Queens of the Court: Black women tennis pioneers paved way for modern superstars

In February for Black History Month, USA TODAY Sports is publishing the series “28 Black Stories in 28 Days.” We examine the issues, challenges and opportunities Black athletes and sports officials continue to face after the nation’s reckoning on race following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. This is the third installment of the series.

Traci Green, women’s tennis coach at Harvard University, remembers when her father took her to see Zina Garrison play at the U.S. Open.

Garrison was the first Black woman to reach the finals of a Grand Slam tournament in tennis’ modern era. “I was about 10, and I had never seen a pro match or Black woman professional before up close. A couple of years later, I met Zina and Katrina Adams and hit some balls with them,” Green said. “Had I not seen Zina, Lori (McNeil), Katrina and Chanda (Rubin) frequently and up close, I don’t think I would have fully believed there was space for me in tennis and that I truly belonged. Representation matters.”

Green’s journey from starry-eyed Philly kid to one of the winningest coaches in Harvard women’s tennis history reflects the kind of inspiration that has catapulted many Black women into competitive tennis. Today’s tennis superstars Cori “Coco” Gauff and Naomi Osaka saw themselves in Serena Williams. Madison Keys was 4 years old when she spotted Venus Williams’ dress on television and decided she wanted to play tennis, too.

In fact, Black women in tennis have been nurturing and encouraging each other for more than 100 years. The lineage of Black women in the sport extends from pioneers in the early 1900s to world-renowned 21st-century players such as Gauff, Osaka, Keys and Sloane Stephens.

“Black tennis in America has always been strong and has always been competitive at a high level,” said Adams, a former pro player and the first African American president of the United States Tennis Association, the sport’s national governing body. “We just didn’t have the opportunity to play against everybody else who didn’t look like us.”

Pioneers

Less than 50 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Blacks who had accumulated any semblance of wealth sought to flaunt their brand of high society. Tennis provided quite the flex.

During the Great Migration, millions of Black people moved from the South. Many came to Chicago, bolstering its African American middle class and creating an upper class. Among the most notable was Mary Ann “Mother” Seames, a savvy businesswoman considered the mother of Black tennis in Chicago.

Seames reportedly started playing tennis in 1906. She hosted tournaments and soirees on grass tennis courts on her property. In 1912, she headed a small group that formed the Chicago Prairie Tennis Club.

In 1916, trailblazer Lucy Diggs Slowe was one of the founding members of the American Tennis Association, the oldest Black sports organization in America.

Slowe was as fearless in the classroom as she was on a tennis court. In 1904, she became the first female graduate from the Baltimore Colored School and the first from the school to get a scholarship to Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1917, Slowe won the first ATA National Championship.

She was also a founding member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority and the first dean of women at Howard University. She would later help organize the National Council of Negro Women and become its secretary.

Slowe and others formed the ATA to counter the United States National Lawn Tennis Association, now the USTA, which barred Black and brown players.

Regarding the ATA, “It was started by doctors, lawyers and businessmen, the upper crust of the Black community,” said Roxanne Aaron, president of the ATA. A 1939 Time magazine article emphasized that same point, noting that the ATA governed more than “150 Negro clubs and 25,000 players but also gives upper-crust Negro doctors, lawyers, teachers, preachers a chance to shine socially.”

Early royalty

Tennis great Arthur Ashe once told The New York Times that Ora Washington may have been the best female athlete ever. Washington dominated in both tennis and basketball, earning her the title “Queen of Two Courts.”

“Queen Ora” once scored 38 points in a game at a time when many women’s basketball teams would finish a game with 35 total points.

Washington stood 5-foot-7 but lacked proper tennis technique, holding the racquet halfway up its shaft. Yet she was strong, agile and quick. Her footwork, honed on the basketball court, was unmatched and allowed her to chase balls and win points.

Washington was inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2009 and the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018.

She won eight ATA national women’s singles titles between 1929 and 1937. She wanted to compete against Helen Wills Moody, winner of 19 Grand Slam singles titles and the woman the white tennis world considered the best. However, Moody refused to play her.

While Washington ruled in singles, two sisters from Washington, D.C., Roumania and Margaret Peters, swept through doubles. Nicknamed “Pete and Repeat,” the Peters sisters won 14 ATA doubles titles in 15 years, beginning in the late 1930s.

They were bona fide sports celebrities. Blacks and whites traveled to see them play. During World War II, the famed actor, dancer and tennis fan Gene Kelly was stationed at a naval base in Washington and stopped by to watch the sisters play, even joining them in a game. Younger sister, Roumania, also won ATA singles titles in 1944 and 1946, defeating the legendary Althea Gibson for the 1946 championship.

Washington and the Peters sisters never had a chance to test their talent against their white counterparts.

More: Pro women's tennis players, golfers top Forbes' list of highest-paid female athletes

More: 'Succession' spoilers? New careers? Serena Williams, Brian Cox talk new Super Bowl ad

Gibson, though, got that opportunity.

Board members of the ATA approached the National Lawn Tennis Association about getting a wild card tournament slot for Gibson.

“There were always other great players, even in football, baseball or basketball. But they’re not the person for the time,” Aaron said. “When you look at Jackie Robinson, there were a lot of Black players better, but he had the personality to withstand all the adversity.”

White fans booed Gibson, sometimes even throwing things at her. “She came out with her head held high,” Aaron said.

Gibson won five Grand Slam singles titles from 1956 to 1958 while in her 30s. “Who knows how many titles she’d have if she were allowed to compete (earlier),” Adams says.

Game changers

Tennis’ “Open era” began in 1968, when professionals were allowed to compete in Grand Slams. Despite Gibson’s earlier successes, though, the Open era seemed closed to Black women until 1981, when Cleveland native Leslie Allen won the Avon Championships. That tournament was the precursor to today’s WTA Finals, for the top-ranked players in the Women’s Tennis Association.

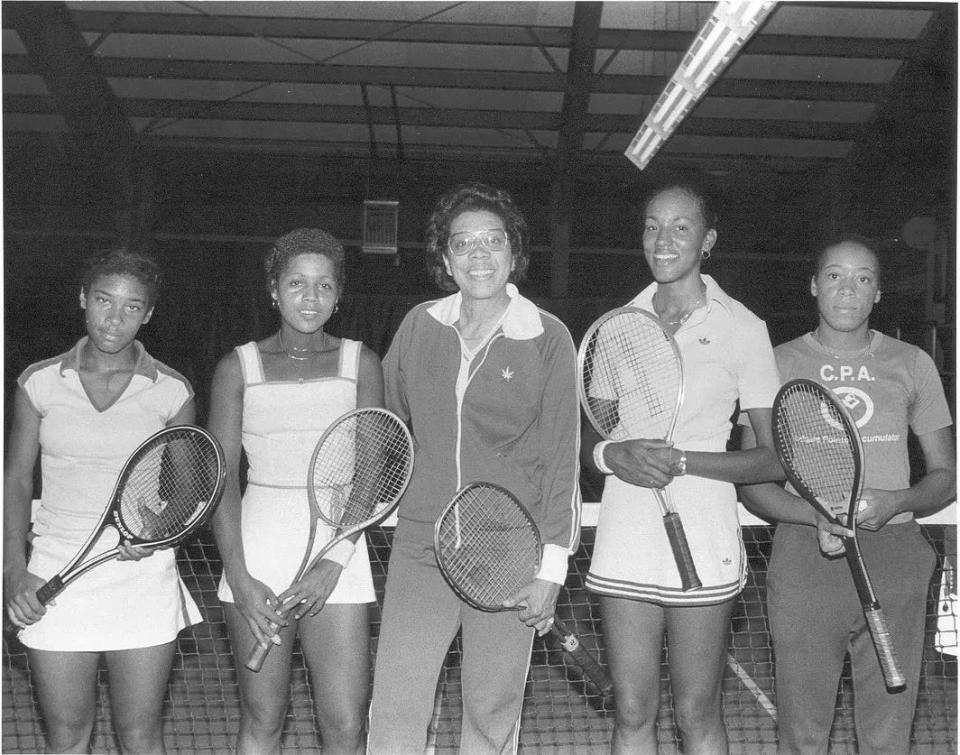

“As a WTA rookie, I was part of a training cohort with Althea at the Sportsmen’s Tennis Club in Boston,” Allen told WTA’s news site WTXtennis.com in 2021. “Althea asked each of us – Zina Garrison, Andrea Buchanan, Kim Sands and me – about our individual tennis goals, and I said: ‘To be in the main draw of WTA Tour events.’”

She recalled Gibson looked at her and said, “With your wingspan, you need to think about winning WTA tournaments.”

Allen described her 1981 victory as “akin to going viral today.”

“My victory was just what the WTA needed to increase visibility,” Allen told WTXtennis.com.

Joining Allen on tour were childhood friends Garrison and McNeil, who learned to play tennis at a public park in Houston.

In 1987, McNeil reached the Australian Open quarterfinals and the Wimbledon semifinals. A few years later, Rubin and Adams joined them on tour. “As soon as I came on tour, Zina Garrison took me under her wing,” Adams says.

Camaraderie came naturally. “That’s just the commonality you have, that you gravitate to those that you’re comfortable with,” Adams said. Among current players, “Sloane (Stephens) and Madison (Keys) are besties. In this sport, you’re coming up in juniors together. You know each other from an early age. ... That friendship is already there.”

In 1990, Garrison reached the finals at Wimbledon, the first Black woman to reach a Grand Slam final since Gibson.

McNeil reached the semifinals at Wimbledon in 1994.

Five years later, Serena Williams won the U.S. Open, the first of her record 23 Grand Slam titles. Venus Williams won the tournament the next two years on the way to seven career Grand Slam singles titles, and the complexion of the sport was forever changed.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black women’s tennis pioneers paved way for modern superstars