Oller: Former Ohio State QB Craig Krenzel rues loss to UM, softening of football culture

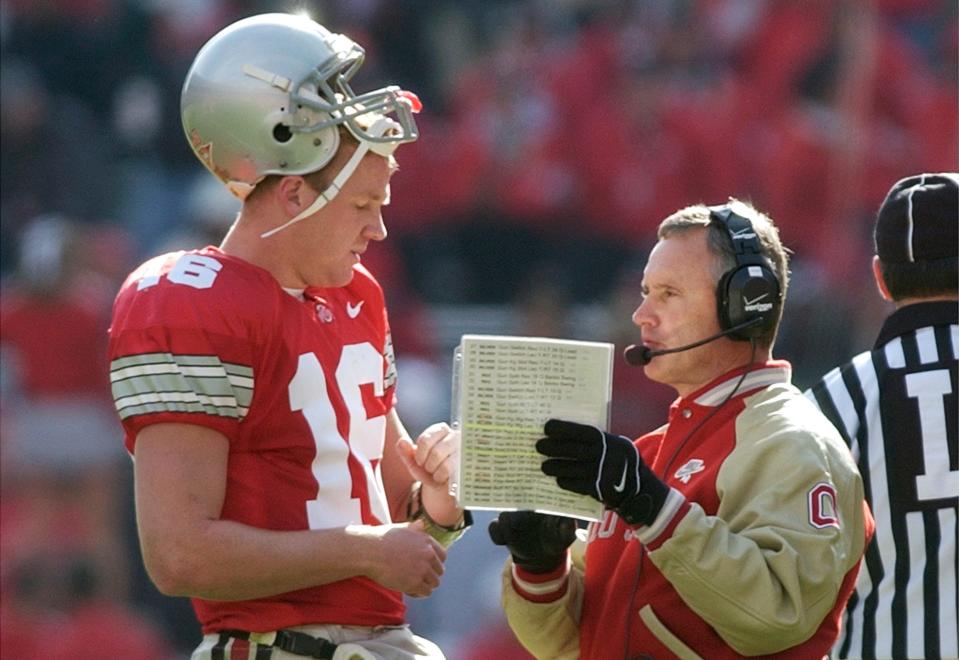

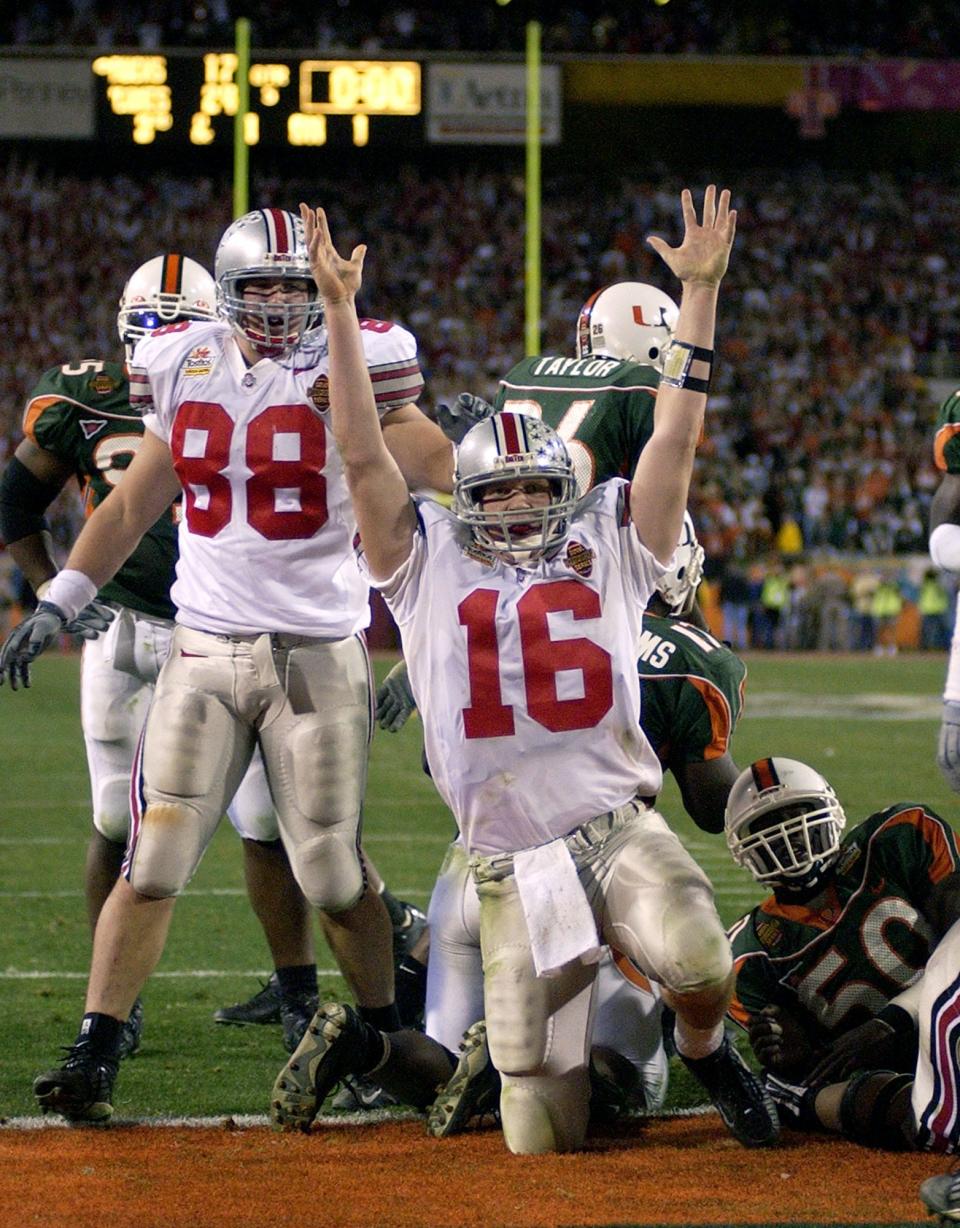

Craig Krenzel is 42. Hard to believe, especially for those of us who were about that age in 2002 when the Ohio State quarterback led the Buckeyes to the BCS national championship.

As he ripens, Krenzel knows he risks sounding like the “get off my lawn” guy by comparing today’s Buckeyes to the back-in-the-day bunch he played with two decades ago. He calls today’s OSU players “kids,” most of whom are not much older than his own children.

And a lot of those kids, he says, need talking to. They arrive on campus expecting, even demanding, to be treated like stars, having been convinced by family and friends they are God’s gift to football, with NIL money to prove it. And at the first sign of struggle they begin weighing their transfer portal options.

Krenzel strongly believes the newbies need competitive toughness – the “dawg” he calls it – trained into them.

“I don’t think it’s an Ohio State problem. It’s an Ohio State challenge,” he said during a nearly hour-long conversation that covered everything from OSU’s 30-24 loss at Michigan to Maurice Clarett’s hard hat work ethic during his one season on the field in 2002. But mostly the discussion centered on football culture, specifically what it takes for teams such as Ohio State to overcome adversity and win championships. The way those ’02 Buckeyes did.

The problem, as Krenzel sees it, is a societal mindset heavy on entitlement and light on accountability. The challenge for the Buckeyes is to break free from “soft” culture by passing down hard but necessary lessons from coaches to upperclassmen to incoming freshmen.

“I’m not there, so I don’t know for sure,” Krenzel said of what may be ailing OSU in their road blocks against Michigan.

But he sees things. Hints of trouble. And as a former player who wants the program to reach its potential, he is not afraid to point them out, both generally and in specifics.

“I wholeheartedly believe it’s a generation of kids that, when they step on campus the expectations of these athletes is a much different experience than 10 or 20 years ago,” Krenzel began. “I’m not saying that to sound like an old man. Frankly, I saw some of it with Reese (Maurice Clarett). If he had been managed differently by people in his corner, if family members had been saying, ‘You’re not there yet. You could be Archie (Griffin) but you’re not there yet.’

“His vision was so good … that instinct you can’t teach. We saw it a little bit, but he came in buying how good he was. We tried as a team to knock that down, and when it worked, on the field he was phenomenal. Off the field, when you start listening to how good you are, eventually people are going to be lying to you.”

Krenzel was emphatic. Clarett was all business during practice and games.

“Maurice Clarett was a dawg,” Krenzel said, describing the tailback’s mental and physical toughness. “He competed every day, knew his stuff and I never once questioned, not one time, when I dropped back did I think Reese was not going to do his assignment.”

Dawgs. Krenzel was one. He insists every team needs as many as it can get. He wonders if Ohio State has enough of them.

“Every kid comes in as a freshman, and they’re all puppies," he said. "They need to grow into dawgs. Older players need to whip the young pups into dawgs.”

The 2002 Buckeyes had dawgs everywhere.

“Donnie Nickey was an absolute savage,” Krenzel said. “Tim Anderson, Alex Stepanovich, Will Allen. Ben Hartsock. Cie Grant was a competitor. In his own way, Michael Jenkins was a dawg. These guys competed like no one was guaranteeing them the next play. Some of it is circumstantial. Our guys were fed up, coming off 6-6 (1999), 8-4 (2000) and 7-5 (2001) seasons, with back-to-back bowl losses to South Carolina. At some point guys have to get pissed off enough to say, ‘OK, we lost to Michigan three times.’ ”

Was that type of anger boiling over in the 2023 Buckeyes on Nov. 25? Krenzel can’t say for sure, but he knows it was not there last season, when during the second half Michigan tossed the Buckeyes around like rag dolls in rolling to a 45-23 win in Columbus.

“I was a little disappointed, as a former player, in our guys’ performance last year,” Krenzel said. “You want to talk dawg? That team had no dawg the second half. It was tough to watch.”

This season’s six-point loss in Ann Arbor was not as embarrassing, but after halftime the Wolverines still dominated at the point of attack.

“We did not play a great game,” Krenzel said. “We physically got pushed around a little bit.”

And not just at the line of scrimmage. Krenzel saw something in Ohio State’s opening drive that gave him pause. For all the praise heaped on wide receiver Marvin Harrison Jr., deservedly so, Krenzel insisted, the Heisman Trophy finalist failed to fight for the ball on a slant pattern that ended in disaster.

It pained the former quarterback to see Kyle McCord take most of the blame for the first-quarter interception that led to Michigan’s first score.

“When you’re a wide receiver and you run an in-breaking route, where you square in like that, you can’t ever let the corner beat you inside to the football,” Krenzel said. “If I throw that pass, as a quarterback the guy playing you on the corner is not in your thought process. When I watch that play, it looked like a (run-pass option) of sorts, and maybe one we don’t throw often on. Maybe Marvin was kind of taking the play off and, ‘Oh, Kyle threw it.’

“If that’s the case, and I could be 100% off base, then there is a huge culture problem. Every play is an opportunity to prove that when I put my name on something I do it with the best of my ability. That’s what I loved about Michael Jenkins. I know this, that Michael Jenkins never got undercut on a slant route. Ever. I look at that first pick and man, it feels like Kyle was as surprised as we were as fans. There was a degree of ‘Whoa, what just happened there?’ ”

It is tempting to blame coaches when players show lack of “competitive stamina,” as Ohio State staffers describe it. Ryan Day is paid $10.2 million to make sure his players go all-in on every down. But Krenzel takes a different tack, sympathizing with coaches because of the cultural shift taking place that, instead of players expecting to pay their dues, they expect to get paid to do.

“I think it would be extremely hard to coach the dawg into a group of guys,” he said. “When I was done playing, I thought about going into coaching but am so glad I didn’t. I don’t know how you handle today’s generation.”

Day has tried to model for his players an edgier attitude this season, perhaps determining the locker room leaders are more flatline than fiery. He went on a calculated rant against Lou Holtz after the Notre Dame game, angrily insisting the Buckeyes were “a tough team.” He also has been more animated on the sideline, though it also could be a sign of increased stress.

Regardless, Krenzel is more of the mind that self-motivation is more effective than relying on externals.

“The bottom line is who plays in the games,” Krenzel said. “You can have the most rah-rah, loudest barking coach, but if the players don’t authentically compete every play … it’s their reputation that is on the line.”

At the risk of promoting a narrative that may not be entirely true, it seems the Buckeyes are almost too nice for their own good. I do not recall a more pleasant, mannerly group of guys to interview. My question is do their “Thank-you’s” become “bleep you’s” on the field?

“Your personality has to be different between the white lines,” Krenzel said. “Guys I played with, off the field were good dudes. On the field they were nasty and relentless, and relentless competition is not something you see in society these days.”

If it’s on players to flip the switch from nice to nasty, should coaches be let off the hook for failing to set a proper competitive tone? Not at all. They can and should create an environment of accountability not by how loud they yell, but by targeting who they criticize.

“The best teams ride the stars the hardest,” Krenzel said. “A freshman comes in and sees (OSU strength coach) Mickey Marotti and (offensive coordinator/wide receivers coach) Brian Hartline go after Marvin. Knowing his status on the team, the freshman says, ‘If that is the status guy and the strength coach and head coach and offensive coordinator and position coach can relentlessly attack him, and the dude keeps responding?’ Marvin could make seven figures in the NFL, but he sticks around his junior year and gets beat up physically and emotionally and is tougher for it. Those young guys see that and buy in, and the ones who don’t buy in hit the portal. You don’t want them anyway.”

Don’t fit the culture to the elite player but the player to the elite culture.

“There are always going to be six to eight schools like Ohio State that also are getting their share of the best talent,” Krenzel said. “But you look year in and year out, and culture wins.”

How strong is Ohio State’s culture? I applaud the Buckeyes for showing love and respect for each other through “The Brotherhood.” I’m just not sure they have enough dawgs in the hunt.

Get more Ohio State football news by listening to our podcasts

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Ohio State football quarterback Craig Krenzel recalls 2002 Buckeyes