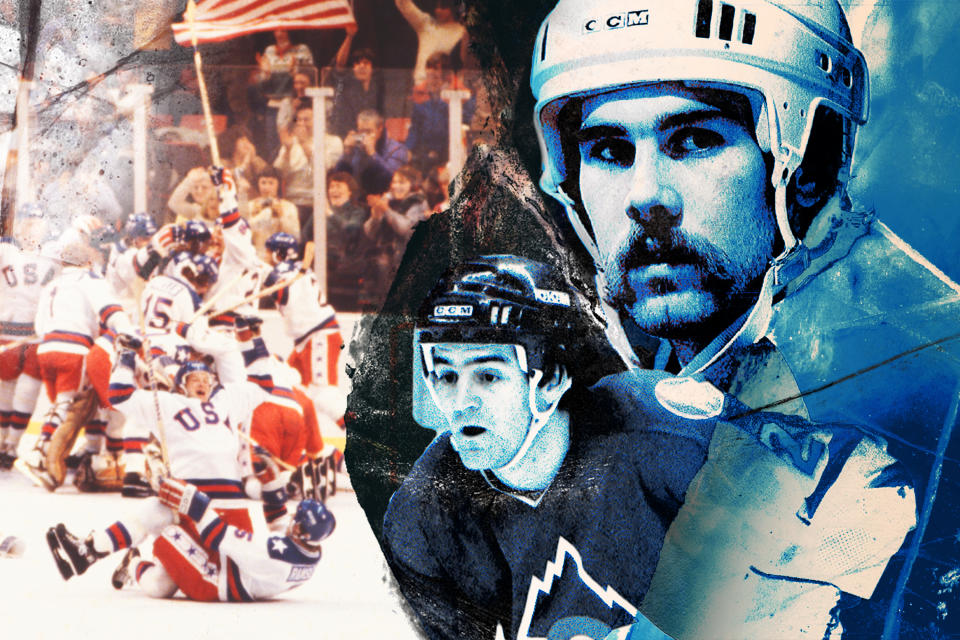

The men who missed the Miracle on Ice

Herb Brooks was pacing. Slowly, softly, with care but unease. On a frigid Minneapolis morning, he was alone in a hotel banquet hall. Round tables and chairs lined the room. Caterers prepared a feast. A celebration neared. And yet Brooks wore distress on his taut Minnesotan face.

Because before long, the empty hall would fill. U.S. hockey officials would file in. Local business leaders would follow. And Brooks, the head coach, would present to them the 20 amateurs he’d be taking to Lake Placid for the 1980 Olympics. The 20 who for months had skated together until their quads shook and their glutes burned. Who’d traveled the world and bled together. Who’d downed beers and suffered together, all in their quest to make the team.

Soon, they’d lock up their apartments, pile into cars and head to the banquet hall for their sendoff. Then they’d board a plane to begin final preparations for the Olympics. They buzzed with excitement.

The problem for Brooks: There weren’t 20 of them. Hours before the announcement, there were 22.

Back at the apartment Mike Eruzione shared with Ralph Cox, the phone rang.

Cox and Eruzione were both Massachusetts guys. So were Jack O’Callahan, Jack Hughes and Dave Silk. The five had gathered together, as they often did during those unforgettable months, to carpool to the luncheon.

Eruzione picked up the phone. He handed it to Cox. “It’s for you,” he said. And the Boston boys went silent.

Cox pressed the phone to his ear. “Yeah. Yeah. Uh huh,” he muttered. “Yeah. Yeah. OK.”

Soon after he hung up, the phone rang again. This time, Eruzione handed it to Hughes.

Pretty soon, Hughes and Cox were on their way to the hotel, where Brooks paced. When Cox entered the room, Brooks held up a finger. “Just give me a minute,” was Cox’s interpretation. “And I could just see how upset he was.”

Then player and coach sat down. Words almost seemed caught in Brooks’ throat. Forty years later, memories of the ones that actually came out are hazy. But they were heartfelt. They took Brooks back to his own experience as a player, as the last cut from the gold medal-winning 1960 Olympic team. So they brought tears to his eyes.

“I can’t take you with us,” coach said, and already sunken hearts sunk even further.

So 22 became 21. Minutes later, it was Hughes’ turn, and 21 became 20.

Gut-wrenching goodbyes were said. The 20 then embarked on a journey that would make them American heroes, that would culminate in the Miracle on Ice, the greatest upset in sports history, which took place 40 years ago Saturday.

Hughes and Cox, meanwhile, taxied to the airport. They boarded a small plane destined for Boston. It glided up into the clouds. And you, in all likelihood, never heard from them again.

Two kids, one dashed dream, two paths

Ralph Cox was born in Braintree, and Jack Hughes in Somerville, five months and 15 miles apart. They crossed paths frequently as children in suburban Boston, dueling in youth hockey leagues. And they shared a dream. For Hughes, the seed was planted at a family friend’s house. Stored away in a closet, and occasionally pulled out for show-and-tell, was a blue USA Hockey jersey. “Wow,” Hughes thought at the sight of it. “That opened my eyes, when I was a kid, to playing hockey for my country, and what it could mean,” he says now.

Cox, too, envisioned the red, white and blue. “Kids dream about growing up and playing pro hockey,” he says. “I dreamed about growing up and representing the U.S. It had more meaning in my family.”

Simultaneously but separately, they rose through the ranks. Cox still remembers the pride he felt whenever he tugged that Archbishop Williams High School jersey down over his pads. He then went off to the University of New Hampshire, while Hughes enrolled at Harvard. An attacker and defenseman, respectively, they ascended toward the top of the nation’s amateur player pool. Cox says he had offers to leave UNH early and turn pro. The Olympics, however, were a year away. Money could wait.

In 1979, their parallel paths became one. They and 24 others became an extended family, enduring travel and grueling practices arm in arm. Both survived the Olympic training camp cut from 26 down to 22. As February 1980 neared, both felt they deserved to make the 20.

Brooks, however, felt otherwise.

Both were invited to accompany the team to Lake Placid as glorified cheerleaders. Both declined. And so their paths diverged in agony. Cox watched the Olympic opener with his father. “That was tough,” he admits.

They jetted off to NHL farm teams, Cox to Tulsa, Oklahoma, Hughes to Fort Worth, Texas. Neither watched the Soviet game. Forty years later, neither has ever watched it in full. Cox did catch the gold-medal clincher, a 4-2 win over Finland. He calls it “amazing” and “awesome.”

“After it was over,” he says, “I was like, ‘Oh, sh—, man, I wish I was there.’ ”

They were thrilled for teammates, but Hughes was disappointed and angry; Cox was devastated, empty, “down in the dumps.” He returned home for the summer. One afternoon, he hopped in his 1967 Ford Mustang and cruised to a nearby estuary to fish. Perhaps it would ease his frustration, grant him some peace of mind.

Instead, on the banks of the river, he slipped. Lost his balance. In an attempt to steady himself, he jammed his fishing rod into a rock. The rod broke. He hurled it into the water. Kicked his lure box in with it. And stormed off.

He trudged back to the Mustang. Reached into the backseat. Grabbed his hockey sticks and took one to a small bridge. He squared up to the railing, wound up and – THWACK! – it splintered in two.

Then he reached for the second and – THWACK! – again.

Then he drove home. Pulled into the driveway, and moped into the house. His frustration had festered, simmered, built up over months. Finally, on Cape Cod in June, he’d snapped.

But here, in the nuances of their emotions, is where their stories differ. Cox was “devastated,” even “embarrassed” after being cut, but never angry at others. Hughes, though never embarrassed, absolutely was bitter. Whereas Cox loved and respected Brooks, Hughes had clashed with the uncompromising coach.

For the most part, he stays polite when the subject of their relationship arises. “We did not see things eye to eye — and, um, I’ll just leave it like that,” he says. But he hints at acrimony. Between his departure from that hotel room and Brooks’ 2003 death, Hughes saw his former coach twice. First, when he played against the Brooks-coached New York Rangers, the two didn’t acknowledge each other. The second time was between periods at a college hockey game years later. Hughes spotted Brooks in the concourse, 30 feet away. He says their eyes locked. And, he says matter-of-factly: “I really didn’t have any desire to go over and say hello.”

The movie’s distortion

Fifty-seven minutes into the 2004 movie “Miracle,” Disney’s classic retelling of the 1980 team’s tale, assistant coach Craig Patrick swings open a door and strides into a banter-filled locker room. He beelines toward Cox, and without any pleasantries …

“Coxey,” he says, “Herb wants to see ya.”

Cox freezes. The banter dies down. Dramatic music replaces it.

Brooks is sitting in his office. He hears a knock. “Come in,” he says through tight lips, and Cox does. He takes a seat. “We gotta be down to 20, and right now we’re at 21,” Brooks tells him. And without actually saying the words, he tells Cox he’s No. 21.

Millions of Americans have seen the movie in the 16 years since its release. Millions have felt that scene. Many have been entranced. They’ve repeated lines and been inspired by characters. Two, however, had a different reaction. Jack Hughes’ kids watched it. They came to him and said: “Dad, I thought you were the last guy cut?”

“I was,” he told them, but he didn’t have a satisfactory explanation for why Disney said otherwise.

He’d approached Jack O’Callahan about it. O’Callahan said – and today confirms – that he wrote to the film’s producer to say the portrayal wasn’t accurate. The producer ignored the correction, and with that, two “last cuts” became one, Hughes’ story forgotten and Cox’s memorialized. “The media and the movie and everything have made it all about Ralph,” Mike Eruzione says. “And that really wasn’t the case.”

Yet to the public, it has been. Cox is the one who gets the occasional interview request. Hughes hadn’t had one in years. When I began reporting this story, Cox was the man I turned to. In our first two interviews, he didn’t mention Hughes. He referred to himself as “the last man standing.”

The contorted narrative bugged Hughes for a while, but not because he cared about Hollywood acclaim. Rather, because he suspected he knew a reason for it. Brooks, before his death, served as a consultant on the film. The same Brooks who wept during his extended meeting with Cox at that Minneapolis hotel, and who saved no tears for Hughes. The same Brooks who later worked alongside Cox in the Pittsburgh Penguins’ scouting department, and who never spoke with Hughes again.

“I think Herb Brooks had some influence,” Hughes says. “Other than that, I don’t have anything else to offer. It’s a Hollywood film. A lot of it’s true. Some of it’s not.”

“But believe me, I do not lose sleep over it,” he assures. In fact, he has a “Miracle” movie poster framed by hockey-stick segments hanging from a wall in his home. It’s signed by his 1980 teammates, many of whom he hasn’t seen in decades. Some of them, in interviews, assumed Hughes would not want to talk for this story. But he did, and he has moved on — from the movie, from the disappointment of 40 years ago, from the anger.

Cox has as well. “It was just a devastating moment as an athlete. And it really hurt,” he says. “But I love those guys. And I love the team. And I liked Herb Brooks. And I’ve been asked so many times, ‘If you had to go through all that again, would you do it?’

“And I say: ‘Honestly, tomorrow. Even though I have to face all that pain again, I’d do it all over again.’ ”

The lesson learned

When he returned home after the stick-snapping outburst, Cox’s dad invited him out back. They sat at a picnic table by the water under a setting summer sun. Dad talked about fighting in World War II, and about perspective. He talked about opportunity and fortune. He acknowledged how difficult Ralph’s Olympic disappointment had been to bear.

“But,” father told 23-year-old son, “you’re just at the beginning of your life.”

The next morning, Cox’s phone rang. It was a hockey agent. SaiPa, a team in the southeastern Finnish town of Lappeenranta, was in the market for an attacker. Coxey fit the profile. The agent wanted to know: Was he interested?

He was, and in a span of roughly 16 hours, his world had flipped back upright. He went to Finland, had a “remarkable” experience, “and I realized that I actually loved playing hockey. Breaking the sticks over the bridge, that was such a momentary thing. Oh, just so frustrated. But then you gotta move on, you gotta go forward.”

Hughes, completely unaware of Cox’s fishing story or his turning point, has the perfect metaphor: “Sometimes, you need to slip off the rocks and jump back on if you want to get across the river.”

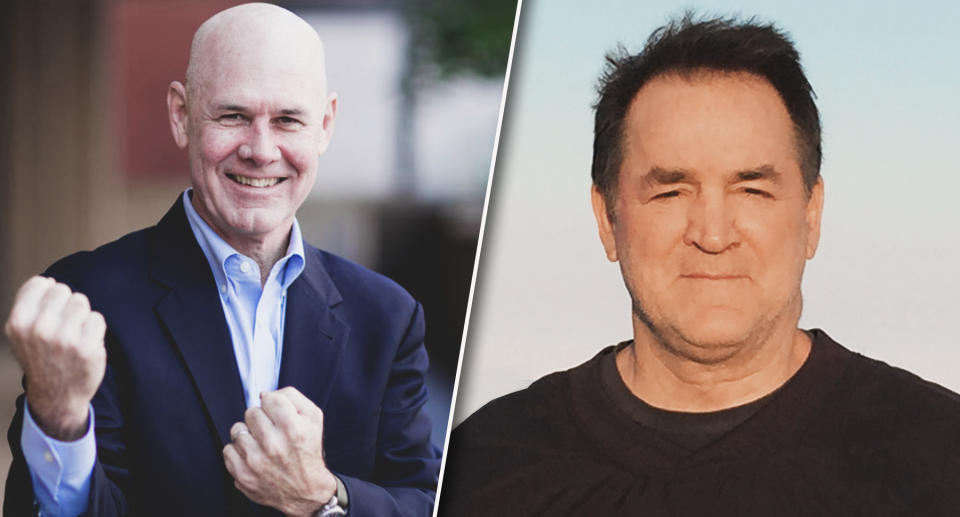

They both did, and have enjoyed successful decades-long careers, Hughes in investment advising, Cox in real estate. They both married and have multiple kids. They both say they learned positive lessons from 1980. And they both lead happy New England lives today.

Hughes, although he started a business with O’Callahan and worked with him for 25 years, has chosen to remain relatively distant from most 1980 teammates. Of declining invites to various team functions over the years, he says: “I felt it was their celebration.” Cox, on the other hand, accepts invites and still connects with teammates regularly, at both official and unofficial get-togethers. He participates in their fantasy camps in Lake Placid. He was invited to this weekend’s 40-year reunion in Las Vegas. He raves about the team’s character and camaraderie. When asked whether he ever thinks to himself, Damn, I wish I would’ve been a part of that, he responds: “You know, I was a part of it. That’s the thing.”

And in a way, his story is just as powerful as that of the 20 heroes you know. Disney preserved its essence, even if not the details. The result is calls, emails, snail mail from all over. From people who are fighting deadly diseases or simply fighting a middle-school coach who doesn’t value their daughter. When Cox can, he’ll call back, or even pay the afflicted fan a visit.

A few years ago, he received a call from a man in a Midwestern suburb. A neighbor’s son, whom we’ll call Tommy, had just been cut from his high school hockey team. Tommy could barely get out of bed. His parents were worried. He was devastated, embarrassed, just like Coxey once was. And Coxey happened to be his favorite character in “Miracle.”

So Coxey asked for Tommy’s number, and gave him a ring. “And we had a wonderful conversation. I mean, it was powerful, both ways,” Cox says. He gave Tommy his spiel, about his own life experiences, and about optimism, positivity, and so much more. About turning a gut-wrenching moment into a fulfilling life.

At around 10:30 that night, Tommy called back.

“Hey Mr. Cox,” Ralph remembers him saying. “I want to let you know, I took what you said seriously. And I realized there was a tryout for the local junior team. And I went down. And the coach was so thrilled to have me there. And he already told me I’m on the team.”

More from Yahoo Sports: