Summer of Dak Prescott featured dominoes, a tide of endorsements and reflecting on Romo

HAUGHTON, La. – On a muggy afternoon earlier this summer, the echo of dominoes crashing down on a metal table provide the soundtrack for a poolside gathering. Howls of laughter and volleys of trash talk alternate with the domino collisions, a decibel level reached only when old friends convene. Dak Prescott takes turns at the table with his brother, Tad, and his crew, the guys he played ball with in high school, grew up near in the trailer park and remains close with today.

On a rare summer day off in the wake of Prescott’s historic rookie season with the Dallas Cowboys, he’s at a poolside casino cabana beneath an Interstate 20 off-ramp on the outskirts of Shreveport adjusting to his new normal. Everything has changed as he emerged as the Cowboys’ starter and NFL Rookie of the Year, yet Prescott remains singularly focused on nothing changing.

A glimpse of Prescott’s future flashes behind him at the cabana, as ESPN provides breathless coverage of Derek Carr’s $125 million contract extension with the Oakland Raiders. Prescott’s past sits across from him, as his boys – Trent Jacobs, Cobi Griffin, Jordan Craft – treat each dominoes match like fourth-and-goal in the Super Bowl. The reality of his new life looms around him, as his confidant and marketing agent, Peter H. Miller, has his cell phone pressed to his ear to handle the logistics of the Dak Prescott football camp in his hometown, Haughton, the next day.

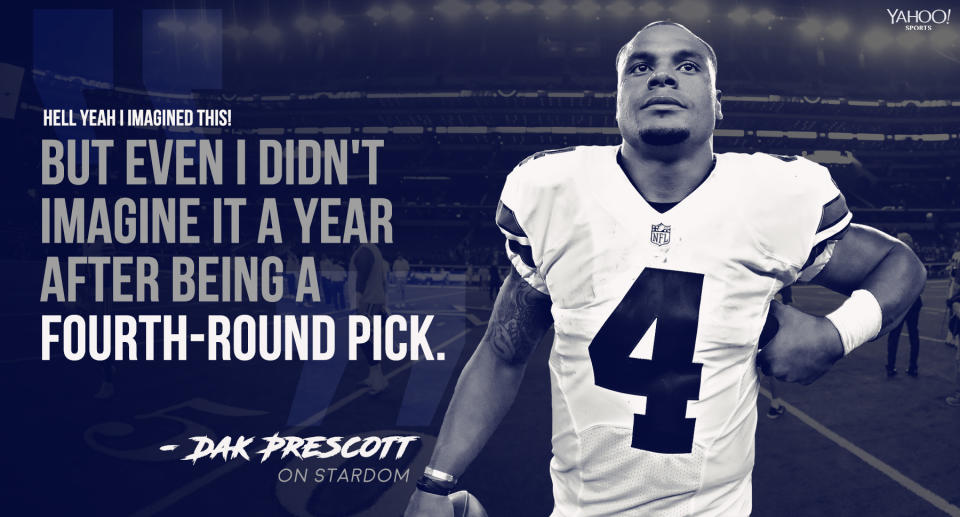

Few athletes in recent NFL history have altered their career arc as precipitously as Prescott in 2016. Just over a year ago, he arrived at Cowboys camp a fourth-round pick splitting third-team reps. He’d just stopped driving the Ford Focus he used during college at Mississippi State, the one he always left unlocked with the keys inside. Prior to last season, Prescott told his friends that he’d provide game tickets only to his father and brothers to save money. “People always say, ‘Can you imagine this?'” Prescott says. “Hell yeah, I imagined this! But even I didn’t imagine it a year after being a fourth-round pick.”

By now, the backstory has been told and re-told. Injuries to backup Kellen Moore and starter Tony Romo thrust Prescott into the starting job. He refused to yield it, orchestrating a franchise-best 11-game winning streak. Along the way, he broke the NFL rookie record for quarterback rating (104.9), registered a 23-to-4 touchdown-to-interception ratio and played so well that Romo eventually retired to the broadcast booth. Prescott handled everything with a grace best summed up by a viral video of him getting up off the bench to throw away a Gatorade cup that he’d errantly tossed at a trashcan. Even his misses were hits.

Superstardom, with all of its perks, temptations and complications, arrived for Prescott at Amazon Prime speed. A vote of NFL players this offseason, compiled by the NFL Network, ranked him the 14th best player in the league. He’s the face of the Cowboys’ future, especially with fellow second-year star Ezekiel Elliott suspended by the NFL for engaging in what the NFL called “physical violence” with a woman. (He’s appealing the suspension). And that means a trajectory for Prescott to potentially becoming a face of the NFL if postseason victories and Super Bowl appearances follow his star-kissed rookie season. After going 13-3 as a rookie and losing to the Green Bay Packers in the playoffs, those are the Cowboys’ next logical goals. “It was just Year 1,” Prescott says. “My whole life has been about getting better.”

About 15 miles from the poolside canopy, Prescott began his out-of-nowhere story. He grew up in a trailer park, raised primarily by a strong single mother whom he lost to cancer while in college at Mississippi State. He was overlooked by local power LSU in high school and saw seven quarterbacks drafted ahead of him after college. With a career narrative of being overlooked keeping him grounded, Prescott promises to remain rooted in the past. “Nothing,” he says, “changes now.”

****

How can nothing change when everything has? That’s the central tension of Prescott’s second NFL season. On the surface, everything is different. Prescott moved out of his three-bedroom condo, which he still rents for family and friends. He bought a $1 million home in a gated community, where he lives by himself.

Prescott will make $540,000 in NFL salary this year, and his slotted fourth-round contract of $2.7 million over four years makes him one of the biggest bargains in sports through the 2019 season. (And will allow the Cowboys to keep the robust supporting cast around him. That includes the league’s best offensive line providing Brink’s truck protection for Prescott). He’s leveraged his performance, storybook rise and relatable charisma to ink more than a half-dozen endorsement deals this offseason. Those included Pepsi, AT&T, Frito-Lay, Beats by Dre, Campbell’s Chunky Soup and 7-Eleven. Adidas, one of his few sponsors prior to his rookie year, ripped up his deal and gave him a new one. Prescott will make more than 10 times his playing salary in endorsements this year.

A dinner with Al Carey, PepsiCo’s North American CEO, is emblematic of the new paradigms Prescott entered this offseason. They dined at a tony Dallas steakhouse, Town Hearth, where Carey was struck by the fact that Prescott earned a master’s degree in workforce management at Mississippi State after getting an undergraduate degree in educational psychology. Prescott told Carey his post-NFL career plans include getting a doctorate in psychology, as he wants to work to help athletes reach their potential.

Carey walked away from dinner impressed enough that he compared Prescott – “he’s that kind of person” – to longtime PepsiCo partners Peyton Manning and Derek Jeter. Prescott will star in national Pepsi commercials starting in October, will be featured in the brand’s social media and also be in the supermarket aisles.

“If you have young kids in sports,” Carey says, “I can’t think of a better role model than Dak Prescott.”

Cowboy stars tangoing with off-field trouble has long been part of franchise lore. A book chronicling the Cowboys glory days is called, “Boys Will Be Boys.” That’s why Cowboys officials note Prescott’s ability to handle the crucible of Dallas so deftly. (A DUI arrest soon before the draft hurt Prescott’s stock. He was found not guilty and cleared of all charges, but the pre-draft damage was done).

Prescott’s offseason contrasts sharply with Elliott’s. The running back was involved in an altercation at a nightclub. His six-game suspension comes from an unrelated incident and looms as one of the biggest stories of the first half of the NFL season. Cowboys coach Jason Garrett told Peter King of the MMQB that Elliott has cost himself significant money: “What would you do right now? You’d probably say if you’re one of those companies, ‘Oh, we’ll go with Dak. Or we’ll go with Jordan Spieth.'”

Cowboys COO Stephen Jones compliments the way Prescott has supported Elliott “hand-in-hand” this offseason and notes Prescott’s professionalism outside the Cowboys’ facility. From the time he’s been drafted, Jones says Prescott has been a model citizen. “Ninety-nine percent of the credit goes to Dak,” Jones says. “Very few people seize opportunities the way he did. He wasn’t given anything. He seized the moment from the day he walked in the door.”

****

A few hours after Prescott ran his football camp in Haughton, he’s sitting in the back of an SUV headed to an appearance. He’s asked to quantify how drastically his life has changed, and the question makes him pause.

“Damn. How do I?” Prescott searches for answers and starts with the run of kids camps, as more than 3,000 participated in Starkville, Haughton and Dallas.

A few minutes later, he’s asked what stood out about his rookie season, the type of frozen moment he’d tell his grandkids about someday. He paused again, showing how little time he has taken to reflect. Prescott then goes long on one of the Cowboys’ season-defining moments – Romo’s raw speech in mid-November when he conceded both his career mortality and the starting job. The speech is considered a Cowboys passing of the guard, a franchise quarterback anointing the next one. “That was a sense of like, ‘Damn, this is real now,” Prescott says. “This is my team.”

And with an entire offseason of being able to lead, Prescott says the “sense of uncertainty” that followed his status most of his rookie season is no longer there. That’s allowed Prescott to evolve from the leader of the Cowboys’ rookies in the offseason of 2016 to a team leader with veterans Dez Bryant, Jason Witten and Sean Lee. “I’d be remiss if I didn’t compliment just how deferential Dak was to Tony,” Jones says. “You never saw any air of Dak not being totally respectful to Tony, and that’s how he won everyone over. Everyone had so much respect for how he handled the situation.”

To keep that respect, Prescott designed his offseason to make sure none of his off-field ventures would get in the way of on-field pursuits. Dak the brand, in other words, couldn’t take precedence over Dak the player.

The roadmap for that gameplan hangs on the wall of Miller’s office in Scituate, Massachusetts. There are five months of oversized calendar pages mapping out Prescott’s offseason with a clear priority – keeping football first. Miller’s scrawl has calendar days dedicated to “AT&T” or “ESPYS” worked around OTAs. It wasn’t lost on the Cowboys brass that Prescott managed perfect attendance, as Prescott insisted he couldn’t miss a single weight-lifting session. It’s a prime reason why he won one of the team’s offseason MVP awards in the weight room, a rarity for quarterbacks.

Jones says there’s plenty for Prescott to work on, specifically mentioning getting rid of the ball quicker. (The luxury of such a stout offensive line allowed Prescott to hold the ball for long stretches in 2016). “The higher you climb up the flagpole, the more your ass shows,” Jones says with a laugh. “And he knows how that goes. He’s relentless in his pursuit of excellence, has an insatiable appetite for it.”

As a final salvo to offseason dedication, Prescott spent the last week before training camp in Orlando working with Tom Shaw, a football-specific trainer at Disney Wide World of Sports. While much of the NFL got last call in Cabo or Vegas, Prescott was already back to work. “He never stops,” Shaw says. “The best players wake up and the most important thing in their life is to get better at what they’re doing. That’s Dak.”

****

The poolside dominoes game back on the outskirts of Shreveport eventually mushrooms into an impromptu reunion. As the afternoon fades to evening, at a casino pool beneath the I-20 on-ramp, word spread through town that Dak is back. A collection of former high school friends, coaches and teachers stop by. They come from everywhere – the classroom, the oil fields and even the Waffle House. They come in greased-up work uniforms and hospital scrubs. They hoist perspiring drinks, toast their old friend’s ascent and laugh and dance until dark on a steamy Wednesday afternoon. “What I’m proud of is I still hang out with all these guys, just like I would if we were emptying Dumpsters,” he says. “We’re still playing dominoes.”

As evening gives way to night, the daily temptations that an NFL star faces float in. Calls and texts light up the cell phone of Prescott’s friends with offers of bottle services and cash appearances at clubs around town. It’s a small window into the constant tug that comes with stardom – thousands of dollars just to show up and the status of being able to roll with a big crew of friends for a night out. There’s discussion and debate about the competing offers, but Prescott ends up declining.

He wraps up his day like it started, surrounded by the crew of his closest friends. They retreat to the backroom of a steakhouse for dinner, the laughter, trash talk and revelry flowing deep into the night. “Nothing has changed,” he says again. “As much has changed externally, nothing has changed internally with me and my friends. That’s been the most important part to me.”

More NFL on Yahoo Sports