The reinvention of Randall Cunningham

The first chords flutter a little after 8 a.m. A keyboardist and guitarist lead the way. Harmonizing voices warm. Spotlights brighten. And on a gorgeous winter morning in Las Vegas, inside the nondescript beige building at 325 East Windmill Lane, souls begin to stir.

It’s the third Sunday of January. Roads are empty. Most of Vegas sleeps. But here, four miles south of The Strip, two parking lots fill. Around 150 people stream into Remnant Ministries. Gospel music fills their ears. An elder white woman closes her eyes and spreads her arms. An elder Black woman kneels and tilts her chin toward heaven. A scruffy man rests his arms on a protruding belly and sways, side-to-side, peacefully.

They all sing:

“I am a friend of God. I am a friend of God, He calls me frieeeend.”

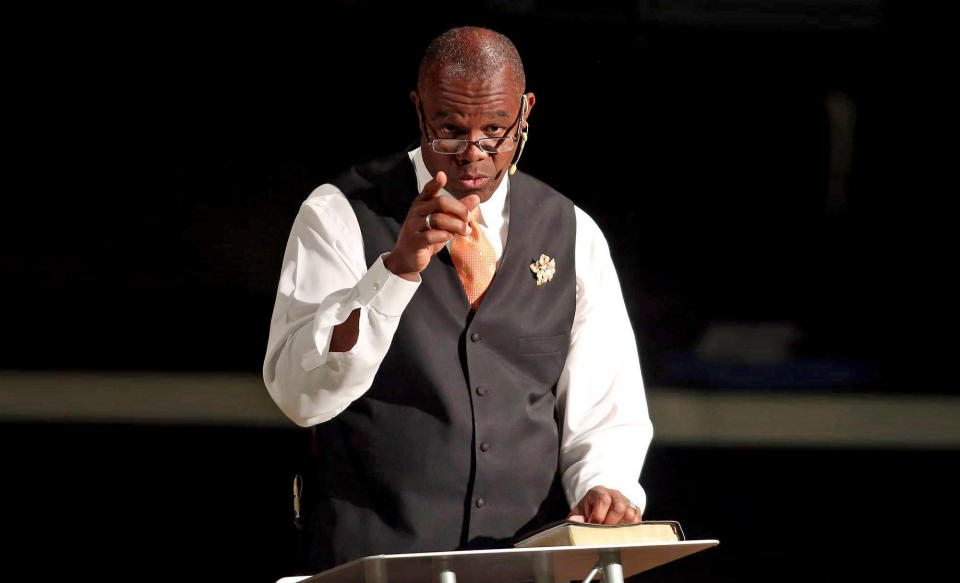

Some clap along. Then the music fades, and cedes the stage. A little before 8:30, applause begins to ripple. A pastor marches purposefully toward a lectern. He kisses his wife, and turns toward the crowd.

“Great morning, church!” he booms. “What's happenaaan!? We serve a great God, amen?”

And for the rest of the morning, his enthusiasm fills every last crevice of this balconied auditorium. A microphone and speakers help. His bright orange tie shrieks off an all-black suit. He teaches three services, to around 1,000 believers in total, following prepared notes each time but improvising with aplomb. He commands attention. And not just because his name is Randall Cunningham.

Yes, that Randall Cunningham. You know him as one of the most electric NFL quarterbacks ever. As a first-of-his-kind dual-threat star who captivated the league in the ’80s and ’90s. As a willing and able entertainer — a 20th-century precursor to Michael Vick and Lamar Jackson.

Here, he’s “Pastor Randall.” As he wades through a buzzing Remnant lobby, his nearly bald head poking up above the crowd, churchgoers greet his every step. He doles out handshakes and hugs. They don’t ask about football. They don’t flock to him because of three-decades-old exploits. Several months later, he’ll accept a role with the Las Vegas Raiders. But it won’t have anything to do with the sport he once infused with joy.

He’s Pastor Randall, and on this Sunday, the NFL’s conference championship games won’t wait for him. As kickoff nears, he says he won’t watch anyway.

“Philadelphia Eagles didn't make it, so there are no football games out there today,” he says with comedic charm.

Instead, he has a story to tell.

Today’s service, he explains, is entitled “The Parable of the Rich Fool.”

Life in the fast lane

To understand Randall Cunningham’s reinvention, to understand why an A-list NFL celebrity parlayed a near-Hall of Fame career into evangelical pastorship, one must first return to a time when not even Randall understood himself.

That’s when he was hurdling tacklers and rocket-launching deep balls. Slashing through defenses and slithering out of sacks. Life moved fast for young Randall, from a working-class family in Santa Barbara, California, to UNLV to Philly. And to an NFL world where, in his words, “anything goes. You date who you wanna date. You spend how much you wanna spend. You drive what you wanna drive. You live where you wanna live.” And Randall did date. He did spend, almost immediately after signing his rookie contract with the Eagles. He rolled up to training camp in a Porsche 944 before he’d thrown an NFL pass.

The more he saw the field, the faster life moved. His hype train accelerated. And Randall, without hesitation, jumped along for the ride. In fact, he was the conductor. He bathed in the attention. He gravitated toward glamor. He graced commercials and late-night TV shows. His irresistible smile gleamed off billboards. He once left a preseason game at halftime to attend Whitney Houston’s birthday party. Houston, MC Hammer, Evander Holyfield and Donald Trump were among 1,000 invited guests at his wedding, which reportedly cost $1 million.

“I admit that when I first entered the league I didn't fully understand the enormity of the situation,” Cunningham wrote in a 2013 book. “It's easy to stay self-focused, doing the things that make you feel good or make you more money or make you more popular. … I was more about me than anyone else.”

When he arrived in Philly, Reggie White ran the locker room. And White tried to reel in Cunningham. White was an ordained Baptist minister. He organized weekly Bible studies. He invited, then pressured, Cunningham to join.

Randall, on the other hand, grew up attending church on Sundays, but had no relationship with God. He called himself a Christian, but didn’t walk as one. He didn’t read the Bible often. When he did, he didn’t understand what it meant.

So when White approached, Cunningham resisted.

“Because I had my own life,” he says. “And I was trying to figure out me.”

Randall Cunningham finds God

It was in 1987, his third year in the league, when Cunningham began, slowly, to reinvent himself. He mingled with celebs and embraced self-promotion. But he also began to read scripture regularly. He remembers a golf outing with a friend in Vegas. The friend suggested he commit to Christianity. That day, Cunningham says, “I asked Christ into my life.”

Before long, fellow Eagle Cedrick Brown was leading a dozen teammates and friends in weekly Bible studies at Cunningham’s home. Cunningham also became a regular at St. John Baptist, a church in Camden, New Jersey, which “gave me a foundation, gave me order in my life,” he says. He’d sometimes sneak into Sunday services during the season when the Eagles played on Monday night. On the side, he dabbled in gospel music. Gradually, he matured.

It was as he cleaned up his life, though, that football setbacks muddied it. A torn knee ligament ended his 1991 season after four passes. A fractured fibula ended his 1993 campaign after four games. When it broke, he briefly pondered retirement. While injured, he’d watch games from the tunnel, crutches digging into his armpits or resting against his leg.

“During those days,” he wrote in 2013, “it felt as though no one cared about Randall Cunningham.”

And it was this “wilderness time,” as he called it, that helped change his life.

“It caused me to become a better person and teammate,” he wrote. “I realized that it wasn't all about me, or what I thought or wanted.”

That perspective informed the rest of his career. Across 10 years and four coaching regimes in Philly, he accumulated an endless highlight reel but only one playoff win. In 1995, the city soured on him. He got benched. As a breakup neared, a few fans hung a homemade banner from the facing of Veterans Stadium’s upper deck: “Randall: Don’t let the door hit you in the ass.”

The end in Philly left him disillusioned, so much so that he not only split with the Eagles, but with football itself. The NFL didn’t want Randall, and he didn’t want the league. Prior to the ’96 season he announced his retirement. He settled in Vegas. He started a tile company. He worked long days, sometimes until 10 or 11 at night, cutting marble and granite and installing custom countertops.

“I hated football,” he’d later write. “I was done. I never wanted to play football again.”

Becoming Pastor Randall

Back at Remnant, a little after 10 a.m., Pastor Randall is preaching about the “Rich Fool.” He interweaves scripture with personal anecdotes. He’s reading from the Gospel of Luke, chapter 12, reciting a verse about greed and overindulgence. About a man who has surplus crops and goods, and plans to keep them for himself – at which point God intervenes. And that’s when Pastor Randall breaks from the script, removes his eyeglasses and peers out into the crowd.

“I gotta testify,” he says.

He tells them about his retirement. “I was at this place – I was sick and tired of people criticizing me,” he says. He wanted to escape with his riches. “Multimillionaire, thinking that I didn't need anything from anyone. And I figured, you know what? My wife and I are gonna ride off in the sunset. I've had a successful career. We're just gonna go to Hawaii, raise our little boy, we're not gonna worry about anybody else.

“I had been beat down by the public so long that I felt there was a moment I could be selfish.

“And then I came to my senses. And I thought to myself, ‘You know what? It's not about me. It's not about what I have. It's not about what I'm going to get.’”

The moral of the scripture, he says, “equates to blessing other people.” That’s one thing he set out to do later in life. In 1997, he returned to the NFL a changed man. He not only participated in Bible studies in Minnesota, where he performed at an MVP level in the 1998 season, but arrived early to set up chairs. He attended chapel services. He befriended Vikings team chaplain Keith Johnson. “I was really underneath his wing, and learning Hebrew, and Greek, and memorization, and fasting, and prayer,” Cunningham says. “And learning how to teach, and different things like that. We went in the community and evangelized. And he really poured into my life.”

Cunningham’s career concluded with one-year stints in Dallas and Baltimore, where he’d meet every Monday with teammates to study “The Man God Uses.” During offseasons, he and his wife, Felicity, hosted Bible studies at their home in Nevada. When he retired for good in 2002, his faith-based ventures grew. First came recording and dance studios. Then the larger facility at 325 East Windmill Lane. Bible studies soon doubled as communal meals, and multiplied in size. Randall organized “men’s accountability” meetings. His network expanded, and ultimately became Remnant Ministries. In 2004, Randall became Pastor Randall, and Remnant became a full-fledged church.

Ever since, it has been a cornerstone of Cunningham’s life. As the community swelled, its ethos remained intact. The facility, which features classrooms and a basketball court, hosts a variety of events six days a week. On Sundays, greeters shake hands and brighten mornings at the door. Bubbly conversation fills the lobby. Longtime members welcome strangers with “God bless yous,” and one another with hugs.

After services conclude, a line of diverse attendees awaits Randall. He makes time for each of them. Even for the non-believers who just want to meet a former MVP.

A man of many hats

In pre-pandemic times, especially during summers, the Philadelphians would show up. The Kelly Green jerseys make them easily identifiable. They hop out of Ubers, and slink around timidly outside, in search of their childhood favorite. Occasionally, a Remnant staffer would recognize their intentions, wave them inside and introduce them to Cunningham. No matter where he goes in life, his NFL stardom will stay attached. The football world will hold him in high regard.

But Randall, upon retiring, drifted away from football. “It consumed a lot of my life. I needed a shift,” he explains now. He maintained some NFL friendships, but mainly through religion. Rod Woodson, a Vegas resident, attends his services regularly. Ray Lewis spoke at one of his men’s accountability classes earlier this year.

He coached for a few years at a local high school, but has since moved on to track and field. His children are high-jumpers. Vashti, the second-oldest, could be an Olympic medal favorite.

A day after teaching “The Parable of the Rich Fool” at Remnant, Randall pulls up to the training facility he built across the street. He pops out of his silver Benz. He maneuvers a toothpick side-to-side in his mouth. And for two hours, he challenges Vashti, pushing her through a series of jumps and a strength circuit. When they disagree on the finer points of technique, occasionally she pushes back with a sharp “DAD!” and a scowl. But when they finish, they flip from coach and athlete back to father and daughter.

Randall wears several figurative hats, with “dad,” “pastor” and “coach” chief among them. His schedule is packed. Prayer, worship, study and parenting fill most days. When stress spikes and the word of God doesn’t relieve it, he’ll sometimes escape to an empty movie theater. At 11 a.m., it’s his “peaceful place.” And “I just fall asleep in the movies,” he says. “I pay to go take a nap.”

Yet earlier this year, he added another responsibility. Raiders head coach Jon Gruden called him up in search of a team chaplain. After extensive prayer, and knowing how valuable chaplains had been during his own career, Cunningham accepted.

Three months into the role, COVID-19 has limited it. Cunningham can’t enter the Raiders’ facility, so he meets with players via Zoom on Saturday nights. Throughout the week, though, he fields phone calls. He chats with Gruden. He checks in on Derek Carr, Marcus Mariota, Nelson Agholor.

His job, he says, is similar to his role as pastor. It specifically pertains to Christianity. It’s to “teach them the Bible. I give them inspiring messages about characters in the Bible,” he explains. But he’s also a resource, a pillar in the team’s support system, a dispenser of encouragement. “And once I encounter a player, they go on my prayer list,” Cunningham says. Ditto for coaches, other staffers, and employees’ family members. “I pray for them daily,” Cunningham says.

He is not, he assures, a football coach of any kind. His expertise and passion now lie elsewhere. Even back in January, during a sermon at Remnant, his sole mention of Vegas’ incoming NFL team was telling.

“I mean, the Raiders are coming to town, that's gonna be cool,” he told the congregation.

“But, but, but that's not a suffice for what God wants us to do. If we go to the Raiders game – after church,” he clarifies, then pauses for laughter – “God might just want us to minister on the way over there.”

Stats don’t always matter

Cunningham has, more recently, been following football as time permits. And he has recognized what many analysts have: that his 25-year-old game would suit the modern NFL quite well. He sees how the sport has evolved. “My friend, I'd love to be playing now,” he says.

He also thinks he played a role in the sport’s evolution. He brings this up when asked about the Hall of Fame. “The way you're supposed to get in the Hall of Fame, from what we all understand as players, is your impact on the game,” he says. “If you have impacted your position, then you should be able to get into the Hall of Fame. My statistics, I might've been [21] yards short of 30,000 [passing yards], I might be [72] yards short of 5,000 [rushing yards]. But nowadays, when you look at the game … last year, the Rookie of the Year was [Kyler] Murray from the Arizona Cardinals. The MVP of the league was my brother over in Baltimore, Lamar Jackson. And then the MVP of the Super Bowl was the young buck, [Patrick] Mahomes. So we go from not having players play the position of quarterback, to all of a sudden …

“Doug [Williams], myself and Warren [Moon] were involved in that,” Cunningham concludes. “These guys, they did, they transformed the position. And I think all three of us should be in there.”

When pressed on whether he cares about his exclusion, he brushes it off. “I'm not gonna politic to get in the Hall of Fame,” he says.

He has moved past accolades and trophies. Back at Remnant, he explains why. "I can say, ‘You know what, I was the MVP, I was the MVP, I was the MVP,’” he says. “I’ve got an honorary doctorate. I can say, ‘I graduated from UNLV.’ I've got Pro Bowls.” Then he cuts off the list to flip to a more serious tone.

“Let me tell you, none of that justifies who we are. That doesn't mean anything.

“How are we gon' puff out our chest to God?"

The remark draws laughter and introspective thought. Even at 57, Randall Cunningham still regularly inspires both.

“Preach, pastor!” screeches a woman a few rows from the stage.

“Amen,” murmur a dozen others. “Amen.”

More from Yahoo Sports: