sizable fan bases over their long careers despite often being marginalized by powers that be and now they’re headlining the year’s biggest show.

Diaz vs. Masvidal has the combat sports world buzzing and doing so only on the strength of their skills and charisma. The bout needed no trash talk or disrespect to build it, and each man has done nothing but compliment the other while still promising violence.

As far as these things go, it’s a beautiful thing to behold. So, celebrate it, tune in and let’s enjoy. I certainly will.

Still, there are important items that are not being discussed enough this week surrounding the bout. Here are three ideas we’re not talking about nearly enough ahead of UFC 244:

1. Making the BMF title ‘official’ makes it less cool

When Diaz called for a fight with Masvidal after beating Anthony Pettis and “Gamebred” immediately nodded his approval from ringside it felt organic and exciting. Diaz said that he and Masvidal were “gangsters” and didn’t need any company title or championship to prove their worth.

Then, the UFC quickly jumped on Diaz’s “Baddest Mother[expletive] in the game” concept, and decided to create a physical belt for the title. We quickly went from two confident anti-heroes agreeing to fight one another out of mutual respect for a symbolic title that represented how they did not and could not be understood within “official” parameters, to them fighting for a corporate-approved and designed belt that will be placed around the winner’s waist by a wrestler-turned-movie star.

It’s a classic example of a dominant culture adjusting itself to remain relevant by co-opting and incorporating an emergent culture. The point is that Diaz and Masvidal fighting each other is still dope, but the belt they’re fighting for is corny.

2. The wrong people will profit most from the BMF title

The title of Baddest Mother[expletive] in the game — Nate Diaz publicly invented it, in this context, but it’s the UFC that is licensing it. That means it will oversee its use, how it is profited from and decide how all those profits from the idea are divided up instead of the talent who created the concept and who will fight it out doing so. Of course, this is nothing new in many ways.

UFC athletes already get less money as a percentage of revenue than other major sports athletes in the NFL, NBA, MLB and NHL. The UFC’s new ownership, with its eagerness to profit off of intellectual property that they claim they own, including fighters’ names and likenesses — in perpetuity — as well as its double-dipping of promoting and managing certain fighters as agents (something which is illegal in boxing) will likely only make things worse for athletes in this regard.

Diaz has not been shy over the years in criticizing the UFC and its pay and benefits for athletes. It isn’t hard to imagine that one day he’ll eventually add his coming up with a concept like a BMF title, then having it branded and monetized without his being in control of its usage or having royalties for its use being set by him to his long list of things he’s upset at the company for.

3. UFC’s drug-testing system is structurally flawed

Sure, in the short-term it is great that Diaz is still fighting Saturday after a scare where he says he was told he failed a UFC/USADA drug test and was asked to keep it quiet, fight and deal with the aftermath, later. Diaz leveraging his popularity and powerful position is what got and kept him in the fight, however, not the murky system of effective self-regulation the UFC has with regards to drug testing its athletes.

The fact that Diaz and Masvidal are still fighting doesn’t resolve any of the deeper problems in that system. To be clear, the UFC pays USADA.

The testing group likes to call itself “independent” in its releases and marketing materials, but it is not. Structurally, it works for paying clients.

The UFC hired USADA and can fire them. This creates a structural conflict of interest if independent oversight of drug-testing protocols is the intended goal.

State athletic commissions also test UFC athletes, but usually far less than the UFC/USADA tests them. They are independent, technically. There is still a troubling amount of interdependence between promoters and athletic commissions, however, and commissions are often cash-strapped, which leaves open the door to the UFC and other promotions sometimes effectively self-regulating themselves on a host of issues.

It used to be that state commissions were the only ones who tested UFC athletes for banned substances. A few years ago, however, the UFC took the bulk of testing of its athletes into its own hands by hiring USADA.

USADA’s supposed rules and protocols can and have subsequently been disregarded on occasions when they got in the way of the UFC booking big fights when they wanted them. This happened with Brock Lesnar before UFC 200, and he then proceeded to bludgeon Mark Hunt while hopped up on performance-enhancing drugs.

The UFC and USADA’s rules are also often troublingly fluid, and the process for determining those rules is done away from public view, as just happened with Diaz. We’re only told by the UFC what supposedly happened after Diaz blew the whistle.

We’re told that rules were already changed, or about to be, or were sort of agreed upon in principle, and we were told that it matters if a fighter intended to take a banned substance or not. Well, sometimes, but not always, which is something that wasn’t the case a few years ago when commissions like Nevada’s did not show much mercy at all to the tainted-supplement defense.

We’re not told why, though, and we’re not told who the experts are who were able to determine that Diaz didn’t “cheat” even though he tested positive for banned substances. It’s similar to the way we’re told that Jon Jones didn’t “cheat” for the banned substance repeatedly found in his system which we’re also told may always stay in his system so, you know, just expect him to continue to test positive and be alright with that. We’re also not told why Diaz’s case was able to be resolved so quickly, and by who, exactly, despite the fact that fighters like Neil Magny were told there was not enough time to get to the bottom of their cases and were pulled from fights.

The UFC/USADA investigations and disciplinary processes are done behind closed doors and not subject to the same level of inquiry from journalists as state commission ones which are public proceedings. So, the UFC/USADA processes are opaque.

Fighters have been suspended for supposed violations without the public knowing, after investigations and hearings conducted in secret, and then put on the shelf for a long time behind closed doors. Diaz’s case may have ended the way most of us desired, but it still happened in the dark without much explanation of what occurred and why.

Fighters not as powerful as Diaz have missed fights and paydays that their families depend on when in a similar position as the one Diaz so quickly resolved by speaking out. We were told, then, that there wasn’t enough time to get to the truth in time for their fights to happen.

This time we were told that there somehow was enough time and that unnamed experts deemed Diaz to not be a cheater despite his having banned substances in his system.

Big name fighters like Lesnar, Jones and Diaz get to circumvent the mushy rules or have them interpreted through non-accessible processes in their favor or have their cases expedited while other fighters don’t.

That has everything to do with exercises in power and nothing to do with fairness or caring about athlete wellness.

More from Yahoo Sports: