Ghost Olympians: The lives forever changed by the 1980 boycott

Forty years ago, the United States boycotted an Olympic Games for the first and, to date, only time. This is the story of the aftermath of that decision – of the human lives the boycott forever changed.

Part 1: The saga of the 1980 boycott | Part 2: The lives forever changed

More: Robbed at the 1980 Olympics? | An American medals in Moscow | Muhammad Ali plays diplomat

On an innocuous spring day in 1982, two years after the boycott gutted him, and almost a decade after that mini-market newspaper spawned his Olympic ambitions, Jesse Vassallo bounded out of a Vancouver natatorium in search of fun.

He remained, on this Pacific afternoon, as optimistic as ever. His world record in the 400-meter IM was approaching four years untouched. His first year at the University of Miami had yielded an NCAA championship. He was one of hundreds of American athletes who were wounded by 1980. He was also one of hundreds who recovered and took aim at L.A. ’84.

Not a single one of their paths to Los Angeles was linear. Vassallo’s veered off course here, in Vancouver, in between prelims and finals at a second-tier meet. He and a few teammates snatched a pull buoy and slid out to a nearby basketball hoop to play. As the foam device caromed off the rim, Vassallo flexed his legs and sprung for a rebound. A teammate nudged him. When he landed, his left knee twisted and quickly swelled.

He consulted doctors and tried rehab. He even attempted to swim with a cast. He competed at nationals, but narrowly missed out on worlds. He watched from home as a Brazilian broke his 400 IM record.

He then went under the knife, and emerged with blood clots. He stayed hospitalized for 16 days. He spent several weeks in a wheelchair, then more on crutches. As 1982 became 1983, four months out of a pool became five, then six, then eight.

The Olympics remained a year away. Vassallo told friends he’d get there. Dozens of 1980 U.S. teammates did likewise – only to realize throughout the four years between Moscow and Los Angeles that dream fulfillment required more than just persistence. It also required fortune. And fortune frowned upon so many of them.

*****

In 1981, Susie Thayer graduated high school and zoomed off to the University of Texas on scholarship. She enrolled in pre-med classes and loved her new teammates. But internally, she was confused.

Back in high school, she’d been Susie Thayer The Athlete. She never had to be anything else. She didn’t go to dances, didn’t socialize, didn’t date. Norms and her Christian faith told her to be attracted to boys. Susie wasn’t. In fact, for as long as she could remember, she felt like a boy. She didn’t quite know what those feelings meant. But when she was pumping makeshift weights or powering through a pool, she didn’t have to grapple with them.

Now she was off at college, a thousand miles away from home. In the privacy of her dorm room, her mind swirled. Her own sexuality and identity perplexed her. Parts of her brain wanted to ask out a girl. Susie had no idea what to do, nor anybody she trusted for counsel. At swim practices, she butted heads with her coach. Away from them, she descended into dark places.

After freshman year, she decided to transfer closer to home. She packed up and spent the summer back in Florida. In the fall, she drove up to Auburn. She arrived to a rude awakening: Auburn’s head coach, the one she’d come to swim for, had taken the same job at Texas. The same Texas she’d just left.

Susie felt humiliated and lost. She didn’t last long at Auburn. She packed up again and motored home. This time, she told her parents she was done. With swimming. With school. Her parents were incredulous: How could you give up a full-ride!? But Susie had to get away. Part of her brain still wanted to swim. Another part of it knew she couldn’t.

*****

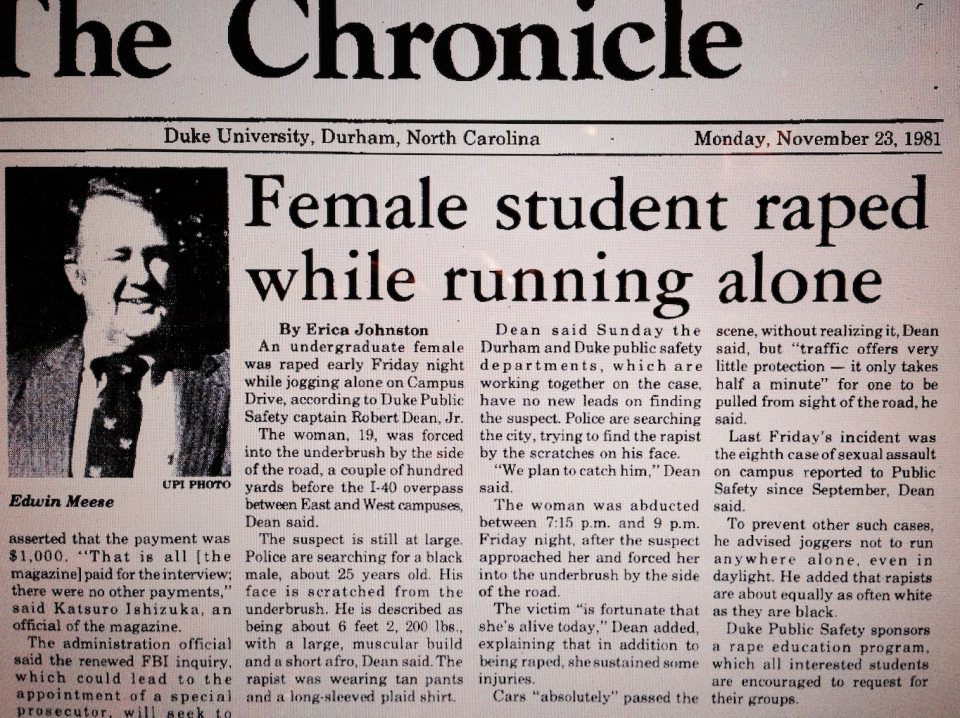

Nancy Hogshead roared through her freshman year at Duke in 1980-81, smashing school records as she went. The community welcomed her. The classes enriched her. The boycott was behind her. Year 1 of 4 was a success.

In the fall of her sophomore year, she was jogging between Duke’s East and West campuses when sirens inside her head began blaring. A man was running toward her. No big deal, she told herself, but darkness was falling, and she realized she was alone.

Suddenly, the man grabbed her and pulled her underneath an evergreen tree. In the underbrush, she fought for her life. He told her he’d kill her. She tried everything. He pulled her deeper into the woods. And he raped her.

She arrived at a hospital late that night shivering and bruised, her lips swollen, one eye forced shut. Hours later, sitting alone on an exam table, she vowed to not let the trauma define her life. But she soon realized she was no longer in control of emotions. Fear seeped into everything she did. She dropped classes. She compulsively checked windows and doors to make sure they were locked, again and again, several times each night.

Once she recovered physically, she hoped swimming could heal her; that the pool, and the rhythm of her strokes, and the feel of the water would put her mind at ease. Instead, whenever she hopped in, her mind would wander. Back into the woods. Back into survival mode. Back to that awful night.

Her coach advised her to take a year off. “You’re gonna come back, and you’re gonna win gold at the Olympics,” he told her. She couldn’t fathom anything of the sort. He called it a redshirt. She called it retirement.

*****

Rowdy Gaines quit. Unequivocally, after his senior season at Auburn in 1981, with ire toward the entire Olympic movement still lingering. There were no post-college careers in swimming. Olympic sports remained entirely amateur. So Gaines finished up school, did some lifeguarding, and plotted out next steps. He figured he’d follow his dad into the film business.

It was Dad, ironically, who wasn’t quite sure his son was ready.

“Are you going to be able to look yourself in the mirror for the rest of your life and not say, ‘What if’?” he asked Rowdy. “Are you gonna be able to listen to the national anthem? Are you gonna be able to watch an Olympic Games? Are you gonna be able to chant, ‘USA’?

“If you feel like you can, then let’s get busy trying to figure out what your career’s gonna be. But if you feel like you can’t go the rest of your life without looking in the mirror and saying, ‘What if I had gone for it?’ – then you need to think about dedicating the next three years of your life to swimming.”

Toward the end of the summer, Rowdy called his coach. They hadn’t spoken in six months. He hadn’t completed a single lap. But he wanted back in.

So he found a cheap apartment and a job in Austin. He took a 7 p.m.-3 a.m. desk shift at the local Hyatt. He’d crash at 3:30 and wake up at 5 to swim. Middays became bedtime. The day’s second practice began around 3 p.m. and stretched until 6. An hour later, after wolfing down dinner, he was back at work.

The upside-down routine wore at him. His college cocoon had disappeared. He had one roommate, no social life and no balance. His swimming suffered. His 200 freestyle world record vanished. After some punishing workouts, on some lonely nights, despite his coach’s relentless positivity, he pondered giving up.

Many athletes did give up in the four years between the boycott and Los Angeles. The strains of life proved too heavy. There was no money in their sport, and no room for training alongside full-time employment.

But whenever Gaines came close, his coach reminded him of the first conversation they’d had back in the summer of ‘81. “If you do this, you’re going to experience tremendous peaks and valleys,” he’d told Rowdy. “You’ve just gotta roll with the valleys, learn from them, and I’ll get you to the peak.”

By January of ’84, Gaines had saved enough paychecks to quit his gig at the Hyatt, and life normalized. He’d endured. Trials neared. He wasn’t the sprinter he once was. But at 25 years old, at last, the Olympics once again appeared on the horizon.

*****

Nancy Hogshead didn’t swim for months in 1982. When she returned to Duke in the fall, 10 months after the rape, her coach tempted her with a deal: You don’t have to come to practices. You don’t have to lift weights. You can keep your scholarship. Just show up at meets.

She hesitated, but accepted it. Her body ached after her first few races. But … she won them. Gradually, sometimes separately from the team, she began training again. With every stroke, she recaptured her grace. Every lap rekindled her competitive fire. Every session conjured a more vivid image of the Olympic rings. By Thanksgiving, they’d become vivid enough to chase again. Hogshead floated a plan to her parents: She wanted to give up her scholarship, drop out of school, go all in. They questioned her, but agreed to loan her money for rent.

At her first few practices, she gasped for air. But when she’d hop in a pool now, she’d regain control. In the water, she’d fight her rapist; but now, she’d win. Her mind’s adventures no longer frightened her; now, they healed her. By 1984, her biceps had recovered from a tumultuous year off; more importantly, her entire being had, too.

She and more than 30 of her 1980 teammates converged on Indianapolis in June for Olympic trials – and their vindication. Rowdy Gaines and Jesse Vassallo – who’d recovered from his knee reconstruction – were among them. Tracy Caulkins was as well. Caulkins, despite two years of lagging motivation, knew she’d make the team. Sue Walsh, an American record holder and back-to-back-to-back NCAA champion, seemed a sure bet too.

Then, on the eve of trials, Walsh got sick.

*****

One thousand, five hundred and thirty-six days after Rowdy Gaines set his first world record in the 200-meter free, and 1,535 days after that USOC vote made him wait four long years, he hunched over on a block in Indy ahead of the same event. His sun-bleached hair jutted in 10 different directions. His narrow eyes and taut face told of pressure.

The gun sounded and he dove in. He sprinted one length, then another, then a third, just like he had thousands of times over the past eight years. He labored over the final straightaway, head snapping in and out of water. A top-two finish would get him to the Olympics. He touched the wall and looked up.

He’d finished seventh.

Two days later, he’d have one more chance, 100 more meters, 50 seconds to justify the past three years of his life.

*****

Nancy Hogshead qualified in three of her five events. Jesse Vassallo qualified in two of his three. Tracy Caulkins blew away the field in both medleys and won the 100-meter breaststroke. In between her races, she agonized over others.

She watched 15 of her 1980 teammates qualify. But she watched Craig Beardsley, who’d smashed a 200 butterfly world record in 1980, miss out by .36 seconds. She watched Marybeth Linzmeier finish third by .41. Her own races brought relief. Theirs brought sorrow.

On June 27, she watched Rowdy Gaines fling himself into the water for his final shot, the 100 free. She watched three more youthful swimmers match him stroke for stroke, kick for kick, turn for turn at the midway point. They careened toward the wall neck-and-neck. They touched and emerged. The scoreboard delivered the news. Mike Heath: 49.87 seconds. Chris Cavanaugh: 50.04.

Rowdy Gaines: 49.96.

And in an instant, stress evaporated. Anger – boycott-induced anger – disappeared. Rowdy Gaines was an Olympian. A true Olympian.

*****

Sue Walsh, meanwhile, climbed into bed the night before the 100-meter backstroke with mucus swelling beneath her cheeks. She’d medaled at every major championship in her specialty event over the past four years. Now her sinuses were infected. In the morning, she swam well enough to make finals, but was struggling to breathe. Her head was clogged. Her muscles felt weak. The same pressure that had haunted Gaines, of eight years dependent on one minute, further weakened them.

She windmilled through the pool anyway that evening, eyes toward the heavens, elation or disappointment awaiting her at the wall. She reached for it and looked up. Then her head fell to the side of the pool. Tears gushed from her face. She’d missed out on an Olympic place by an unseeable .12 seconds.

Her dad, who’d booked a non-refundable trip to Moscow back in 1980, who’d supported her and loved her at every stage of the journey, made his way down to the pool deck.

Sue found him, they embraced, and for a long while didn’t let go.

“You’ll always be my champion,” he told her.

And then they left, to get away. Several weeks later, Sue returned to a pool. She told herself she’d continue training. A broken heart wouldn’t let her. She was one of 290 members of the 1980 team who never qualified for another Olympics. After trials in ’84, she never swam in elite competition again.

*****

A hundred-plus 1980 Olympians marched into the Opening Ceremony on July 28 to waving flags and chants of “U-S-A! U-S-A!” From the packed bleachers of the Coliseum, friends and family shouted their names. And they realized, many for the first time in their lives, that they were surrounded by thousands of humans who didn’t necessarily speak their language, who didn’t necessarily understand their culture, but who did understand 10,000 hours, and the psychology of mastery, and the unseen suffering behind athletic beauty. Their eyes welled and told the story speechless mouths couldn’t:

We’re here. Never mind that it took four extra years. They were worth it. Never mind that the Soviets have led a reciprocal boycott. We’re here. Finally.

Then they went in search of medals. On the first morning of competition, at prelims, Tracy Caulkins slithered through water and heard a roar unlike any she’d heard before. Prior to the 400 IM final that evening, excitement built. She huddled with her coach. She expected a galvanizing, emotional pep talk. About the years of dedication and the extended wait. About the opportunity that had finally arrived.

Instead, he kissed her on the cheek and said: “Trace, go have fun.”

And in that moment, she remembered something that had faded in 1982 and ’83, for her and many others. She hadn’t delved into this sport as an 8-year-old to win 48 national titles and break 63 American records. She hadn’t braved cold mornings and the discomfort of water in her nose because she wanted Olympic gold. She swam because she loved it.

That’s what she thought about as she sped ahead of seven others, as the stands at USC shook above her, as teammates who’d suffered through ’80 together urged her on. My goodness, this is fun. She finished in 4:39.24, a full nine seconds ahead of her nearest challenger. She stepped up to a podium. An official draped a medal around her neck.

She looked into the crowd and picked out her parents, the ones who’d driven hundreds of miles to every one of her swim meets. She saw her sister, and her high school PE teacher too. She waved. Hundreds of people she’d never met waved back. She didn’t need Olympic gold to make her the greatest female swimmer ever. Now she had it.

*****

Nerves seized Rowdy Gaines two days later. Ever since that seventh-place finish at trials, he’d been staring out over an emotional ledge. That next day in Indy, he’d sat with Caulkins in a hotel food court. “I believe in you, everything’s gonna be OK,” she’d told him then, and she’d been right.

But his confidence was shaken. Now, in L.A., his only individual final was hours away. His morning swim had been slow. What if I don’t win? he wondered, and part of him had come to terms with the eventuality.

Caulkins recognized this, and found him that afternoon. And on the day he’d spent eight years swimming toward, she tugged his mind back through the journey, the ups and downs, the grueling practices, the boycott. You deserve this, she told him. You deserve to be here. Regardless of how tonight shakes out, the sun will come up tomorrow. Your family will still love you. Life will go on. So cherish the moment.

Hours later, Gaines flapped his arms and forced a smile. He splashed water over his head. He anticipated a quick gun and shot into the water.

He stole out to an early lead.

He held it at the midway point.

He hugged the left lane rope over the final 50.

He lunged for the wall, and turned around, and plucked his yellow-rimmed goggles away from his eyes.

His right fist shot into the air. His entire torso sprung out of the water. Boyish happiness washed over his face. He threw his head back and stared skyward, then flung himself back into the water, half dolphin, half joyously rambunctious kid. Then he brought his hands to his cheeks in disbelief.

Eleven American swimmers who’d been impeded by the boycott won gold medals in 1984. Gaines was one of them. Nancy Hogshead was too. "This week, I kept thinking about all the workouts, all the time, all the pain," she told a reporter in Los Angeles. "I thought of the cold mornings. In winter, our outdoor pool gets a layer of ice on the deck. I thought of all the times I slipped on that ice. I thought of everything I gave up, all the friends I couldn't socialize with, all the pain I was in during workouts. All of it."

"Every one of these," she said of her four medals, three of them gold, "has been a highlight of my life."

*****

On July 30, in the 400 IM, the race he surely would have won four years earlier, Jesse Vassallo prepared to join the party. He’d shaved off his thick, shaggy hair. Now he wiggled his limbs and ascended to a block. He was slow off of it, then recovered. Over the second 100 meters, he pulled into second place with his backstroke.

Over the third 100, he slowed. Over the final 100, he fell back, three body lengths behind the leader, then four. He touched the wall fourth.

He reached for the lane rope, exhausted by four-plus minutes of toil but also by a decade of it.

He missed the final in his other event by .05 seconds the following morning. He bolted out of Los Angeles as soon as he could. He barely left his home for weeks.

And as he hid from a cruel world, frustrated, humiliated, depressed, he swore that neither he nor his kids would ever swim again.

*****

As devastating as 1980 was, 1984, for those who persisted then fell short, was more difficult. And many did just that. Even Susie Thayer attempted a last-minute comeback. But she couldn’t recapture her teenage speed.

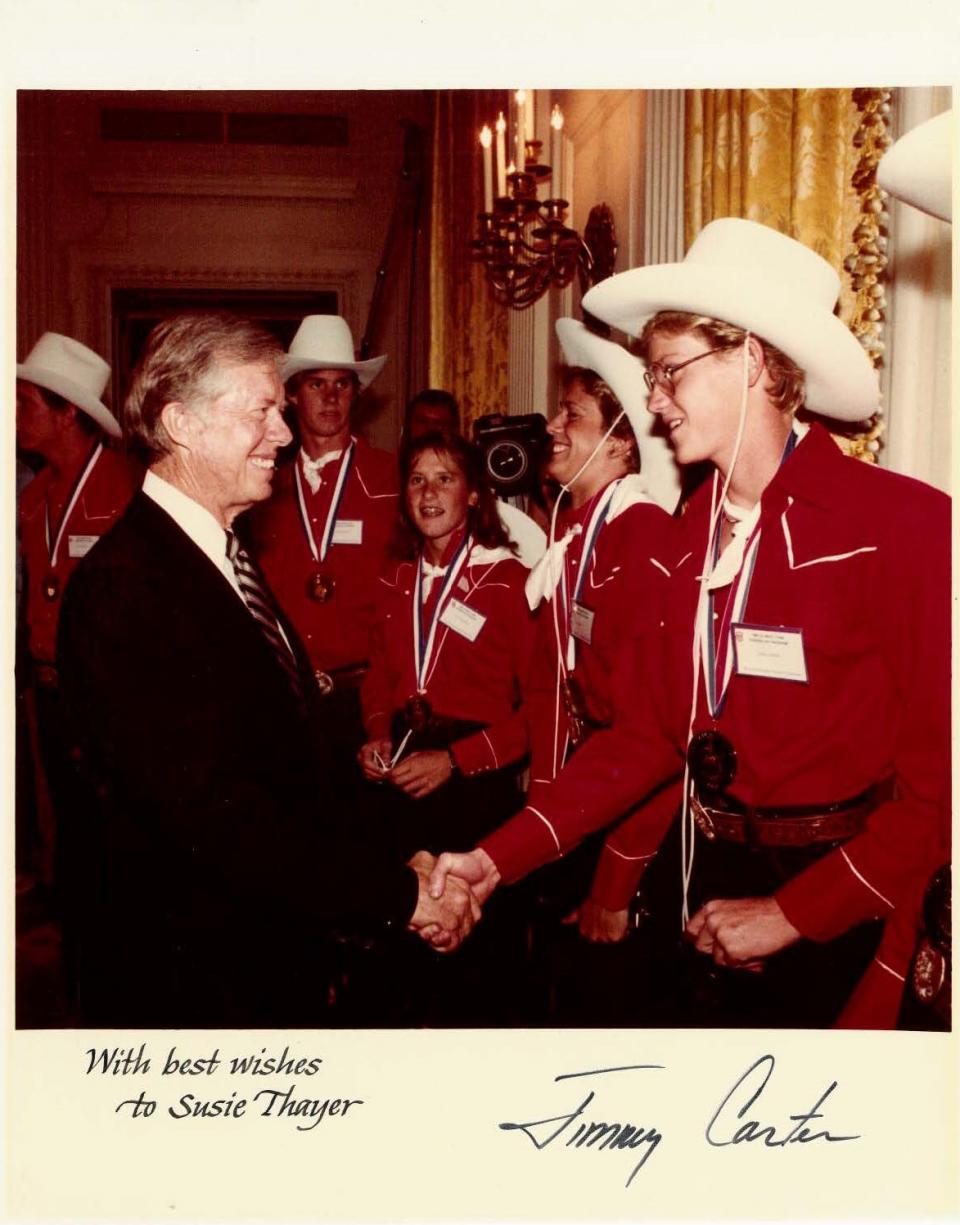

It was then, in the summer of ’84, that resentment started to boil. For years, Thayer couldn’t look at Jimmy Carter’s face. He’d lost reelection several months after the boycott, but would still pop up on the news. Whenever he did, Thayer seethed. She hated him. The mere thought of the man sent her spiraling toward a painful place.

And then a funny thing happened: Thayer returned home, engrossed herself in the family irrigation business, never said a word about swimming ... and forgot. About Carter. About the Olympics. About everything.

Any thought of the sport she’d dedicated her adolescence to came accompanied by indignity. Rather than cope with it, rather than reframe memories, she suppressed them. She’d meet with clients, build relationships with colleagues. None of them knew she’d ever been an elite athlete – and as she pressed on in life, still confused by her identity but successful in her career, it was as if she hadn’t been.

*****

Jesse Vassallo returned to Puerto Rico in 1985. Back to Ponce, where he latched on with his family’s manufacturing company. In 1987, he had his first kid, a boy. In 1988, he started his own business, producing solid-surface materials for the construction industry. He rarely thought about sports.

Dozens of his 1980 teammates felt similarly in the aftermath of the boycott. What once had been their everything became a source of utter emptiness in their lives. Many distanced themselves from the Olympic world and the public eye throughout the ’80s. Some disappeared for good.

But in the ’90s, Vassallo’s first-born turned 3, then 4, then 5. The pool tempted Jesse. He’d been for a few recreational swims. One day, he took his son to Club Deportivo, where all those years earlier he’d acclimated to the water. Now, he jumped in with the boy and taught him the basics.

Gradually, the father-son lessons became community sessions. One pupil became two, then three, then five. And the pool became what it had been for Jesse’s father two decades earlier, a local gathering place, and a creator of bonds.

Vassallo hardly fancied himself as a coach, and certainly not an elite one. He realized, in the process of teaching kids, what swimming had taught him. He realized he loved the look on their faces when they overcame obstacles. After dabbling in politics, he moved back to South Florida. Today, he schools an entire team of teens – but not to build swimmers capable of winning the Olympic medal he never did. He coaches to build swimmers who’ll dive into a pool, perhaps finish fourth sometimes, get up the next day and go again.

*****

Susie Thayer’s memories resurfaced and tormented her. Years of suppression were broken by the occasional businessman or family friend. Strangers would hear she was an Olympian. What was that like? they’d ask. How’d you do?

What was a point of pride for so many instead stirred anger. And shame. Many 1980-only Olympians have struggled with that so-called “second question,” the Did you medal? or How’d you do? Some have developed strategies for dealing with it. Others haven’t. Thayer certainly hadn't in the mid-2000s. The question provoked thoughts of Carter, of the boycott, of fury.

All the while, she still felt like a man in a woman’s body. She’d lived four decades in it, but the conflict was wreaking havoc in her head. She began seeing a therapist once a week, sorting through anger and confusion. In 2011, she transitioned publicly to Sam.

Sam Thayer had also been reading. Reading the bible, and reading books about forgiveness. He read tales about the Holocaust. He listened to NPR, and heard a segment with a woman whose sister had been killed in a concentration camp. But the woman no longer harbored ill will. Thayer studied her story of pardon, and thought: Enough. I really gotta do the same.

Through therapy and inventory and journaling, he learned to forgive. He heard of Carter’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning humanitarian work, and said to himself: “Good lord, I gotta let this go. This man is a damn saint.” So on Sept. 20, 2015, he sat down and wrote. “Dear Former President Carter,” he began. “Forgiveness and letting go of struggle is a rewarding experience. I believe the miracle of setting ourselves free of those chains that cause so much personal pain truly sets our souls free.

“Thank you for that experience.”

He did not, however, tell Carter he agreed with the boycott. In fact, two years earlier he’d attended a transgender conference in Atlanta. The Winter Olympics in Sochi were five months away. A speaker began condemning Russia’s anti-LGBTQ laws, and advocated for a boycott of the Games. Sam stood up.

His body quivered as he spoke. “I’m transgender, I understand where you’re coming from,” he told a room of hundreds. “But I also was on the ’80 Olympic team. And this is the worst thing you could ever do to an athlete or young person. Please, consider changing your thought process.”

And if other members of the ’80 team had been at the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Atlanta that day, if they’d seen Sam rise impulsively and speak from the heart, they’d have nodded their heads vigorously.

Please, they’d have echoed. Never again.

*****

That’s the other common message that came out of 80-plus hours of interviews. It’s the other reason many want this story told. Some wonder why this happened to them. Perhaps, a few muse, so that it won’t happen again. With U.S. politicians considering retaliatory action against China for its handling of the coronavirus, calls for a boycott of Beijing 2022 have begun. An army of 1980 Olympians stands at the ready if those calls ever crescendo. Anita DeFrantz, now an IOC VP, would be one of its generals. Willie Banks, a 1980 triple-jumper, would be another. “I will fight like crazy,” he says.

And the IOC’s current president would lead them into battle. Thomas Bach was a West German fencer and gold medal hopeful in 1980. The boycott ended one career but launched another. “After we lost this fight,” Bach says, “I decided to come into sports administration to make sure future generations of athletes would not have to suffer from such a senseless boycott again.”

Whether it was “senseless,” or whether it “worked,” are subjects of great debate. Many athletes write it off as futile. Some historians agree. Others argue there’s no way to know. The Soviet-Afghan war lasted nine-plus years. The boycott’s true purpose was to punish the Soviets and deprive them of a legitimizing international festival, the value of which is unquantifiable – because it never happened in full force.

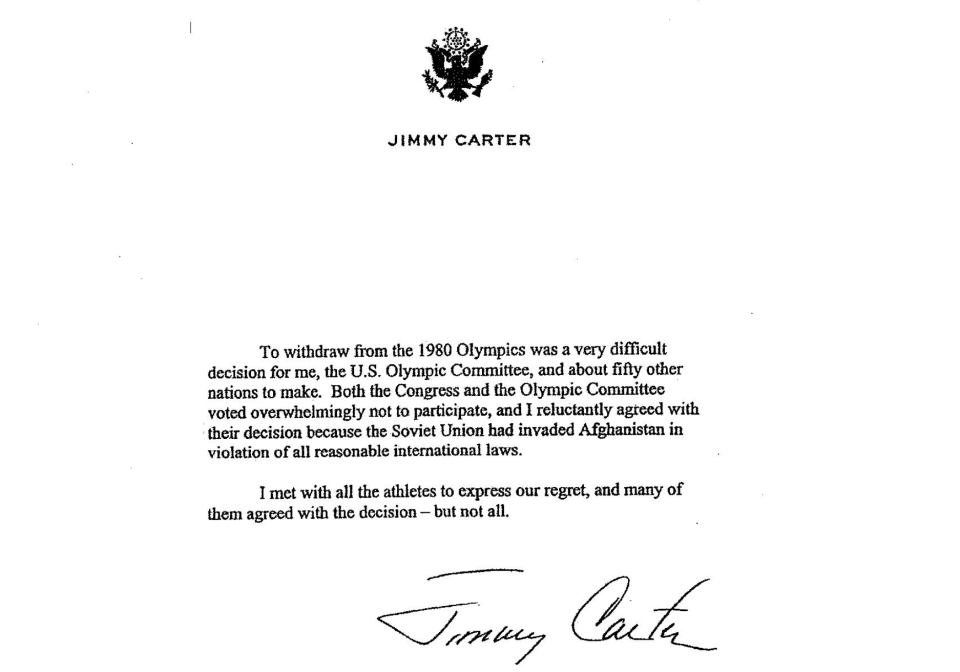

Berenson, the White House staffer involved in the boycott effort, says it “absolutely” was the right decision – just “not executed very well.” And Carter? He admitted in his memoir that he “had no idea at the time how difficult it would be for me to implement it or to convince other nations to join us.” He has not publicly said he regrets the decision. His spokeswoman declined to comment.

Carter did, however, respond to a group of middle-schoolers in 2011. They had delved into a big history project on the subject, and written to Carter for his retrospective thoughts. “Both Congress and the Olympic Committee voted overwhelmingly not to participate, and I reluctantly agreed with their decision,” he told the kids in a signed note. “I met with all the athletes to express our regret, and many of them agreed with the decision – but not all.”

The “attempt to rewrite history” rankled a few 1980 Olympians who saw the letter. “You SOB,” rower Carol Brown thought. The vast majority of the team, of course, did not agree with the decision, and still don’t. Several have crossed paths with Carter in the years since. The interactions they describe are awkward at best.

Some athletes crave an apology, but most realize: What would that achieve? Some found honor in sacrifice, and cherish the Congressional Gold Medals they were awarded that summer. Others clarify: “We didn’t sacrifice. We were sacrificed. There’s a difference.”

What they want is more recognition – recognition that they were, and are, Olympians.

*****

Tracy Stockwell, née Caulkins, lives happily in Australia now. Once every few years, she finds her way back to the States. Last decade, she took her daughter to visit colleges on the West Coast. At Stanford, they sat down for a lovely lunch with three of Tracy’s 1980 teammates. They reminisced about travels and teenage fun. They chatted about marriages and children and their lives.

In the car afterward, Tracy’s daughter asked: “So mum, you all swam together?”

“Yeah,” she said.

“Did they go to the Olympics?”

Tracy paused.

They were all Olympians, she knew. But … “No.”

They were, are, what some call “Ghost Olympians,” or “the forgotten team,” or “the team with no result.” The USOC says they’re Olympians. The IOC says they aren’t. Asterisks and “(Boycott)” accompany their names. Says Craig Beardsley, swimmer and would-have-been gold-medalist in 1980: “We don’t really know who we are.”

“This was an Olympic team,” says Mike Moran, the USOC spokesman at the time. “And it was simply erased as if it didn’t exist.”

Sport-by-sport, they have had official and unofficial reunions, but never as a full group. Some athletes say the shared suffering strengthened lifetime bonds. Others have fallen out of touch. Some take pride in being an Olympian. Others hide from their athletic pasts. Some, like Beardsley, have returned to sports to make the world a better place. Some learned to ignore what they can’t control and focus on what they can. Others still harbor bitterness.

Some, like NBC swimming commentator Rowdy Gaines, have parlayed sporting success into careers. Nancy Hogshead-Makar fights full-time for female athlete empowerment. Sue Walsh has spent three decades in the athletic department at her alma mater, UNC. Every once in a while, she speaks to groups of young swimmers, and tells them about the boycott; about overcoming heartbreak; that “the lessons you learn in disappointment [can be] more valuable than the lessons you learn from success."

Others still struggle. Some have faded from view. Others have seen their lives go seriously astray.

A couple months ago, meanwhile, Jesse Vassallo was preparing the Pompano Beach Piranhas, his youth swim team, for their championship meet on Friday, March 13.

On Thursday, March 12, the world screeched to a halt.

*****

Vassallo had never told his young swimmers about the boycott. That changed when COVID-19 upended their lives. Twenty-four hours before the meet of their dreams was set to begin, organizers called it off. Jesse convened the kids. He had a story to tell.

A pandemic and a boycott, of course, are two very different things. “This is about everybody, and it’s real,” Vassallo notes. “The other one was manmade.” This is about saving lives. Nobody could promise the other one would.

And yet what athletes are enduring is remarkably similar. “I know the feeling, intimately, of having something pulled out from under you,” Hogshead-Makar says. Several 1980 Olympians have been asked to speak to college and youth sports teams about their experiences. Edwin Moses, a member of that '80 team, organized a virtual town hall to connect Olympians of 40 years ago with today's. The USOC has been working to forge similar mentorships.

Vassallo, weeks before the cancellations, had spoken to his swimmers about “resilience,” and that’s the message he reiterates now. “You train, train, train, and not everything comes like you want it to,” he tells the kids. “And things get in your way. You break an ankle, or you get sick the day before a meet, or you false-start.

“But you don’t give up,” he says. The water still waits for you. The wall remains there for you to touch. It’s a lesson he learned from the boycott, and now applies to life. As his Piranhas wrestle with uncertainty, it’s a lesson he hopes to pass on.

Jesse himself has been struggling too. His bank account is running perilously dry. He doesn’t see pools reopening anytime soon. He worries about what life will look like by the time they do.

But then he sets up his computer and positions the camera. He joins a daily Zoom call with his homebound swimmers. For an hour, he puts them through a punishing workout. Situps, pushups, squats. Their arms tremble. Their legs quake.

Each day, he half-expects them to blow off tomorrow.

Each day, they set aside inconveniences; they swallow frustrations and disappointments; and they come back for more.

————————

Jay Busbee and Jeff Eisenberg contributed reporting.

Part 1: The saga of the 1980 boycott | Part 2: The lives forever changed

More: Robbed at the 1980 Olympics? | An American medals in Moscow | Muhammad Ali plays diplomat