A World Cup expanded to 48 teams is a bad, no-good, awful idea

Have you ever tried to get toothpaste back into the tube?

It’s super hard. And for all kinds of reasons to do with physics and chemistry – probably, we at FC Yahoo weren’t very good at science in high school – it can’t be done practically. Expanding soccer tournaments is sort of the same thing, along the same principles as our home-baked pop science.

Make a tournament bigger and it’ll never again be smaller. The toothpaste will never be successfully reinserted into the packaging from whence it came. Because once it’s out, there are too many forces keeping it there, and it’s too hard to get it back in.

Oh, you’re still with us after that tortured metaphor?

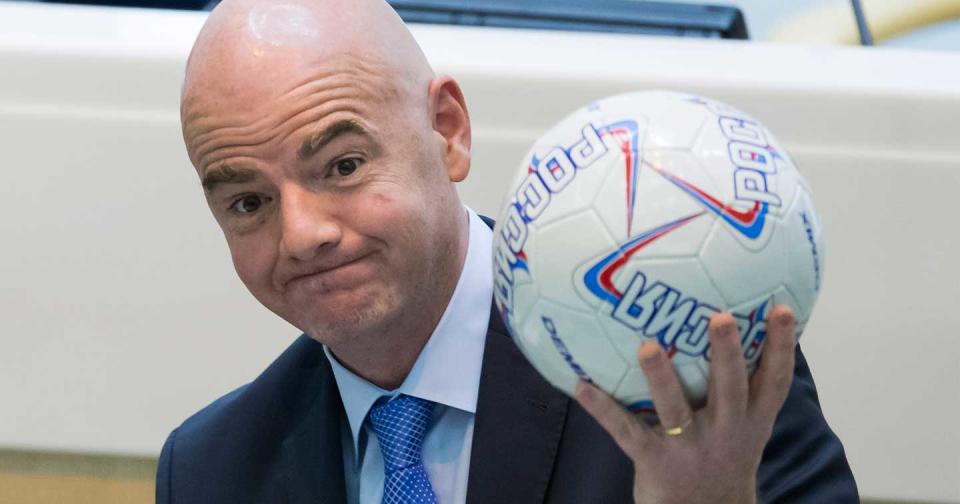

Good. Because the point is this: new, expansionist FIFA president Gianni Infantino is now making noises of expanding the World Cup, a perfectly good 32-team tournament, not just to 40 teams, as he had suggested during his campaign, but 48. This is bad for all manner of reasons.

Chiefly, it’s bad because if he manages to push this reform through, it’s pretty much irreversible. The World Cup has gone from 13 teams in 1930 to 16 thereafter (except for 1938, when Austria’s political Anschluss with Germany also unified their teams; FIFA decided not to name a replacement and stay at 15 teams). Then, in 1982, it became 24 teams. In 1998, the tournament expanded to its present size, 32.

The European Championships went from four teams in 1960, to eight in 1980, to 16 in 1996, and – unhappily – 24 this year. This latest bloating was rather a bust as the Euro didn’t really gurgle into a full churn until the knockout rounds. It took several weeks and more than two-thirds of the games just to knock out a third of the field. Predictably, it made for some languid affairs.

Still, soccer only ever gets bigger, save for a pre-World War II one-off. Because bigger tournaments means more revenue. And it means more happy federations. Which means more votes for whoever promises expansion and then delivers it. There are far more incentives for soccercrats to expand than to shrink.

Even if the product is better in small tournaments. Even if it concentrates talent and makes the games better and the viewer – the ultimate customer – happier on the whole. There is no precedent of contraction, other than perhaps the wise move to ax the brief second group stage in the UEFA Champions League, a round of 16 drawn out into six more games that rendered the tournament such a slog that it was killing the product and promised rebellion among the clubs.

Under Infantino’s new World Cup plan, 16 teams would qualify directly and another 32 would compete in a de-facto play-in game for a spot in the group stage. Which is to say that the tournament would grow from 64 games to 80 and 16 teams would be sent home after a single match. Then the tournament would progress as it exists in its current format. “More countries and regions all over the world would be happy,” Infantino declared before laying out all the avenues for added revenue. So there we have it once more: money and happy voters.

He apparently ditched the plan for 40 teams because it would make the formatting awkward – which didn’t stop the Euro.

Certainly, such a 48-team format would improve the chances of the United States hosting another World Cup, as it hopes to in 2026, when the changes would take effect if the FIFA Council – the successor to the Executive Committee – approves the plan in the coming months. How many countries could host that many games in a short span of time without spending themselves into a crippling recession, after all?

Yet there is no concrete evidence or logic to suggest that a tournament of that size would serve the consumer. There are barely 32 teams in the world worthy of playing at the existing World Cup. It wasn’t so terribly long ago that several entrants would get routed every four years. This suggests, on the one hand, that expansionism does eventually succeed in increasing the number of countries who can compete on the world stage. But on the other, it could make for some ugly walkovers in the early editions.

With almost a quarter of every national team in the world qualifying, there is no safeguarding the quality of the play. There was a reason the Euro was, until its latest edition, a more competitive tournament than the World Cup. There was a relatively smaller concentration of soccer powers in the tournament, with the fat trimmed from the juiciest, choicest cuts of meat. Expansion means diluting and weakening.

Meanwhile, the World Cup qualifying mechanism, which keeps international soccer firmly in the spotlight for the two years up to the big tournament, would be undercut significantly. They are a financial boon to the regional confederations, and they create a framework for program- and team-building that culminates, for 32 select teams, with the big tournament at the end of the road. If the size of the World Cup did indeed swell by 50 percent, it would presumably mean just about every one of the six teams in CONCACAF’s final hexagonal round – due to kick off next month, as it happens – would qualify. The same would be true elsewhere. The entire notion of qualifiers would became largely uninteresting with a spot in the tournament devalued into a participation medal of sorts.

Little drama would remain until the World Cup itself, when the phalanx of teams and bevy of games in the play-in round would create logistical migraines for the hosts and an overabundance for the viewer.

As for the USA, such a format could well mean that if it isn’t among the 16 highest-ranked teams worldwide, it wouldn’t be seeded – unless seeds were divvied up regionally, rather than in one big global pool. The Americans aren’t often in the global top 16. That could routinely subject the Yanks to the vagaries of a one-off elimination game, a format in which they haven’t had good luck at the World Cup, going 1-4 all time.

While the political upside to Infantino and his fellow power brokers is large, the downside for the sport itself is enormous. Expanding to 48 teams is reckless because there’s plenty of reason to believe it might not be a success. And yet once it’s implemented, there will be no reversing it on account of the countries it would put at increased risk of missing out on the newly diminished number of places at the sport’s premier event.

Because of the physics of soccer governance.

Leander Schaerlaeckens is a soccer columnist for Yahoo Sports. Follow him on Twitter @LeanderAlphabet.