No, sports' TV ratings haven't been great since returning. Despite what President Trump and others say, it doesn't really matter

The return of live sports was supposed to usher in an explosion of interest. Americans were going to hunker down in front of their TVs and watch in record numbers because, well, there’s not much else to do during a pandemic and everyone has missed their favorite distraction.

But that didn’t quite happen. In fact, a cursory glance at TV ratings and headlines about viewership suggests the overall interest in sports may even be down.

The NBA’s ratings were already down a bit from last year, and they dipped again when sports started back up after the COVID-19 suspension. NASCAR started red-hot as one of first major American sports back on network television during the pandemic, but then dropped to below-average ratings. And MLS, which didn’t have high expectations to begin with, still managed to underperform.

Are people put off by the awkward lack of crowds? Are they too focused on the pandemic and the upcoming presidential election? Do they not consider bubble tournaments “real” competitions?

All those things may be true. But TV ratings don’t actually show that people have suddenly become less interested in sports.

A closer look shows that viewing habits are changing during the pandemic, but sports are as popular as ever. And as much as conservative pundits and even President Donald Trump have tried to turn the NBA into their latest political wedge, the NBA has little reason to worry.

“You can find the leagues or the types of content that may be underperforming but, on the whole, sports viewership is doing pretty well,” says Daniel Cohen, senior vice president of Octagon media rights consulting. “Everything out the gate has been taking off like a pent-up bottle rocket — some have been able to maintain it or grow, and others have regressed.”

Why have sports TV ratings looked bad?

On paper, there have certainly been some winners and losers of sports on TV during the pandemic.

On the winning side, the recent PGA Championship delivered its highest cable ratings in a decade for ESPN, and on CBS it saw an increase over last year’s competition. The WNBA had its highest regular-season audience in eight years for Wings-Mercury last weekend.

But other sports — bigger, more important sports — haven’t been similar success stories.

MLB has been a mixed bag at best. The league’s opening day was huge, drawing 4 million viewers — the most for a regular-season game in nearly a decade — but nationally ratings quickly fell. At the same time, regional sports networks have seen triple-digit increases in MLB games.

The NBA has been down, and not even the start of the playoffs has changed the narrative. Tuesday’s thrilling Blazers-Lakers game delivered 3.5 million viewers, the NBA’s largest audience since the league restarted last month, but midday games performed poorly and the start of the playoffs is down 34 percent from last year.

“For the NBA, oversaturation is a huge part of it,” says Jon Lewis, who runs Sports Media Watch. “You have tons of these games every day, doubleheaders, tripleheaders, games on at all hours of the day. It’s hard to build an audience when you have a ton of games that are not particularly meaningful.”

To use ratings to determine if people are watching sports, it’s important to understand what TV ratings actually measure.

Contrary to what people assume, they are not just the number of people who watched something on TV. Instead, TV ratings are a calculated average derived from the number who watched and how long they watched for.

In other words, if an NBA game reached the same number of people, but everyone watched a few minutes less because there is also baseball, hockey and soccer on TV, the NBA’s ratings will go down.

Patrick Crakes, a former Fox Sports executive who now does media rights consulting, says that total consumption of sports is actually up during the pandemic between 100 percent and 150 percent, something individual ratings won’t show.

“Total consumption can be up and the ratings still be flat,” Crakes says. “If you put a lot of sports out there, people are going to watch individual things a little bit less. More people are watching television, but they are spreading out their viewing in more places.”

“Context matters,” he adds. “If the idea is that sports media is struggling, that’s clearly not true.”

In some ways, the narrative about sports struggling on TV has been dictated by expectations.

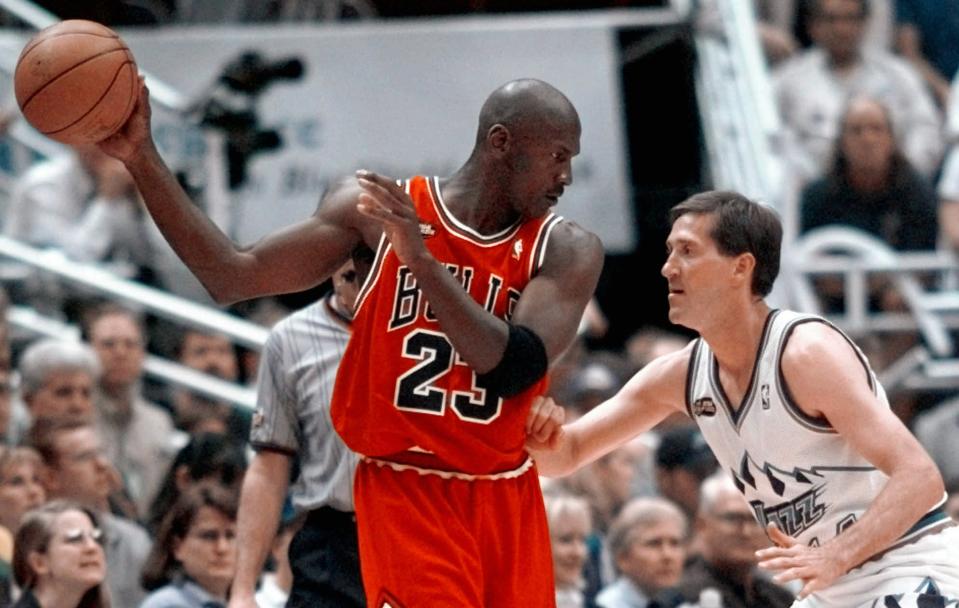

When the Michael Jordan documentary “The Last Dance” drew record ratings for ESPN, conventional wisdom became that there was a massive, unprecedented demand for sports — an assumption that hasn’t borne out.

The National Women’s Soccer League was the first U.S. team sports league to return with relatively low TV expectations, and earned its highest ratings in league history by a wide margin. But their male counterparts at Major League Soccer struggled, and an experiment of 9 a.m. ET morning games ended in failure, unable to crack 175,000 viewers per game. That’s despite MLS having a two-week jump on the NBA, MLB and NHL.

“The excitement over 9 a.m. MLS games was something that can only exist if you thought the appetite for sports was dramatically higher than it actually was,” Lewis says. “These are decisions that, I think, were influenced by the perception [that] sports were going to have a huge increase in ratings.”

Sports caught in the political fray

To some extent, the digs at the NBA’s ratings, in particular, have been driven by conservative pundits, who have manufactured a feud with the league, and even President Donald Trump, who has spent his time in the middle of a deadly pandemic tweeting about basketball TV ratings.

The narrative that Trump and others promote is that the NBA is losing viewers as players engage in social justice causes and use their platform for activism. To make their point, they compare the NBA’s lower ratings to those of right-wing outlet Fox News. But there’s actually nothing new about Fox News beating the NBA in ratings.

“People have an idea of sports being bigger than they actually are,” Lewis says. “There’s always this level of surprise that Sean Hannity beat an NBA game. Well, that happens all the time, going back years and years. It’s not about the number of viewers who watch sports. It’s about the demographic.”

Indeed, TV ratings are not a measure of how popular or culturally relevant something is. TV ratings are used to sell advertisements.

For advertisers, the 18-34 age bracket is coveted as the most valuable because those are the young consumers companies want to reach before lifelong brand loyalty develops. In that demographic, NBA games do way better than any show on Fox News, as Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban recently pointed out.

The big-picture viewership trend for the NBA looks pretty normal, even with the schedule congestion that has flattened average TV ratings. The notion that player protests could be hurting the ratings just isn’t supported by the numbers.

“Nobody is really going to stop watching a game, I don’t think, because the first minute shows people kneeling,” Crakes says. “A lot of people won’t see it anyway. Even with the politicization of sports, I still don’t think it’s enough to lose that escapism.”

Crakes, who played a senior role in Fox Sports’ programming strategy for two decades, says the fact that the NBA is holding onto its audience, even if the ratings are slightly down on paper, is an indisputable positive.

“If the viewing environment was normal and ratings were down after sport had been gone, we might be able to draw conclusions at the end of the season,” Crakes says. “But because that’s not what we have, it’s hard to spin it as negative.”

For sports as a whole, however, being caught in political crossfire is unavoidable, whether players stage protests or not.

As the election gets closer and voters have to choose between Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, they will probably watch less sports and more news. Perhaps the effect will be even more acute amid a pandemic that has disrupted everyone’s lives and an election that may have a direct effect on the pandemic.

That would match past precedent. In 2016, the NFL — the undisputed ratings juggernaut — saw a dip in its ratings as more people focused on the upcoming election. In 2001, in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the NFL’s ratings were comparatively modest then, too.

“We know that in election years, ratings tend to go down,” Lewis says. “When you have so many things going on in the country and then all of these different sports going on at the same time, there’s only so much television any person can watch in one night.”

The ratings just don’t matter as much as having games to put on TV in the first place. Even though the early morning MLS time slot performed poorly, the league chipped away at its contractual obligations to ESPN, and ESPN did the same for cable providers and distributors.

That’s why ESPN and parent company Disney hosted the NBA and MLS tournaments, letting teams stay at Disney World resorts and competing at the ESPN Wide World Of Sports Complex. Networks and leagues are in it together, and they both avoid financial losses by having games on TV.

But the loss of college football could be a concern.

Crakes estimates that without the Big Ten and Pac-12, Fox lost as much as 80 percent of its college football inventory. That should only be temporary; for now, the working assumption is that the pandemic will affect sports into 2021 but not long-term. However, if the disruption lasts any longer and games can’t be played, then it’s time to worry.

“As long as you’re on the air, period, you’re winning,” Lewis says.

Caitlin Murray is a contributor to Yahoo Sports and her book about the U.S. women’s national team, The National Team: The Inside Story of the Women Who Changed Soccer, is out now. Follow her on Twitter @caitlinmurr.

More from Yahoo Sports: