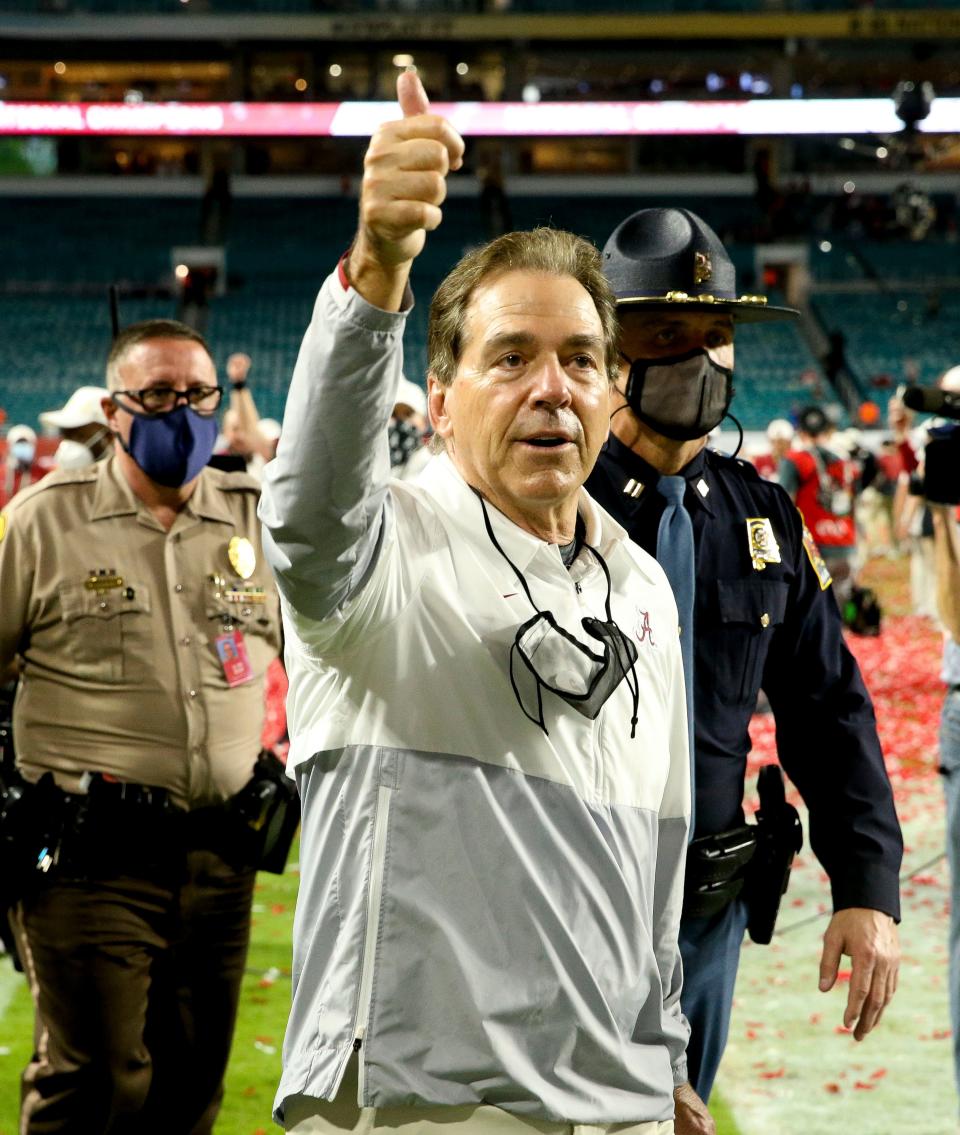

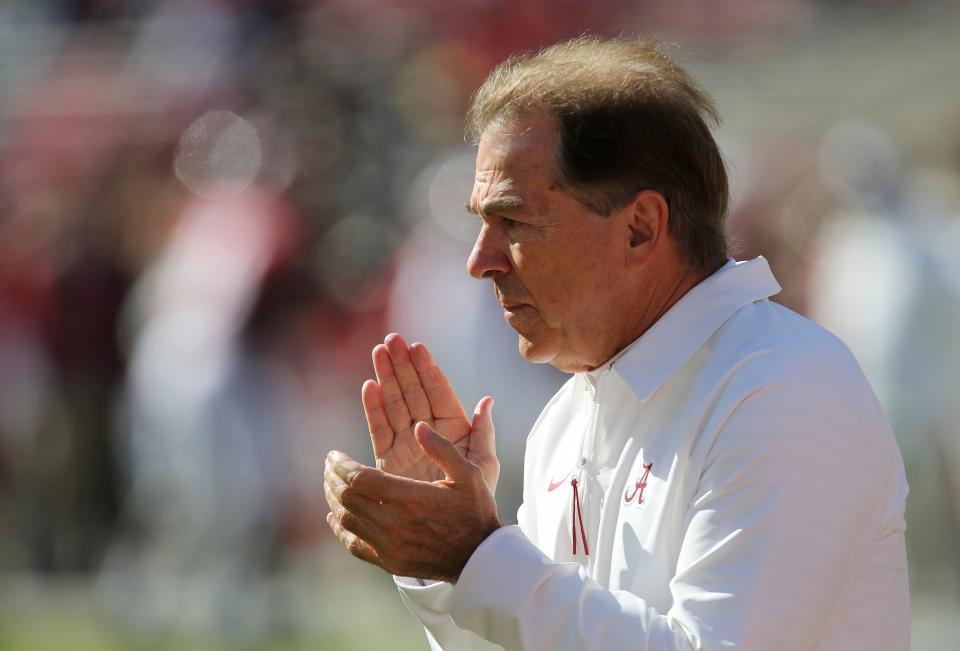

How Nick Saban transformed Alabama football — and changed a blueblood forever

This story appears in the new book from The Tuscaloosa News, "Nick Saban: 15 Epic Seasons That Changed Alabama Football Forever." The limited-edition 160-page book, which tells the story of Saban's life, meteoric coaching rise and includes a foreword from Paul Finebaum, can be purchased for $39.95 at SabanBook.com.

Eli Gold walked into Nick Saban’s office needing to record the video.

Gold, the radio voice of Alabama football, once again was set to serve as emcee for Bama Blast, a pep rally for freshmen at Bryant-Denny Stadium. Coaches for other UA programs showed up with a couple players to speak to incoming students, but the Crimson Tide’s football coach had traditionally only recorded a video that played on the stadium’s big screen.

“When do you want to record this thing?” asked Gold, who will miss the start of the 2022 season due to health issues.

Saban looked puzzled.

“Why would I want to record it?” Saban replied.

“Well, that’s the way it’s always been done,” Gold said.

Then Gold learned a lesson he hasn’t forgotten in Saban’s 15 seasons in Tuscaloosa: You don’t use that phrase – the way it’s always been done.

One for the home (games)?: Alabama football takes step for alcohol sales at Bryant-Denny Stadium, applies for liquor license

Preseason ranking: Alabama football takes reputational national title in USA Today preseason poll | Goodbread

Saban told Gold he intended to attend in person but needed to know the time.

“3 p.m.,” Gold said.

“I will be there at 3:01,” Saban replied.

On the day of the event, freshmen were filing in. No sign of Saban at 2:59 p.m. Gold decided to start the program.

Then at 3:01, Saban walked out of the tunnel. Gold handed him the mic and off he went. The new football coach shared how everyone was part of this project. Even someone who couldn’t run, throw or catch the football, Saban reasoned, could still contribute.

“He had everybody eating out of the palm of his hand,” Gold said.

Saban proved then, and time and time again over his 15 seasons in Tuscaloosa – winning six national championships and eight SEC titles in one of the most dominant stretches in college football history – that he is not afraid of change when growth and success are the byproduct.

“You contrast that 2009 championship team with 2020 or the 2017 season with the win over Georgia in Mercedes-Benz Stadium on the Tua (Tagovailoa) throw, it’s almost like two different programs,” said Phil Savage, who was Alabama’s radio color analyst from 2009-17. “They’re just dressed in the same uniform. I don’t know that a lot of people could do that. I think that’s what puts him on the Mount Rushmore of college football coaches.”

Pee on the carpet

Change was an immediate and colossal part of Saban’s start in Tuscaloosa in 2007 after leaving the NFL’s Miami Dolphins to return to the college game. The culture in place at Alabama, under his predecessor Mike Shula, did not meet his standard.

And where there is change, there can be resistance among players from the previous regime.

“You’ve got a dog, you've had a dog for a couple of years and you've allowed that dog to pee on the carpet,” said Todd Alles, Saban’s first director of football operations at UA. “And now all of a sudden he's not allowed to pee on the carpet. The dog’s a little confused now, and the dog doesn’t understand. ‘Wait a minute. I've been allowed to pee on a carpet for two years. Now all of a sudden I'm getting my (butt) beat with a wadded-up piece of paper for peeing on the carpet.’ Eventually, he quits peeing on the carpet. That’s I guess an analogy that I can come up with that might have been the mindset of the players for this new way of doing things.”

Saban installed a culture of accountability, and it took on many forms.

“He held everybody accountable for off-the-field stuff as well as on the field,” linebacker Eryk Anders said. “He always had the saying, ‘How you do one thing is how you do everything.’”

One example was in how Alabama handled drug testing. Anders said Saban put clear measures into place that if a player failed a drug test, he knew the punishment. If he failed two, the penalty was also clear. Previously, Anders said, players weren’t held accountable like that.

“The consequences were real with Saban,” Anders said. “Saban followed through with all the stuff he said he was going to do.”

During winter conditioning, Saban also sent a message to players that whatever work a player does, it must be done correctly, no matter how many times it takes. That showed through in what Alles called, “Perfect 100s.”

Alabama players would line up in groups of eight to 10 to run 100 yards. None could make a mistake. Each had to have his hand on the line. They couldn’t leave early but also not late. Everybody had to sprint through on the other end. Once they did it, they turned around and came back.

“We might end up running 25 100s until we got 10 perfect,” Alles said.

Saban demanded nothing less from his new team as he strived to make his players’ standard as high as his own.

Coach and community leader

Judy Holland made the obvious choice in Alabama’s gubernatorial race one year: She wrote in a vote for Saban, even though he wasn’t on the ballot.

Holland considers herself one of Nick and Terry Saban’s biggest fans. Football has little to do with it.

“He’s way more than a football coach here,” Holland said.

Holland is managing director of High Socks for Hope, running the volunteer organization’s relief and humanitarian service. The Sabans have often aided those efforts in Alabama and surrounding states. The organization grew out of the 2011 EF4 tornado that devastated Tuscaloosa.

It was during that time of loss and destruction that Saban’s influence in the community was intimately felt.

Saban would arrive at relief centers unannounced to show gratitude to volunteers. He spoke with search-and-rescue teams. And in the aftermath, the Sabans funded 13 homes for victims displaced by the storm, one for each of the 13 national championships won by Alabama at the time. With each championship won thereafter – bringing the total to 18 entering 2022 – the Sabans have continued to build homes.

Prior to arriving in Tuscaloosa, the Sabans had never spent more than five years at any coaching stop. But by 2022, their roots had firmly been planted in Alabama. Both through football and initiatives such as the Saban Center, the state-of-the-art learning center for children along the Black Warrior River.

“The connection that Nick and (his wife) Terry showed to that community financially and emotionally,” Savage said, “I thought that really for the first time (in 2011), it really glued them to the fabric of Tuscaloosa and the state of Alabama.”

New age of defense

The construction of Saban’s early Alabama defenses wasn’t going to work long-term, thanks to the advent of hurry-up, no-huddle offenses. Gus Malzahn’s Auburn Tigers, Hugh Freeze’s Ole Miss Rebels and a Texas A&M team quarterbacked by Johnny Manziel – the 6-foot superstar with a tantalizing ability to wiggle out of trouble – provided the impetus for change, as each took down Alabama.

“They all, at different times, put a dent in Alabama,” Savage said. “The reaction was, ‘Wait a minute, we can’t just stay in this 3-4 defense and just dominate people with personnel. We’ve got to adapt and adjust to what’s going on around us and in front of us.”

So, Alabama adapted.

Personnel is the easiest way to spot the adaptations. The Crimson Tide had to recruit a new type of defensive player. No longer did Alabama seek to load up on players like Terrence Cody or Rolando McClain. Both were valuable pieces in those early defenses, but they didn’t have the right combination of size and speed needed to keep up with the new-age offenses.

Cody was a colossal nose tackle at 6-foot-5, 365 pounds. McClain was on the bigger side for a linebacker at 6-4 and 258.

Savage, who became a senior football advisor for the New York Jets after leaving Alabama, witnessed the shift. He watched the Crimson Tide begin prioritizing defensive linemen with greater mobility to impact the pass rush; and smaller, speedier linebackers who could not only make more tackles in space, but also negate more plays in coverage.

Christian Harris is a prime example. A 2021 draft prospect after starting for the Crimson Tide at inside linebacker for three years, Harris was a 6-2, 226-pound menace. He ran a 4.4-second 40-yard dash at the NFL Scouting Combine and had experience at defensive back in high school before Alabama turned him into a linebacker.

“I think they’re still trying to work through that and improve on it,” Savage said of Saban’s adjusted defensive style. “It’s just hard to play defense in college football.”

The evolution of offense

Ross Pierschbacher, a Crimson Tide offensive lineman from 2014-18, always watched for defenders to put their hands on their head or hips.

“If we look across the ball and we see guys with hands on their hips,” he said, “then we had them right where we wanted them.”

Players passed that along to the coaching staff. Let’s put it on them and go fast, the players suggested. Running the offense quickly and without a huddle made it difficult for defenses to substitute.

“I think that style of offense really changed the game,” Pierschbacher said. “You get those big defensive linemen in the SEC, and they’re not built for it. So we pride ourselves on wearing those guys down by going fast.”

For Alabama to keep up with the Joneses, it couldn’t just change defensively. The Crimson Tide needed to score more points.

So Saban adapted again. It began with the addition of Lane Kiffin, the former Tennessee and Southern Cal coach, as offensive coordinator in 2014. Kiffin brought a forward-thinking spread attack that stressed defenses, and each coordinator who succeeded him in the job – Mike Locksley, Brian Daboll, Steve Sarkisian and Bill O’Brien among them – added new thoughts, wrinkles and concepts that changed the identity of the Crimson Tide attack.

Alabama went from a run-first offense predicated on dominating up front and imposing its will with a methodical pace to one that’s built on quick-strike, up-tempo and run-pass option concepts.

“I think Bama realized, ‘Hey this is tough to play defense … so let’s join ‘em,’” Savage said. “And they have. You combine that with the elite athletes they’re able to recruit, and they’re a handful to handle from a defensive standpoint.”

Gunslingers

No position changed more than quarterback during Saban’s 15 seasons.

The Crimson Tide won its first championship under Saban with Greg McElroy under center. McElroy fit the mold of a game manager, though he did a bit more than that in leading UA to the 2009 title. Still, his main job was taking care of the football to let the running game lead the way while the defense dominated.

That’s no longer the case in Tuscaloosa.

“Now, you’ve got gunslingers,” Pierschbacher said.

In 2021, the Crimson Tide produced its first Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback in Bryce Young, whose 4,872 yards and 47 touchdowns as a sophomore set program records. Young was the No. 1 dual-threat quarterback recruit coming out of high school, according to 247Sports.

“That would have been unheard of 10, 12 or 15 years ago,” Savage said. “Now, nobody thinks twice about the fact that Bryce Young rolls in there and becomes a Heisman candidate as a sophomore and sets all sorts of records.”

In 2017, the Crimson Tide signed another No. 1 dual-threat quarterback recruit in Tua Tagovailoa, and UA added another five-star quarterback in Ty Simpson in the 2022 class. The outlier in the group, at least in terms of recruiting profile, is Mac Jones, a former three-star prospect whose development accelerated in the Alabama offense in 2020. Alabama’s run to the national championship that season made Jones a Heisman finalist and a first-round pick of the New England Patriots.

“The game has become quarterback-friendly,” said Burton Burns, an offensive assistant under Saban for more than a decade. “The game is score as many points as you can. In order to do that, you’re going to have to have an effective quarterback. Nick has masterfully understood that and made sure the priority was changed to have an effective quarterback moving forward.”

New rules, new methods

College football won’t stop changing, and Saban’s 15th season in Tuscaloosa was no different.

The advent of the transfer portal and NIL (allowing players to strike deals for use of their name, image and likeness) reshaped the landscape once again.

Saban took the change in stride.

Rather than stick to traditional ways of building a roster, primarily through signing high school recruits, Alabama added veterans like Ohio State receiver Jameson Williams and Tennessee linebacker Henry To’oTo’o. Both made quick impacts on a team that reached the national championship game.

Entering 2022, Saban struck again in the transfer portal. Needing help at cornerback, running back and receiver to offset the latest wave of NFL draft departures, the coach added three top transfers in LSU cornerback Eli Ricks, Georgia Tech running back Jahmyr Gibbs and Georgia receiver Jermaine Burton.

“My take on it is, (Burton) wanted to play with the best quarterback in college football,” Pierschbacher said. “Who wouldn't? You know, he's going to get him the ball and make him a first-round draft pick.”

Saban’s willingness to change has underscored the rise of one college football’s greatest dynasties. It is why UA remains the preeminent destination for the game’s top talent. Rather than settle into his ways, Saban has adapted and thrived.

“A lot of coaches don't have the guts to do to do that,” Gold said. “But meanwhile, here he is, with all of these national titles.”

Nick Kelly covers Alabama football and men's basketball for The Tuscaloosa News, part of the USA TODAY Network. Reach him at nkelly@gannett.com or follow him on Twitter: @_NickKelly

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: How Nick Saban transformed Alabama — and changed a culture forever