What fuels the fire inside Lamar Jackson? Just tell him he 'ain't a quarterback'

Anytime Lamar Jackson wasn’t sharp enough during passing drills last offseason, his longtime quarterbacks coach knew just how to light a fire under him.

Joshua Harris would allude to the lingering doubts facing Jackson about his ability to throw at an NFL level.

“This is why they say you ain’t a quarterback!” Harris would bark if Jackson misfired on an easy pass. It was a reference to last year’s NFL draft when some teams didn’t think Jackson could make the necessary throws to run a pro-style offense and asked the former Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback to work out at receiver or running back instead.

Jackson led the Baltimore Ravens to a 6-1 record as a starting quarterback last season, but the rookie’s harshest critics harped on his low completion percentage (58 percent), penchant for fumbling (12) and overreliance on his running ability (147 rushes vs. 170 passes). As a result, Harris was quick to roast Jackson during drills if he fled the pocket at the first hint of pressure, quipping, “No wonder everyone thinks you’re just a runner!”

“I’ve never seen a player who responds so well to criticism,” Harris told Yahoo Sports. “If I mention something someone said about him to try to get him going, the next throw he makes is always perfect. I’ve realized that’s something that he thrives on.”

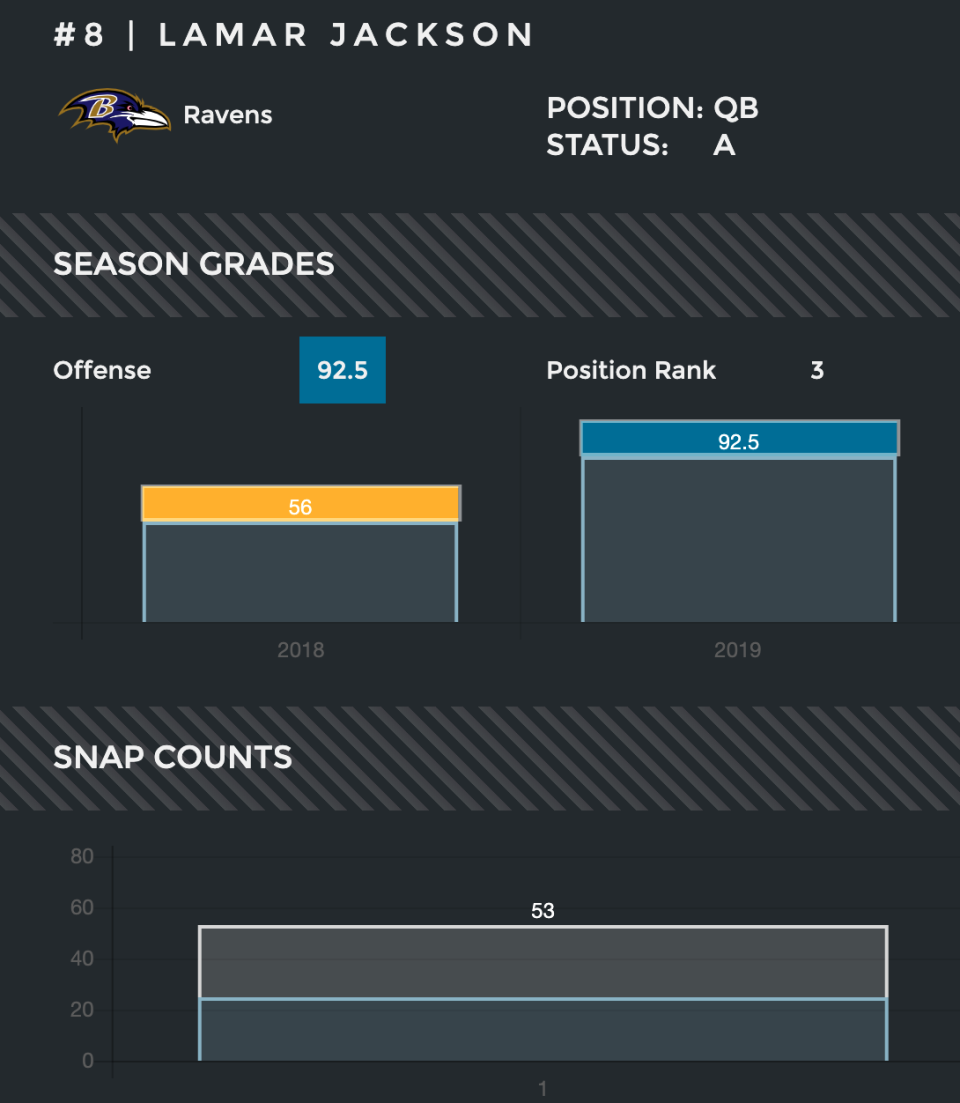

Fueled by the desperate desire to prove the Ravens right for believing in him and to make his many critics eat their words, Jackson enjoyed some long-awaited vindication Sunday afternoon. The second-year quarterback went 17-of-20 for 324 yards and five touchdowns in a season-opening 59-10 thrashing of the Miami Dolphins.

It would be foolish to overstate the importance of one game against an overmatched opponent, but it’s certainly noteworthy that Jackson destroyed Miami with his arm instead of his legs. He rushed just three times for 6 yards, a clear message that he’s more than just a dazzling athlete.

When asked if his perfect quarterback rating and franchise-record completion percentage would finally put an end to the talk that he’s not an NFL-caliber passer, Jackson flashed a wry grin and pounced on the chance to clap back at the naysayers.

“Probably not,” Jackson told reporters in Miami, “but not bad for a running back.”

Ask people close to Jackson to explain his apparent offseason improvement as a passer, and they’ll typically cite two factors. They point to the Ravens installing a new passing attack tailored to Jackson’s skills and Harris finally having time to refine the quarterback’s unconventional throwing mechanics.

Having jettisoned Joe Flacco over the offseason and thrown all their chips in on Jackson, the Ravens tasked offensive coordinator Greg Roman with overhauling the playbook in their quarterback’s image. Roman was an ideal choice given his experience exploiting the strengths of another exceptionally mobile quarterback, former San Francisco 49ers starter Colin Kaepernick.

In addition to learning the new playbook, Jackson also worked with Harris all offseason to fix the mechanical flaws that limited his effectiveness passing the ball as a rookie. They spent a few mornings and evenings a week doing throwing drills on the South Florida field where Jackson once played youth football, often flying in Ravens or ex-Louisville receivers for additional help.

Harris’ goal was to deliver the Ravens a true dual-threat quarterback by the time training camp began rather than the one-dimensional running specialist of a year ago.

“What he can be is something the league hasn’t seen,” Harris said. “He can give you what any pocket passer can give you but then when there’s nothing there, he can take off and make an explosive play. That’s his ultimate ceiling, but we are still working on creating the discipline that it takes to do that.”

Over the next few months, it should become clearer whether Jackson’s near-flawless passing performance against Miami will be remembered as a bizarre anomaly or the start of a trend. For now, it’s another step in his obstacle-laden journey from unpolished recruit, to polarizing draft prospect, to budding NFL success story.

The rise of Lamar Jackson

Jackson’s football odyssey began in Pompano Beach, Florida, 14 years ago with a straightforward challenge from his first youth football coach.

Van Warren told the 8-year-old that he had to demonstrate he could throw a football at least 20 yards if he wanted to compete for the starting quarterback job. If Jackson fell short, he would have to play another position.

“I walked 20 yards, and he threw a dime,” Warren said. “I was like, ‘Alright, let’s go to work.’”

— Lamar Jackson (@Lj_era8) December 18, 2018

Tales of Jackson’s video game-esque youth football exploits generated plenty of buzz when he transferred to Boynton Beach High School late in his sophomore year, but head coach Rick Swain insisted the newcomer would have to earn the team’s starting quarterback job. The competition ended 30 minutes into Jackson’s first practice after he displayed a combination of speed, elusiveness and arm strength Swain had never witnessed from a high school prospect before.

Jackson’s dual-threat ability prompted Swain to switch from a traditional spread offense to a no-huddle pistol scheme. In two years at a historically downtrodden Boynton Beach program, Jackson led the team to a 20-4 record and produced more than 5,000 yards of offense, 3,033 through the air and 2,440 on the ground.

It’s difficult to imagine any college coach not pursuing Jackson after watching his jaw-dropping high school highlight reel, but in reality the future Heisman Trophy winner was not considered a can’t-miss recruit. Rivals rated Jackson a four-star prospect and the 17th-ranked dual-threat quarterback in the 2015 class. Scout and ESPN awarded him only three stars.

One concern that scouting services had about Jackson was that his completion percentage was unusually low for a quarterback prospect with high-major arm talent. Jackson also played in a rudimentary offense that relied on his ability to freelance and seldom required him to read defenses and find open receivers from the pocket.

Among the first college recruiters to fly to Boynton Beach to assess Jackson in person was Louisville wide receivers coach Lamar Thomas, a former all-state high school receiver under Swain years earlier. Swain successfully piqued Thomas’ curiosity when he described Jackson as the best athlete he had ever coached, no doubt as much a friendly dig at Thomas as a compliment for Jackson.

“That really got my attention,” said Thomas, himself a former eight-year NFL veteran with the Miami Dolphins and Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

‘When I went to see him, he was a little raw, but he was a really good athlete. I saw him running, I saw him spinning, I saw him juking, I saw him throwing. I said, ‘Wow, this kid is legit.’ ”

Thomas had the inside track to land Jackson thanks to his relationship with Swain, but first he had to persuade Louisville head coach Bobby Petrino to approve a scholarship offer. Petrino was impressed with Jackson’s speed, strength and elusiveness but did not initially see an ACC-caliber quarterback.

To get Petrino to change his mind, Thomas altered Jackson’s highlight reel to eliminate his running plays and showcase only his arm. Watching Jackson effortlessly send deep balls 60 yards with a flick of the wrist, Petrino saw a different quarterback.

Once Petrino agreed to recruit Jackson to play quarterback, Louisville emerged as an instant contender to land him. Many other schools envisioned Jackson transitioning to another position in college, a deal breaker in the eyes of him and his mother, Felicia Jones.

“That was not something to even entertain,” Warren said. “If you weren’t talking quarterback, there was nothing to even talk about.”

Jackson’s four finalists were Louisville, Florida, Mississippi State and Nebraska, each of whom recruited him as a quarterback. Louisville emerged the winner by showing Jackson he’d have a realistic chance to compete for the starting job right away instead of sitting for at least a year or two behind a veteran.

Before Jackson committed, Jones told Petrino she needed him to promise he’d play her son exclusively at quarterback. Petrino kept his word with one exception, a practice early in the 2015 season when he was in desperate need of a dynamic punt returner and offered Jackson a crack at it.

Only minutes after practice ended, members of the Louisville staff received a phone call from Jackson’s mother. She reminded them of the promise Petrino had made in her living room and that was the end of the punt returning experiment.

“To this day, we still don’t know how she found out so fast,” Thomas said with a chuckle. “The kid caught the ball so effortlessly and everybody was like, ‘Hmmmmmm.’ But in the back of my mind, I knew we had made that promise and we had to stick to it.”

Tantalizing as it was to unleash Jackson all over the field, Louisville clearly made the right call building its offense around the future Heisman Trophy winner’s unique talents at quarterback. Jackson emerged as one of the nation’s elite dual-threat quarterbacks, throwing for over 9,000 yards and 69 touchdowns during his decorated three-year college career and adding more than 4,000 yards and 50 touchdowns on the ground.

The man behind Jackson’s star turn

It’s no accident that Jackson’s star turn at Louisville coincided with his decision to entrust his throwing mechanics to an instructor with an unusual background for his gig.

Harris played defensive end at Tennessee State in the early 2000s before leaving football behind and earning his law degree. He only began researching how to instruct quarterbacks when he started coaching high school football in Florida and his son started to take an interest in playing the position.

A maniacal researcher with a thirst for knowledge, Harris poured himself into his new passion, devouring books on the fundamentals of throwing a football, volunteering at clinics run by prominent quarterback coaches and studying film of the likes of Tom Brady and Drew Brees. Within a few years, Harris understood the nuances of the quarterback position better than most of the men who have played it.

It was through Warren that Harris first met Jackson before the quarterback’s sophomore season at Louisville. Harris worked with Jackson at a handful of Warren’s Sunday passing clinics in Pompano Beach, swiftly establishing a strong rapport with the Louisville star and his mother.

By that time, Warren thought he had taught Jackson all he could about the quarterback position. He urged Jackson to begin working with Harris on his mechanics.

“I thought Coach Josh would be able to take Lamar to the next level and I was right,” Warren said. “Like I tell anyone, it was Coach Josh and his planning taking Lamar to where he is right now.”

For two years, Harris followed Louisville’s plan for Jackson, helping him learn the scheme that Petrino built for him and putting him through drills designed to help him thrive. Only when it was time to begin preparing for the 2018 NFL draft did Harris begin addressing some of the many concerns scouts had raised about Jackson’s potential transition to the pro game.

Aware that NFL teams were wary that so much of Jackson’s college success had come in the shotgun formation, Harris advised his pupil to take every snap under center during his pro day. Harris also emphasized passing concepts during that nationally televised workout in an effort to address concerns about Jackson’s ability to read a defense and find an open receiver.

Jackson did not run the 40-yard dash at the scouting combine because Harris felt a speedy time might fuel the calls to move him to receiver. Never did Jackson work out for any NFL team at running back or receiver because he wanted to make it clear that quarterback is his position.

“He has been a quarterback his whole life,” Harris said. “He never told me the talk of him playing other positions hurt, but I think it was like, ‘Why are they saying that? I threw for 9,000 yards in college!’ He felt like he had already shown people he was a quarterback by then.”

If last offseason was all about draft preparation, then this one offered more time for Harris to refine Jackson’s mechanics.

One point of emphasis from Harris was helping Jackson find a consistent rhythm with his 3- and 5-step drops to help him better time his passes to receivers. When watching film from last season, Harris felt Jackson often allowed the pass rush to dictate the pace of his drops.

Another point Harris stressed was Jackson being more disciplined aligning his feet, hips and elbow to his eyes. Jackson’s failure to adhere to that basic concept as a rookie contributed to his accuracy issues, especially on passes outside the numbers.

The drill Jackson hated most was Harris’ unusual method of making him comfortable staying in a collapsing pocket and surveying his downfield options. Harris would simulate conflict in the pocket by swinging a broom at Jackson, forcing him to learn to move his feet and reset them before throwing the ball.

“I’ll swing it, swing it, swing it and then I’ll say, ‘Throw,’ and he has to make an accurate pass,” Harris said. “If he doesn’t, he knows it’s 10 pushups.”

The fruits of Jackson’s offseason work were on display Sunday afternoon when he shredded his hometown Miami Dolphins without hardly resorting to scrambling. The quarterback whom so many wanted to transform into something else showed that his arm is just as dangerous as his feet.

It was a surprise for many around the NFL. It was vindication for Jackson and his inner circle.

“With all the scrutiny he faced preparing for the draft and during this past offseason, to have him have that good a day was a feel-good moment,” Harris said. “I’ve told him, ‘You’ve been proving people wrong your whole life. Let’s just continue to do that.’ ”

More from Yahoo Sports: