The hypocrisy of Tony La Russa and the understandable fears of black baseball players

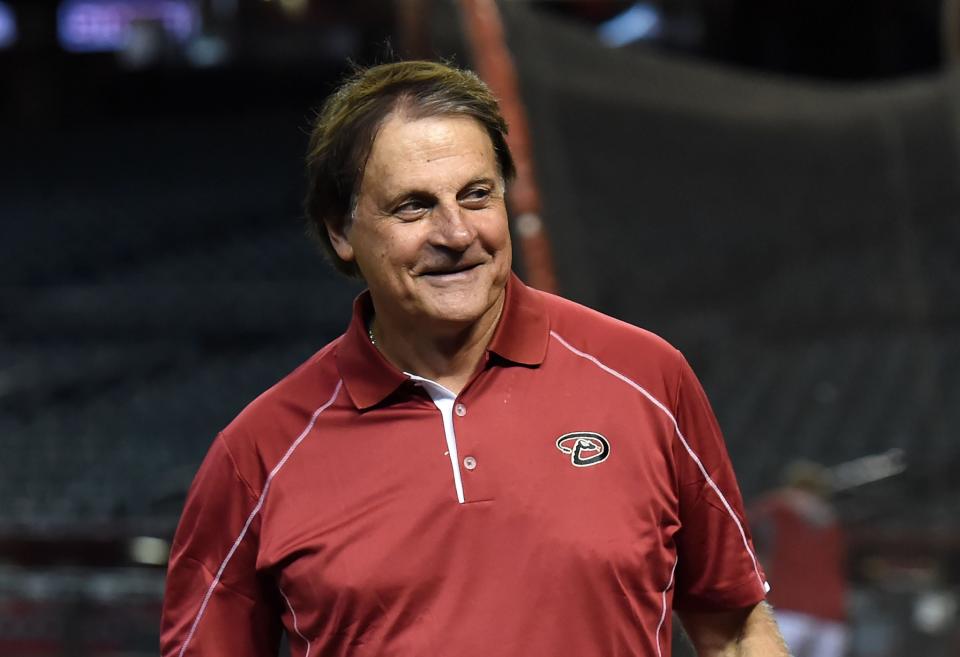

Tony La Russa, a convicted drunk driver who managed one of the most steroid-addled clubhouses in modern baseball history and today oversees an organization that at the trade deadline passed along to multiple organizations private medical information about a player it wanted to deal, spent Wednesday playing moralist, a role that suits him about as well as chief baseball officer for a major league franchise.

The impetus behind La Russa’s barrage of illogic was Baltimore Orioles outfielder Adam Jones, who called baseball a “white man’s sport” when asked why no ballplayer had emulated the protests of San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Were La Russa not so fundamentally myopic, he may well have realized he is exactly the white man of whom Jones speaks. And the worst kind at that: an authoritarian happy to share his opinion but not respectful enough to allow others to use their platforms in the same fashion.

“I would tell [a player protesting the anthem to] sit inside the clubhouse,” La Russa told “The Dan LeBatard Show.” “You’re not going to be out there representing our team and our organization by disrespecting the flag. No, sir, I would not allow it. … If you want to make your statement you make it in the clubhouse, but not out there, you’re not going to show it that way publicly and disrespectfully.”

Never mind that La Russa said this on a national radio program. Or that he essentially repeated the same during an interview on Sports Illustrated’s web site, in which he questioned Kaepernick’s sincerity and accused him of dishonoring the American flag. Because, no, Tony La Russa wouldn’t dare make something about himself in a public and disrespectful manner. That would be wrong.

Baseball is a complicated place for black men. The ones in front offices seldom apex to full decision-making power. The ones on coaching staffs rarely rise to the manager’s office. And the ones in uniform see that, and see their dwindling numbers on the field, and they talk about it among themselves, just how few faces look like theirs, how sometimes there isn’t a single person in whom they can confide the experience of being a black man in America, which, like it or not, is different and is tangible. Inside the Arizona Diamondbacks clubhouse La Russa put together, Rickie Weeks is the lone African-American, one of 25. And this is not rare.

So black ballplayers do talk with each other and they do wonder: Why is this the case? They don’t want to believe the sport they love is fundamentally racist, that there is some conspiracy against black ballplayers, but they know the number: 8 percent. Less than one of every dozen major league players is black. That’s more than half the number of a quarter-century ago, about a third of baseball at its peak. Even if baseball hasn’t actively sought to keep blacks out of the game, it sat around while the demographics changed and did nothing to plug the leak.

And now it’s left with a truth that African-American ballplayers for years have said among themselves and Jones elucidated publicly: Baseball, in America, is a white, elitist sport. Look at the crowds in stadiums. Look at the demographics of TV viewers. Look at youth tournaments. Whites overwhelmingly populate every corner of American baseball. And when Jones says he feels like there are two strikes against him, well, he understands men like Tony La Russa are waiting to turn a protest into a referendum.

“When he says it’s a white, like, elitist kind of sport, I mean how much wronger can he be?” La Russa told LeBatard. “We have tried so hard, MLB, to expand the black athletes’ opportunity. We want the black athletes to pick not basketball or football, but want them to play baseball – they should play baseball. And we’re working to make that happen in the inner cities.”

La Russa said it’s going to change because Major League Baseball wants it to change, and for someone who worked at MLB, he is awfully sanguine about the matter. Nearly every top executive in the commissioner’s office, whose job it is to grow the game, are frightened to death about baseball’s demographics and lose sleep at night trying to figure out how to recapture an audience it long ago lost. If La Russa wanted to help baseball, his best argument wouldn’t be that the sport is doing everything it can. This goes beyond trying hard. It’s about listening to someone like Adam Jones rather than demonizing him, listening to black youth who think baseball is boring. It takes hard work and harder conversations.

Instead, La Russa retreats into his bubble, which mistakes the place of Kaepernick’s protest with the intent. The point is not to disrespect the flag or the military because of his grievances. It’s to use the symbols of America to spur conversation and discussion that helps push the country toward a better place. Kaepernick deserves baseball’s gratitude. Because without him, the likelihood of Adam Jones speaking out on the matter is minimal. And if someone like Jones – a five-time All-Star and universally respected, thoughtful person – is too afraid to talk, what does that say about the environment that surrounds him?

It says he doesn’t want his message to be misappropriated by agenda-driven zealots who turn it into something it isn’t like La Russa did Wednesday. Never has Kaepernick been arrested, as La Russa was for DUI. Nor has he been linked to PEDs, as La Russa’s famous Oakland A’s clubhouses were. And while Kaepernick’s words haven’t torn asunder the 49ers’ locker room, the fact that a Diamondbacks executive shared the details of a player’s personal medical issue with other teams – and that the player and some teammates later learned of this and were appalled at the carelessness – only contributed to the toxicity that has permeated Arizona’s clubhouse all season.

It was rich, then, to hear La Russa demonize Colin Kaepernick, the person.

“I really distrust Kaepernick’s sincerity,” La Russa told LeBatard. “I was there in the Bay Area when he first was a star, a real star. I never once saw him do anything but promote himself.”

Maybe that’s because La Russa never looked. Kaepernick was adopted as a newborn after his parents lost two infant boys to heart disease. To honor his parents, Kaepernick asked them to find a charity to which he could donate part of his first NFL paycheck. They found Camp Taylor, a program for children with heart issues. Kaepernick’s involvement with Camp Taylor didn’t end with a check. He continues to devote time and money to this day.

It’s kind of like what La Russa does for animal rights. All of this stemmed from a media tour he was doing for an animal-adoption website, a great cause, too. In fact, if someone wanted to write a story about it, here’s a perfect headline:

FAILED BASEBALL EXECUTIVE WHO RAN FRANCHISE

INTO TOILET THROUGH BAD TRADES, SIGNINGS AND DRAFTS

TRIES TO REDEEM SELF WITH GOOD DEEDS FOR CREATURES

This is how Tony La Russa wants you to see Colin Kaepernick and Adam Jones and everyone else who crosses the threshold he and those of his ilk long ago marked: Their words, their actions, are inextricably linked with, and even a result of, their failures. It’s one of the oldest tricks, like blaming poverty on the impoverished, and it only reinforces the power structures onto which men like La Russa cling.

La Russa’s defensiveness Wednesday was that of a man threatened. His invocation of patriotism and reverence for the flag was nothing more than a canard. True patriotism is the recognition of speech, however uncomfortable it may be, and real reverence of the stars and stripes is the understanding that it is a symbol of that very freedom.

Perhaps between now and the end of the season, a Diamondbacks player will choose to exercise that freedom and, in the process, show La Russa as someone whose bark is bigger than his bite or whose stubbornness will make him look even worse. Either way, Tony La Russa’s words on Wednesday were plenty: full of hypocrisy and hubris and privilege, everything Adam Jones talked about fearing, and rightfully so.