Seven events. Seven golds. Seven records. 50 years ago, IU's Mark Spitz became an icon.

Editor's note: This story was originally published in 2022. We are republishing it as part of our fall coverage.

BLOOMINGTON – Fifty years ago, there was a before-and-after Olympic Games.

After: The darkest moment in recorded sports history, terror and tragedy ending splendor and joy of Munich 1972.

Before: It was the Mark Spitz Olympics.

Seven events. Seven gold medals. Seven world records.

The seventh came in the 400-meter medley relay. It was Sept. 4, 1972.

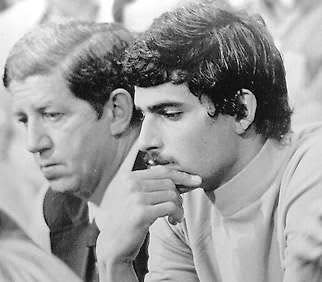

Witnessing it was Bob Hammel, then a 35-year-old journalist from the Bloomington Herald-Telephone, by far the smallest U.S. newspaper to have a credentialed reporter there. What he called a stroke of luck led to an exclusive interview — the only one Spitz granted during his Olympic swims — with the most famous man on the planet.

By then, the swimmer had five gold medals, then the most ever by any athlete at any Olympics. Five was one more than swimmer Don Schollander won at Tokyo in 1964.

“I was able to get back and talk with him at a time he had 40 minutes under a heat lamp and had nowhere else to go. The idea of talking to someone he knew all of a sudden had some charm,” Hammel said.

Spitz told him the public would not remember Schollander. Spitz said everybody remembers Jim Thorpe and Jesse Owens.

“He didn’t continue to say that’s who he’d like to be, but that was implication. It all held up extremely well,” Hammel said.

It did.

***

If not for epic failure at Mexico City four years before, Spitz would not have had epic success at Munich. And in one of the strangest twists in college sports history, Indiana University’s greatest athlete was not recruited by IU.

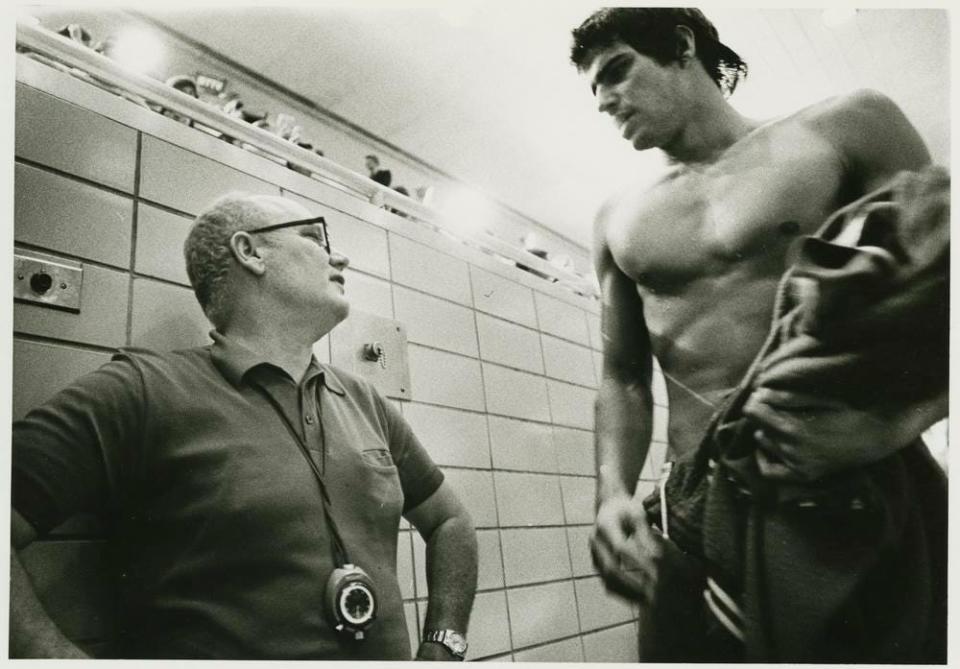

After the 1968 Olympics — where Spitz failed to win an individual gold medal — the 18-year-old Californian toured South America with other U.S. Olympians, including a teammate from the Santa Clara Swim Club, Mitch Ivey. Ivey wanted to transfer from Stanford, and the school he spoke about most was IU. Spitz remembered the camaraderie of the Hoosiers from the pre-Olympics camp but did not know a lot about coach Doc Counsilman.

Coincidentally, Spitz’s flight back from South America included a layover in Miami, and the Hoosiers were training nearby in Fort Lauderdale. He showed up at Counsilman’s hotel room, announcing to the coach he would not enroll at Long Beach State, as planned, and would go to Indiana.

“I ended up having the most marvelous years at Indiana University. And that helped my own confidence immensely,” Spitz said in a new 53-minute documentary by the Olympic Channel.

In four college seasons, Spitz won eight individual NCAA titles. As he was a perfect 7-of-7 in Munich, the Hoosiers were a perfect 4-of-4 in NCAA team championships.

Spitz was a frequent visitor to the home of Counsilman and wife Marge, as were other Hoosier swimmers.

“Mark was an interesting blend. He really did have an appreciative side,” Hammel said. “But he masked it well. He cared about his team. Really grateful to Doc and Marge.”

For the Olympic Channel, Spitz returned to Munich. He spoke candidly, and in detail, about what happened there and what led up to it.

Munich Olympics: Mark Spitz gave 'greatest athletic performance' longtime sports journalist Bob Hammel ever saw

The Mexico City memory “haunted” him, he said. Before those Olympics, he was on the cover of Sports Illustrated. There was talk of four, five, even six gold medals. He held world records in the 100- and 200-meter butterfly, after all.

“As it turned out, it was a catastrophe,” Spitz told the Olympic Channel.

Doug Russell, who had lost to Spitz in nine previous races, won the 100 butterfly in an Olympic record of 55.9 seconds. Spitz took silver in 56.4.

Spitz remembers Russell signaling No. 1 with his finger to the rest of Team USA.

“It was shocking,” Spitz said. “And I was thinking, ‘I’m the fastest in this event on the planet. I can’t believe this is happening.’“

By then, he said, he was feeling sorry for himself. He made the final of the 200 butterfly, and he swam dead last.

“It was my worst moment in my life. And I can remember that as if it happened six hours ago,” he said. “And we’re talking 54 years ago. I was devastated.”

***

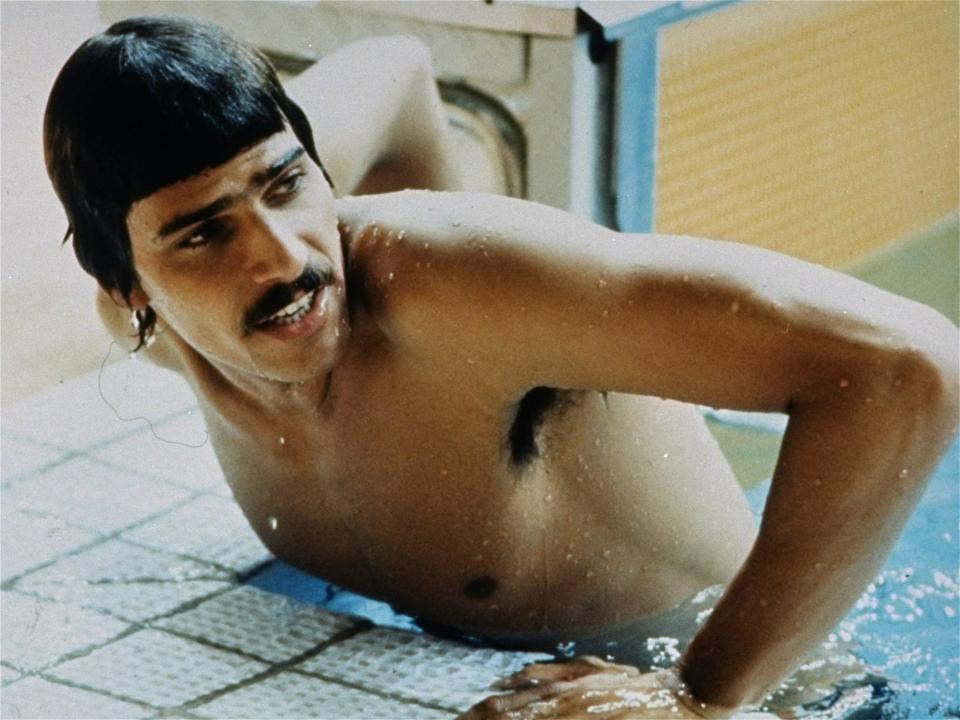

Upon arrival in Munich, the talk was not about Spitz’s swimming. It was about his moustache.

He conceded he grew it to spite Counsilman — “you’re not telling me what to do now” — and planned to shave it off before his first race. The “ultimate psych” job, he called it.

Swimmers customarily shave body hair before important meets to reduce drag in the water. For a swimmer to have a moustache was, well, ridiculous.

So he was asked about it.

“I don’t know why I said this,” he told the Olympic Channel. “I said, ‘No, I’m not going to shave it off. Matter of fact, it allows the water to deflect off of my mouth. I can get much lower and streamlined, get my behind up a little bit more. That’s why I broke the world record in the butterfly events at the Olympic Trials four weeks ago.”

It was utter nonsense. It was Mark Spitz in Munich.

“I’m going to keep it going, man,” he said.

***

The 200 butterfly was Spitz’s least favorite event, but he talked himself into thinking it was best to swim it first. U.S. coach Peter Daland of USC suggested the 200 fly would set a tone for the entire team. Spitz conceded winning could springboard him into history, and losing could derail him as it did four years before.

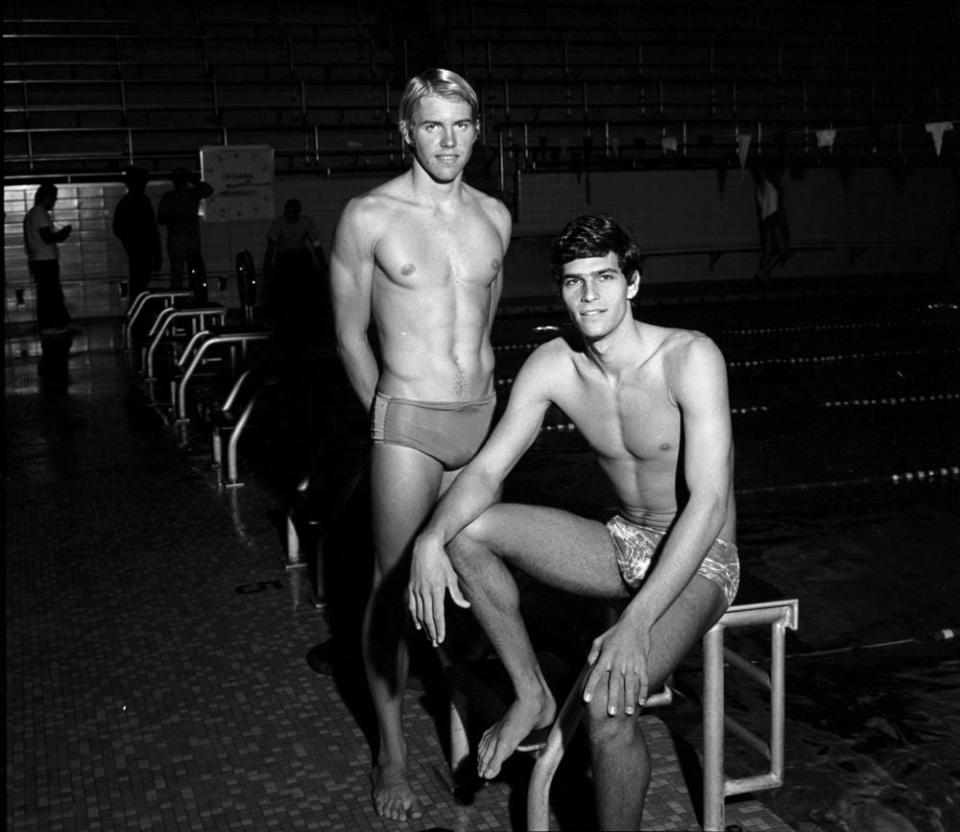

He had the presence of mind to close the sliding door separating the adjoining rooms between himself and Gary Hall, his roommate during IU road meets and a top contender in the 200 fly. Hall said he understood. The fact IU teammates like Hall actually did understand made all the difference.

Spitz was confident going into that first final. Then it happened.

He told the Olympic Channel “it was just like a movie” in which he felt he was back in the pool at Mexico City.

Oh no. Not again.

In his mind, Spitz said, he traveled elsewhere. He was not in Mexico City. He was not in Munich.

He was in Sacramento. It was there he said, he had actually bettered a world record during a workout before the Olympic Trials. When he dove in that Munich pool, he said, he imagined himself swimming in water in the middle of a California cornfield.

“The lesson I learned from Mexico City was, my destiny wasn’t a matter of chance. It was a matter of choices that I had to make,” Spitz said. “It wasn’t something that was going to happen by accident. It was going to happen by my sheer determination.”

At 50 meters, Spitz already led by three-fourths of a body length. He lowered the world record to 2:00.70, a time so fast even Hall, accustomed to Spitzian feats, was astounded. In an era in which world records fell regularly, this one lasted nearly four years.

It was Spitz’s first individual gold medal, something he had sought all of his life. He said he felt more relief than satisfaction.

“After I won my first individual medal in Munich,” he said, “I sort of forgot everything that happened to me in Mexico City.”

That night, he won another gold medal with another world record, 3:26.42 in the 400 freestyle relay. Ominously, Jerry Heidenreich’s third leg (50.78) was faster than Spitz’s anchor (50.91).

“The next day, this became my pool. I owned it,” Spitz said.

Pre-race drama involving his next event, the 200 freestyle, was not about him but about rival Steve Genter. The UCLA swimmer developed a collapsed lung on the charter flight to Munich. Five days before Genter’s Olympic debut, he had surgery that allowed the lung to expand to normal. At risk to his own health, he rehabbed all night and was able to raise his right arm, despite the 13 stitches.

Spitz led through 50 meters but was overtaken by Genter at the midpoint and still trailed at 150. Genter’s stitches had ripped open at the second turn, but not until 25 meters remained did Spitz pass him for good. Spitz lowered the world record for a fourth time, to 1:52.78, and beat Genter by nearly a full second. It was Spitz’s third gold in two days, overcoming Genter’s against-all-odds swim.

The post-ceremony drama was nearly as intense as that of pre-race. Spitz grabbed his worn Adidas shoes afterward — “my good luck shoes,” he said — without having time to slip them on. Then, holding the shoes, he waved at fans from the medals podium. The Russians complained Spitz was endorsing the shoes in violation of amateurism, and he was called in front of the International Olympic Committee’s eligibility committee.

Spitz said he never feared he would be kicked out of the Olympics. He was scolded, and that was it.

“The fact is, I had to compartmentalize every single day, and then seal it off, win lose or draw,” he said. “Move to the next day.”

***

Spitz’s parents, Arnold and Lenore, traveled to Munich as any other tourists would. They bought their tickets and commuted from Garmisch, Germany, or 55 miles from Munich.

They were interviewed on German TV, and the mother mentioned where they were staying. The head of the opposition party to Chancellor Willi Brandt heard the telecast and arranged to have the Spitzes seated in the VIP section with heads of state. And the commute became much shorter.

“Honest. I’ve got a helicopter,” Arnold Spitz told Hammel.

So Spitz often glimpsed his parents in the Schwimmhalle, they sat so close to the action.

***

After a day of heats and semifinals, Spitz had two gold-medal chances Aug. 31 — 100 butterfly and 800 freestyle relay. His fly nemesis, Russell, had retired after the 1970 NCAAs.

But there was ample competition: East Germany’s Roland Matthes, better known for backstroke; Canada’s Bruce Robertson, who equaled Spitz’s time in prelims; and the other Americans, Heidenreich and Dave Edgar.

Edgar started fastest but was overtaken at the turn by Spitz, who built a lead of half a body length. Spitz broke the 100 fly world record for the seventh time, to 54.27, followed by Robertson and Heidenreich. It was Spitz’s fourth gold, tying Schollander’s record.

Spitz called the 100 butterfly his revenge swim because it was that loss in Mexico City sending him on a downward spiral.

“He was real candid about how big that race was to him,” Hammel said.

In the relay, the Americans led off with Spitz’s IU teammate, John Kinsella, who was slightly behind the Soviets. The United States trailed West Germany through two legs, but Genter’s 1:52.72 third leg gave anchorman Spitz a lead of more than two body lengths. Genter’s leg was fastest of the race, even faster than Spitz’s world record (albeit with a rolling start).

The time of 7:35.78 broke the world record by an astounding eight seconds.

Four days. Five gold medals. Five world records.

“My biggest regret was I didn’t take enough time to enjoy it while it was happening,” Spitz told the Olympic Channel. “I couldn’t have. Because had I done that, I would have been a spectator to my own spectacle.

“And that happened to me four years before in Mexico City. I can’t advocate that the only way to be successful is to stay super-focused, but that’s exactly what you have to do.”

***

After nine races in four days, Spitz’s load would be light thereafter: three 100 freestyles and leg of the 400 medley relay over four days. Time off made him fretful, though. What if he lost in the 100 free? Better to be 6-for-6, right? Heidenreich was fast enough to beat him, and Spitz knew it.

After he told Daland he might not swim the 100 free, the U.S. coach approached Sherm Chavoor, coach of the women’s team and one of Spitz’s former coaches.

According to Spitz, Chavoor told him:

“You’re going to swim that damn event because nobody is going to recognize you as the best swimmer in the world unless you win that event — because that was the premier event. There were 15 contested men’s events. You could win 14 gold medals, Mark, but if you don’t win that gold medal, you are not the fastest swimmer in the world.”

Spitz replied:

“Well, you got a point.”

In prelims and semifinals, Heidenreich and Australia’s Mike Wenden, the defending Olympic champion, were both faster than Spitz. Yet in the final, in contrast to anxiety in the ready room of four years before, Spitz sensed the others were worried about him.

Spitz had held back in earlier swims. Not now.

“Because I wanted to put the pressure on the other guys,” he said. “If I was going to lose, they were going to have to catch me.”

He was ahead as early as 15 meters, leading at the turn over Heidenreich and the Soviet Union’s Vladimir Bure. The Russian drifted to the right side of lane 2 to take advantage of Spitz’s draft. Spitz moved to the center of lane 3 to foil that tactic. He lost rhythm near the end but reached the wall a half-stroke ahead of Heidenreich. Wenden, having over-trained in Australia, was fifth. Spitz’s time was 51.22, making it 6-for-6 in world records.

Heidenreich, who took silver in 51.65, was disconsolate. Winning this gold had been a life’s ambition since his parents moved the family from Terre Haute to Texas in the late 1940s so he could swim year-round. Heidenreich won four medals in Munich, two of them gold in relays, in a career so decorated that he wound up in the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Heidenreich, at age 52, committed suicide in 2002, a year after suffering a stroke.

Spitz and Heidenreich shared the pool once more, in the climactic 400 medley relay. Matthes tied the world record in the opening 100 backstroke to give East Germany a lead over Mike Stamm, another Hoosier. But breaststroker Tom Bruce put the Americans in front before Spitz’s butterfly leg, and Heidenreich’s freestyle anchor completed a world record of 3:48.16.

It was finished.

Seven events. Seven gold medals. Seven world records.

“It’s kind of hard to believe. I, I don’t know,” he said in a TV interview at the time. "Some day I’ll wake up and realize what I’ve done.”

Stamm and Bruce twice lifted Spitz onto their shoulders. Spitz had wanted to swim the freestyle anchor leg, capping his perfect Olympics. He agreed Heidenrich should have done so.

Michael Phelps’ eight golds at Beijing in 2008 eclipsed Spitz’s record. When it comes to dominance, though, a case could be made Spitz’s achievement was greater.

Spitz’s closest race in Munich was in the 100 freestyle, in which the margin was .42. Phelps famously won the 100 butterfly by .01, lunging at the finish, and took gold in the 400 freestyle relay because of Jason Lezak’s for-the-ages anchor swim.

To conclude the documentary, Spitz said he remembered his father telling him what he often did: Don’t let this all go to your head.

“Because I was just an ordinary guy that trained — hard, diligently,” he said. “And on one particular week, did extraordinary things.”

Then he teared up, showing emotion he had not allowed himself 50 years before.

Contact IndyStar reporter David Woods at david.woods@indystar.com. Follow him on Twitter: @DavidWoods007.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: IU swimming's Mark Spitz reflects on 1972 Munich Olympic