Purdue's first Black player lost to history: 'I thought he was mistreated and a lot of people did.'

Take a lap around the concourse of Mackey Arena and you’ll see the legends of Purdue basketball honored. Historic figures like John Wooden, Gene Keady and Glenn Robinson have images and short descriptions of their time and accomplishments in West Lafayette.

But there’s one historic figure in Purdue history missing. This is the story of Ernie Hall, Purdue's first Black basketball player.

Upbringing/Lafayette Jeff

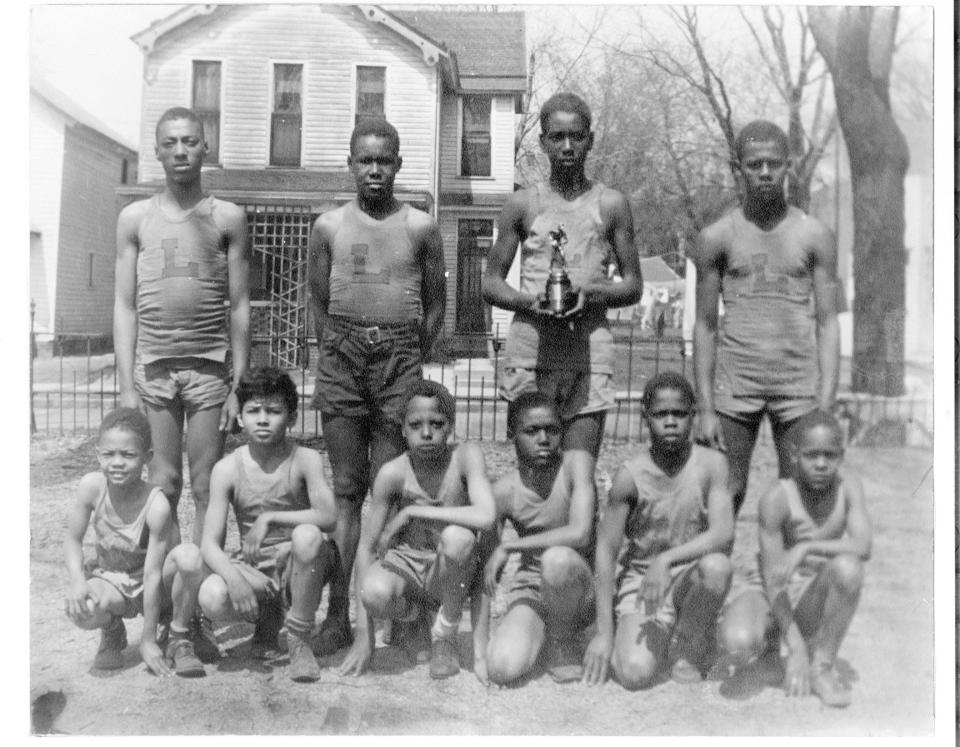

Hall was born in 1930 and raised in Lafayette in the midst of the Great Depression. He was born into a poor Black family and had at least 15 siblings. In Hall’s formative years, schools and most businesses were segregated in Lafayette.

In high school, Hall was taken in by Lloyd “Doc” Holladay, a local surgeon who also served as a physician at Lafayette Jeff High School. He became one of the first Black players on Jeff’s basketball team.

By his junior season in 1948, Hall started alongside four white seniors: Mr. Basketball winner Rob Masters, Dick Robinson, Bill Kiser and Charley Vaughan.

Hall — who stood only 6 feet, 2 inches — started at center. While there weren’t as many goliaths on the court in the 1940s as there are today, Hall was still undersized for a big man. His superb athleticism gave him a chance against the trees.

“He could out-jump everybody,” said Richard Bossung, a 1954 West Lafayette grad who watched Lafayette Jeff games and practices as a grade school student. “He was quicker than heck, and Jeff had good players that could get the ball to him and he could score.”

Often playing in a packed gym, Hall dazzled fans with his above-the-rim finishes, although he wasn’t allowed to dunk in games. Hall’s post play helped the Bronchos to a 17-3 regular season record and North Central Conference championship.

Hall was generally accepted by his teammates, coaching staff and classmates, but the same couldn’t be said for those outside the community.

When the team was on road trips and needed a bite to eat, coach Marion Crawley walked into restaurants alone. Crawley — a 1964 inductee into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame — would ask if an establishment was willing to serve a Black man. If the answer was no, he returned to the bus and told the team the restaurant didn’t smell good and they should eat elsewhere.

“I caught on eventually,” Vaughan told IndyStar. “I never said a word about it, but I caught on kind of why he was going in there first.”

Hall prevailed through discrimination on and off the court throughout the Bronchos’ run in the 1948 state tournament. Lafayette Jeff rolled through its sectional and regional, with only one of its first six tournament games being decided by less than 10 points. In the one close game — a 45-37 victory in the regional final against Lebanon — Hall led all scorers with 17 points as the Bronchos overcame a five-point halftime deficit.

A week later, Hall scored 21 points to lift Jeff over Peru in a 60-53 semistate clash. The win earned Lafayette Jeff a spot in the state round for the first time in 27 years.

Hall and the Lafayette Jeff squad advanced to the four-team state championship in Hinkle Fieldhouse (then called Butler Fieldhouse) on March 20, 1948. All 15,000 seats in the fieldhouse were filled to watch Hall drop 18 points against Anderson in Jeff’s 60-48 win in the first game of the day.

The Bronchos gave a balanced effort en route to a 54-42 defeat of Evansville Central in the state championship. Hall scored 11 points, and his 29-point day ranked second among players on all four teams present. Lafayette Jeff won its first state title since 1916.

It was a glorious celebration for Hall, Crawley and the entire Jeff squad. Later that night, racism reared its ugly head again. The team reserved rooms at a hotel in Indianapolis earlier that week, but the hotel forbade Hall access when the team arrived after the game.

Hall returned for his senior season as the only starter to carry over to 1949. He led Jeff to another sectional title, but the team failed to escape the regional round this time.

Vaughan believes Hall would’ve won Mr. Basketball over Masters had Hall been a senior during the 1948 run.

Hall ended his high school career as one of the Bronchos’ all-time leading scorers. Lafayette Jeff won at least a sectional in all three years Hall was on the roster.

Junior College

Despite Hall’s decorated high school career, Purdue coach Melvin Taube did not extend an offer for him to play with the Boilermakers out of high school.

“I never could understand why I couldn’t play for Purdue,” Hall said in Ken Thompson’s 1998 book Most Memorable Moments in Purdue Basketball History.

Due to his lack of major offers, Hall went to play for Ventura College, a junior college in California. He was brought in by coach Elmer McCall, a Frankfort graduate who was inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame in 1973.

Hall immediately proved he belonged.

As a freshman, he led the nation in scoring. With Hall’s prowess, Ventura went 35-3 and won its first Western State Conference crown in program history.

Ventura repeated as conference champions in Hall’s sophomore season. The Pirates also conquered the Western regional tournament in 1951, which earned them a berth in the 16-team junior college national tournament in Hutchinson, Kansas.

He left Ventura as the school’s all-time leading scorer. His scoring record at Ventura wouldn’t be broken until NBA All-Star Cedric Ceballos surpassed him in 1988.

The return home

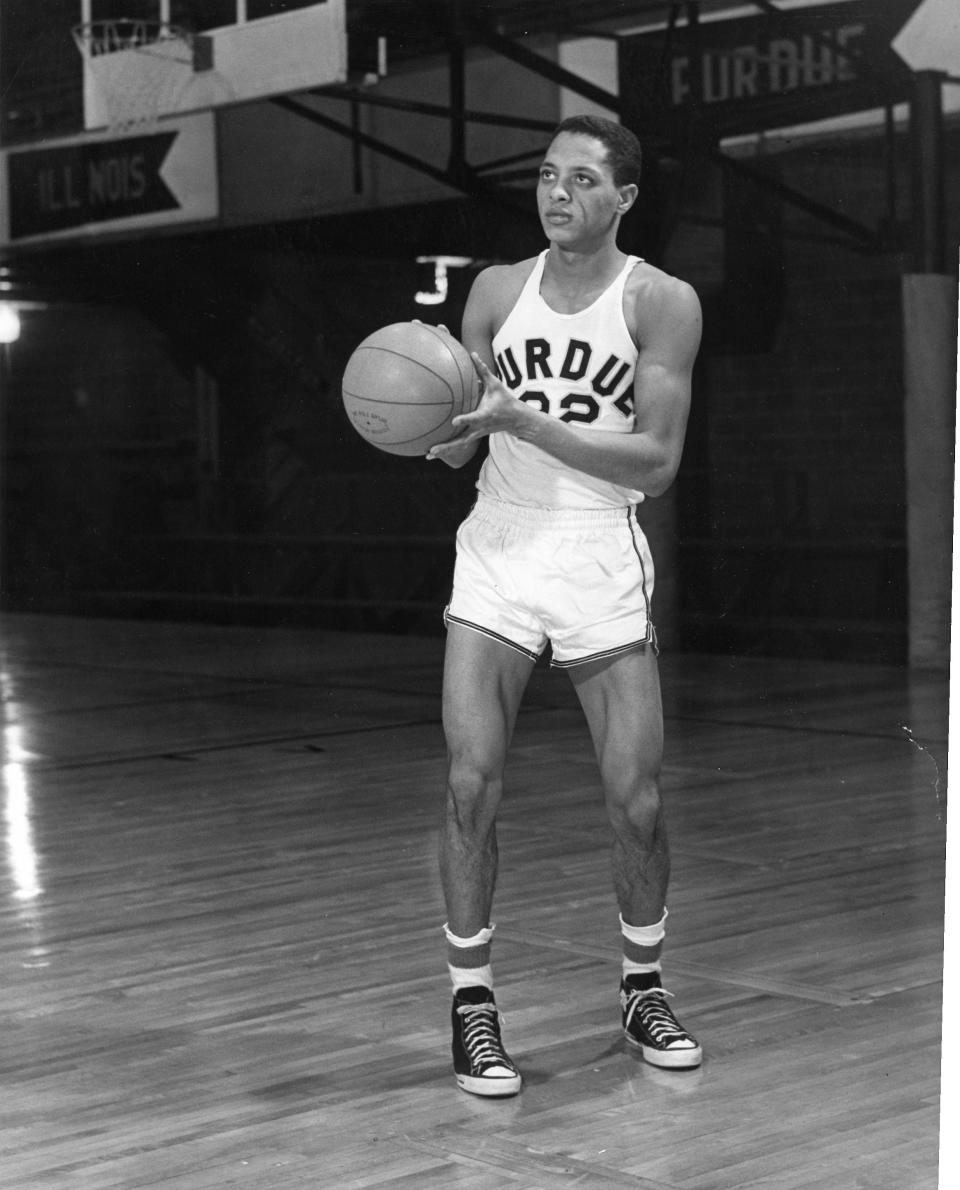

In September 1951, Hall did what he yearned to do out of high school. He enrolled at Purdue. In doing so, Hall became the first Black player — and JuCo product — to join the Boilermakers.

Hall returned home as a married man. From 1949-76, married students at Purdue were housed at Ross Ade I (now Hilltop) Apartments. This complex is less than a mile away and no more than a 15-minute walk from Lambert Fieldhouse, where Purdue played its basketball until Mackey Arena opened in 1967.

But Hall was not the typical married student at Purdue. Because Hall was Black, the university wouldn’t let him reside at the location that was within reasonable walking distance from the gym. Hall and his wife, Laura, lived at 1631 Tippecanoe St. on the east side of the Wabash River in Lafayette. This location is over two miles away from Lambert Fieldhouse and about a 50-minute walk away.

“This was not a very good section of Lafayette to be living in,” Vaughan said.

Despite his inconvenient living situation, it didn’t take long for Hall to show he could play Division I basketball. On Dec. 10, 1951, Hall logged 32 points in a win over Marquette. Marquette — a team coached by Tex Winter, the innovator of the triangle offense — had no answer for Hall in the third game of his Division I career.

“At that time, somebody getting 32 points in a game in college was a hell of an accomplishment,” Bossung said. “And he got it against a very good team. He had the talent, there was no question about that.”

Hall’s 32 points were the second-most points scored in Purdue history at the time. Hall stood behind only his teammate Carl McNulty, who scored 34 in a game the prior season. Hall missed two free throws late against Marquette that would’ve tied McNulty’s record.

Five days later, Hall dropped 26 points to lift Purdue to an 82-65 victory over No. 17 Louisville. It was one of Louisville’s six losses. Hall set a new Purdue record for points in consecutive games, scoring 58 in Purdue’s two wins.

As Big Ten play began in January 1952, Hall continued to shine. He opened conference play on Jan. 5 by leading Purdue with 23 points in a 79-64 win over Wisconsin. The win — which came in front of a crowd of 10,000 fans in Wisconsin Field House — lifted Purdue to 6-2 on the season after an 8-14 1950-51 campaign.

An abrupt ending

On Jan. 12, 1952, Hall scored six points in Purdue’s 85-83 loss at Northwestern. Northwestern limited Hall to a low-scoring night, but he scored a late bucket to give the Boilermakers a 77-75 lead.

Hall won a crucial jump ball when the score was tied at 83, only for it to be called off due to a Purdue player being illegally inside the halfcourt circle for the jump ball. Northwestern was awarded possession and scored a game-winning basket.

It would be Hall’s last game in a Purdue uniform.

The following night, on Jan. 13, Hall had an altercation with his neighbor Coy Monroe in Lafayette. Monroe — who was a 40-year-old Black man — claimed Hall (21 years old at the time) attacked him with a knife.

There were conflicting reports regarding where the fight occurred. While some reports say the fight happened at a house party in their neighborhood, others say it occurred at a tavern which was later identified as Al’s Barbecue, a Black-owned restaurant that was just north of Salem Street.

Monroe reportedly flirted with Hall’s wife, Laura, and Hall took offense. There are no extensive reports on what Monroe said or did to Hall’s wife, nor how exactly Hall responded.

“He goes there and somebody hits on his wife, and he ends up hitting the guy,” Vaughan claimed. “You would’ve thought it was the worst thing in the world.”

Hall was arrested at his home late that night and charged with battery and assault. He was released on a bond of $250, which equates to nearly $3,000 in 2024.

Purdue coach Ray Eddy immediately kicked Hall off the team. While speaking to the media before Purdue’s game the following day, Eddy said Hall had been dismissed “for violating training rules,” and did not elaborate further.

“Purdue decides immediately without trial and looking into all the circumstances or anything, he’s off the team,” Vaughan said in frustration. “That’s what they did. They ruled right then and there, he’s off the team.”

On Feb. 4, Hall was acquitted of both charges by the city. His defense team claimed he struck Monroe in self-defense, and Judge Mark Thompson said the state “failed to prove otherwise.”

Hall didn’t return to the Purdue roster after the acquittal. In his time fighting to prove his innocence, Hall was ruled academically ineligible. Some reports said Hall could’ve come back to Purdue in the fall, but it never actualized.

Vaughan blames Purdue for Hall having to live in a poor part of Lafayette as a college student.

“I think Purdue gave him a real bad deal,” Vaughan said. “They should’ve had him in the student housing, over there with other people, where he could socialize with a different crowd. But no, he couldn’t come.”

Aftermath

Following his removal from Purdue, Hall was drafted into the Army, where he served as an artillery sergeant. In his two years, Hall continued playing basketball. Hall frequently played games with the Special Services.

Once Hall was released from the Army, his college basketball career resumed. Hall enrolled at former Division II school Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, Calif.

At Cal Poly, Hall did what he had done everywhere: Score and win.

Upon Hall’s arrival, Cal Poly won its first two California Collegiate Athletic Association championships in 1955 and 1956. The Mustangs wouldn’t win another CCAA title until 1972 and to this day, the program has won only 10 regular-season conference championships.

Although most of Hall’s experience was as a big man, the 6-2 player became a guard during his time at Cal Poly. The position change didn’t stop Hall from setting single-season program records for points (423), points per game (16.7) and field goals (150) in 1956.

After graduating from college, Hall lived a secluded lifestyle. He settled in Oxnard, Calif., where he lived with his family. Hall worked for the U.S. Postal Service for decades, and Vaughan claimed he also spent time as a courtroom scribe.

Hall died of throat cancer at the age of 77 on Oct. 8, 2007. His death came just three days after Ventura inducted him into its Hall of Fame. Hall was too ill to attend the ceremony.

He was survived by his two kids, Kitty Thompson and Earl Hall. Earl won a 1999 California state basketball championship. Like his father, Earl was an undersized center on his team at 6-3.

“He showed me how to use what I had,” Earl told the Ventura County Star in 2007.

Hall rarely returned to the Lafayette and West Lafayette area, although he kept in contact with friends like Vaughan and Bossung. Despite his tremendous accomplishments in high school and college, Hall has never been honored individually in his home state.

Not at Lafayette Jeff. Not at Purdue. Not in the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame.

“He has never been to an event at Purdue after he was kicked off the team,” Bossung said. “He never went to a class reunion. He never went any place involving Purdue basketball. That's a shame because I thought he was mistreated and a lot of people did.”

Vaughan and Hall spoke frequently throughout the years. Vaughan would occasionally visit Hall in California, and Hall would return the favor in Lafayette. Vaughan said Hall enjoyed taking his boat to Santa Catalina Island in Los Angeles County in his free time.

“He always had a smile on his face, everybody liked him,” said Vaughan, a former lawyer at Vaughan & Vaughan in Lafayette. “Everybody in the school liked him, and he was just a good guy.”

Over 70 years since he played at Purdue, Hall’s legacy remains jumbled. He’s one of the best to ever play at Lafayette Jeff, but a scuffle with a man nearly twice his age marred Hall’s return home. Once Hall was kicked out of Purdue, folks back in Indiana seldom heard from him.

“He probably had more relationships with Ventura College than he did Purdue,” Bossung said.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Purdue basketball's first Black player Ernie Hall was kicked off team