Why DFA is the WTF of baseball and how one player fought back

GOODYEAR, Ariz. – Eighteen days before Christmas, the package arrived. Inside of it was $600, maybe $700 worth of Seattle Mariners gear Danielle Shaffer ordered a few weeks earlier. Her husband, Richie Shaffer, had been traded to the Mariners by the Tampa Bay Rays in mid-November, and they figured there could be no better gifts for their parents and grandparents and siblings and cousins than some swag to show pride in their new baseball family. They opened the box, examined the clothing, remarked to each other how cool this was.

“Thirty minutes later, I got the call,” Shaffer said. “I was DFA’d.”

DFA is baseball’s acronymic equivalent of WTF. It means designated for assignment, which is the sport’s doublespeak for being removed from a team’s 40-man roster and being put on waivers for 29 other teams to claim. A spot on the 40-man is a treasure, and not only does getting DFA’d rob a player of that, it can incite a chain reaction that highlights the inanity of baseball roster management.

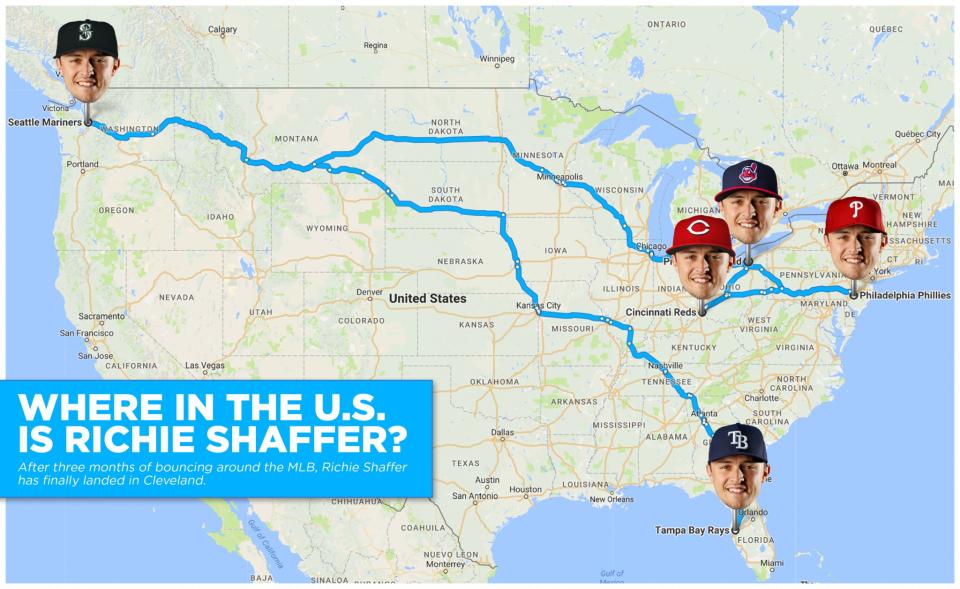

Over the course of 2½ months this winter, Shaffer’s rights belonged to five teams: the Rays, the Mariners, the Philadelphia Phillies, the Cincinnati Reds and the Cleveland Indians. After growing up in Charlotte the star of his youth-league teams, going to Clemson and helping lead the Tigers to the College World Series, going 25th overall in the 2012 draft to Tampa Bay and slugging all the way through the minor leagues, the kid who’d never been cut from anything was DFA’d four times in six weeks, told again and again, tacitly, that he wasn’t good enough.

[Sign up for Yahoo Fantasy Baseball: Get in the game and join a league today]

“That was the first time I’d ever been talked about in that light – as a player a team would consider DFA’ing,” Shaffer said. “A year prior to that, I was in the Futures Game. I know it’s a number’s game, but that was a weird sensation. A team was pretty much telling me it was willing to give me away for nothing. It was an ego hit.

“Baseball’s an odd business. The game is pretty simple, but the business is strange. Once you get DFA’d once, there’s almost this perception that you’re a guy who can be DFA’d. Essentially, the next person who picks you up gets you for nothing, so you’re just as expendable to the next team because they got you free.”

Different strata make up 40-man rosters. Of the 25 players on any given major league team, there is the core with a safe roster spot, a group of prospects who needed to be added so other teams couldn’t poach them in the Rule 5 draft and then those, like Shaffer, considered expendable enough to be DFA candidates.

Considering his age (26) and his power (30 home runs among Double-A, Triple-A and the major leagues in 2015) and his versatility (he can play first, third and outfield), Shaffer never judged himself among the latter group. He figured his future in Tampa Bay might be over, as the Rays were loath to commit major league plate appearances to him last season, but 1,160 other roster spots existed around the game, and surely he’d warrant one.

Then Seattle designated Shaffer on Dec. 7. A few weeks earlier, the Mariners had lit the fuse on a truly absurd circle by DFA’ing pitcher David Rollins, who over the next month was claimed and DFA’d by the Chicago Cubs, Texas Rangers, Phillies, Rangers again and Cubs again before clearing waivers and staying with the Cubs but not on their 40-man. Shaffer’s voyage was just beginning, and he’d learn a valuable lesson that night, as he tried to mask his misery.

Danielle’s office was throwing a Christmas party. And rather than explain what DFA means and what the 40-man roster is and send her co-workers scurrying to the bar to escape the baseball nerdiness, she had a suggestion for her husband: Just pretend you’re still with Seattle.

“For five hours,” Shaffer said, “ had to tell people how pumped I was to be with a team I was no longer with.”

Over the next week, Shaffer hung in DFA limbo, baseball’s closest thing to purgatory. During it, teams can negotiate with the team that designated the player on a trade. If none materializes, the player is placed on waivers, and teams are offered a chance to grab him for free, with the worst record from the same league getting the first crack all the way through the best team in the opposite league.

Rebuilding Philadelphia plucked Shaffer from the scrap heap, and he was excited. The Phillies were young. They wanted to build a winning culture. Surely they’d love having a guy who, when given the silent treatment by Rays teammates after his first major league home run, broke into one of the greatest celebrations ever, high-fiving the air and giving a bro hug to a cloud of oxygen.

Six days later, Philadelphia DFA’d Shaffer.

“Then I got picked up by Cincinnati and thought, man, that’s an even better spot,” Shaffer said. “Philly had Maikel Franco at third. Cincinnati had Eugenio Suarez there, but he wasn’t a true third baseman. So I was like, this might be my shot to actually play third.”

A month later, Cincinnati DFA’d Shafer.

The Indians claimed him immediately, and Shaffer got the same call he’d been getting all winter, from a team official welcoming him to the organization.

“When you claim a guy, it’s an easy call to make,” Indians general manager Mike Chernoff said. “Making the call on the other side is a lot more challenging. Every offseason you have to do it with a few guys. In season you have to do it a few times. We just want to be honest with them and tell them what the situation is.”

The Indians’ situation, it turned out, wasn’t good: Four days later, they traded for reliever Carlos Frias and DFA’d Shaffer. His pain was simply keen strategy for Cleveland: Since the Indians were near the bottom of the teams capable of claiming him, they were banking on him clearing waivers and staying in their organization, just not on the 40-man. He did.

And here he is now in Indians camp, leading the team with four home runs as well as 21 strikeouts in 55 at-bats. It may not be enough for him to make the team, even with the injury to second baseman Jason Kipnis possibly warranting a move of third baseman Jose Ramirez to second, opening up the possibility of Shaffer getting at-bats there.

Why not? The Indians would need to create a 40-man spot for him.

“Even though all that stuff happened, I have a uniform,” Shaffer said. “I get to go out there and play. If I have an opportunity to show them what I can do, that’s all I need. It’ll be a cool story to tell when I’m giving some awards speech. You might say it’s business, but you made the incorrect business decision.”

Despite its best efforts, this winter didn’t crush Shaffer’s spirit. It fortified him. It told him that if he needs to go to Triple-A, that’ll be fine, so long as down the road teams won’t see him as damaged goods. Just look at Jose Bautista. He was taken by the Baltimore Orioles from the Pittsburgh Pirates in the Rule 5 draft 13 years ago and bounced to Tampa Bay, Kansas City, and the New York Mets before heading back to Pittsburgh.

These are the stories worth remembering, and far enough removed from it, Shaffer can chuckle at his own. While Danielle returned most of the stuff she ordered for their families, Shaffer did keep one piece: a customized sweatshirt with his last name on the back.

“It’ll be a memento for the offseason,” he said, hopeful there’s not another one like it, that he no longer has to do the limbo, that he can focus on RBI and OPS and any three-letter acronym besides you know what.