NBA owed 3 ABA Pacers $35K a year. Two lived to see it happen. One died fighting for it

INDIANAPOLIS -- A point guard, center and power forward played with a red-white-and-blue basketball. They blazed a trail on a shiny hardwood court in a fast-paced league with flashy moves, halftime shenanigans and players made of true grit.

The point guard was Freddie Lewis. The center was Mel Daniels. And the power forward/center was Bob Netolicky.

All three men gave their might, their talent and their careers to the American Basketball Association, most of their seasons with the Indiana Pacers. The ABA lasted nine years. The three gave nearly 27 combined years to the ABA.

When it was over, Lewis became a coach and school teacher in Washington, D.C. Netolicky worked 25 years in the auto auction industry. And Daniels was a coach and NBA front office advisor.

None of the three made millions in basketball. Not even hundreds of thousands. But all three were promised pensions when the NBA merged with the ABA in 1976, absorbing four of its teams.

The pensions didn't come right away. Years passed. Then decades. The clock kept ticking and all three men, as they waited for the money, were vocal advocates, pushing the NBA for the pensions.

When the NBA voted in June to give recognition payments to 115 former ABA players -- nearly 50 years after the leagues merged -- Lewis and Netolicky were there to see it. Daniels, the fiercest ABA player advocate for the pensions, died in 2015, still doing everything he could to get his "brothers of the ABA" money.

This is their story, one of big dreams and superstars left behind. This is their story of fighting for the money they say they deserved.

"I'll take it with a grain of salt," Lewis, 79, told IndyStar of the money promised from the NBA. "They could have done a whole lot more for the guys, but they chose to do it this way. You know, we as players coming from the old league, we never made that kind of money that they're making today, so anything helps us.

"We are just in a position where there is nothing we can do about it, but accept it."

'It doesn't set well'

Lewis was one of the greatest to play in the ABA, a lightning quick point guard who could read the court, arguably, as well as any pro player before him.

In a buzzer-beating second, he could pull back from 18 feet, with two or three opponents in his face and drain the shot for a playoff win. He paved the way for legendary NBA point guards who came after him.

But Lewis came first.

He was so highly sought after that he is the only player to start his career in the NBA, play all nine seasons in the ABA and sign back with the NBA when the two leagues merged in 1976.

He won three ABA championships with the Pacers. He was a four-time ABA All-Star, with the Pacers, and also played with the Spirits of St. Louis and the NBA's Cincinnati Royals. He averaged 16.6 points, 4.1 assists and 4.0 rebounds in seven seasons.

And yet, after playing 11 years in two professional basketball leagues, Lewis lives just like most people live.

His 94-year-old mother, Thelma, had a stroke a few years back that left her unable to walk. Lewis is her only child. He moved from his home in Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C., to care for her.

"She needs 24-hour, 24-7 attention," Lewis said. "We don't know how much time. I try to take her where she needs to be and try to keep her comfortable."

Basketball seems a lifetime ago for Lewis. His days now are spent as caregiver, chauffeur, financial planner and son. But sometimes, when his mom brings it up or when a memory flashes through his mind, Lewis remembers those days.

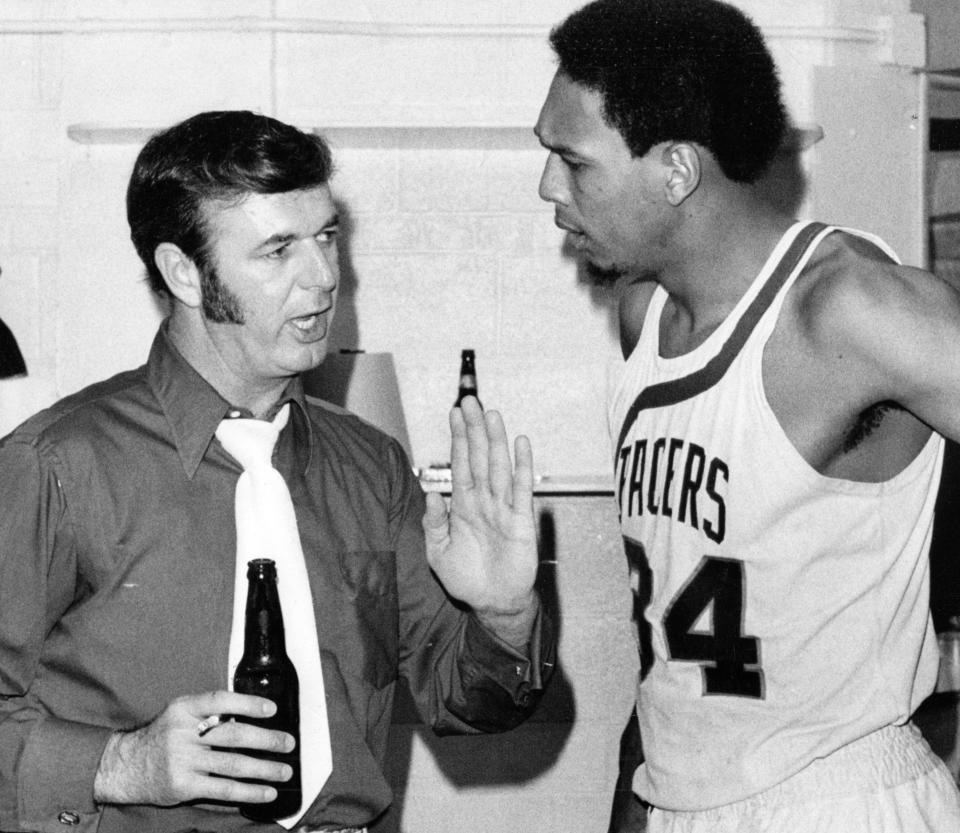

"He was our steadiest performer and leader in the playoffs," Pacers coach Bobby "Slick" Leonard once said of Lewis. "He plays good defense. He does almost everything well. You can't let him shoot. And he'll drive on you. There's really no way to stop him."

Lewis was a player at a time when athletic greatness in the pro ranks didn't equal big money, not the multimillion-dollar contracts of today. And that was OK with Lewis at the time, because he just loved to play. But now, it isn't OK with Lewis and it hasn't been for decades.

Looking back on his basketball career, Lewis has felt financially slighted. He always thought, at the very least, he should have been given a pension from the NBA for his years of service to a league that is now a multi-billion-dollar enterprise.

The NBA board of governors voted in June to give $25 million to former ABA players, still living, as recognition payments for their years of service in the league. Players eligible either spent three or more years in the ABA or played at least three combined years in the ABA and NBA and never received a vested pension from the NBA.

The agreement pays players an average $3,828 annually for each year they were in the league. For example, a player with the minimum three seasons will receive $11,484 a year. A player with the most years of service, such as Lewis, will get $35,452 a year.

Lewis came out on top, but it's still not enough, at least in his calculations.

"It's just time. They should have did this thing years ago. The NBA, I just can’t imagine why they wouldn’t give the ABA a pension. They're calling this 'recognition' to keep from giving us a pension," he said. "I have 11 years in and they're only giving me (money) for nine so they are taking two away with this type of plan.

"It doesn't set well, but, everything helps. And we are thanking the Lord every day for the time we have here."

And that the NBA agreed to pay something to former ABA players while he was still alive to see it.

'This is like a godsend to us'

Netolicky turned 80 on Tuesday. He lives in Texas, is a grandfather and is poised to get the highest payment possible from the NBA, $35,000 a year.

"It's better than nothing," Netolicky told IndyStar from Texas this week. "They gave that one kid at Minnesota $62 million, but they're giving us a couple grand. They should just give us a million for each year we played. That would be just fine."

The kid at Minnesota is Karl-Anthony Towns who last month agreed to a four-year, $224 million supermax extension with the Timberwolves, his agent, Jessica Holtz of CAA Basketball told ESPN's Adrian Wojnarowski.

Four years. $224 million. Netolicky shakes his head at that and laughs. He played in the ABA nine years, with Indiana, Dallas, San Antonio, then back to Indiana. He retired with the Pacers at the start of his ninth season.

An All-American at Drake University, Netolicky was on the 1967-68 ABA All-Rookie Team, a member of the 1969-70 ABA All-Pro Team, a 4-time ABA All-Star and played on two Pacers ABA championship teams.

Netolicky was the "smoothest shooting big man in the ABA" with a "quick release (and) excellent eye," Jim O'Brien wrote in his "1972-73 Complete Handbook of Pro Basketball. His "best move (was) juke toward baseline and cut for the foul line for a fine, floating jump shot. ... Unstoppable hook shot going to his right . . . Looks like choirboy, but hits offensive boards like a demon."

Netolicky retired from the ABA in 1976 with career averages of 16.0 points, 8.9 rebounds and 1.4 assists. He averaged nearly 50% shooting in 618 games.

In 1978, Netolicky joined the Baltimore Metros/Mohawk Valley Thunderbirds of the Continental Basketball Association and played eight games, averaging 15.0 points and 7.0 rebounds. The team was coached by Lewis. Netolicky then had a chance to play in the NBA with Cleveland and coach Bill Fitch.

"But I had just got engaged, had a house in Indianapolis," Netolicky said. "And back then, you're not talking about these millions of dollars. You're talking about enough to buy a car."

When he returned to Indy, Netolicky worked a stint in real estate, then went to Florida to coach for a year with the CBA's Sarasota Stingers at the same time Phil Jackson was coaching at Albany. Netolicky said it's crazy to think he coached against Jackson and what different paths their lives took after that.

Netolicky worked for 25 years in the auto auction business. "Then I kind of got old and just kind of semi-retired," he said. "You're semi-retired as long as you're walking, right?"

The money. That recognition payment he will get from the NBA "is like a godsend to us," he said.

"I'll put it this way. I didn't make a fortune, you know. Fortunately, I've saved a few bucks and I'm not worrying about my meal everyday, but I'm basically breaking even," he said. "This will give me what's called a little security about taxes going up. I don't have to worry about extra expenses and things like that."

Netolicky knows plenty of former teammates who do have to worry about their next meal. When the ABA disbanded in 1976, merging with the NBA, four of its 11 teams were absorbed by the NBA — the Pacers, Nuggets, New York Nets and San Antonio Spurs. Many players were left with no pension, salaries shut off and health insurance gone.

"Every one of the guys, we were promised a pension. We were promised things and it fell through the cracks," Netolicky said. "I'm not going to mention names, but I know some guys living on social security, just making ends meet and this is going to let you go to sleep at night and you're not going to have to worry."

While Netolicky, like Lewis, believes the NBA should be paying former ABA players more, he knows that is out of his control.

"It was 50 years ago and it wouldn't do any good to scream and yell about it now," he said. "And they're, the NBA is doing the right thing for everybody. There are going to be guys this is really going to help."

Beyond the money, Netolicky said is the recognition finally for what he and his former teammates did on the court. Until now, he felt like a superstar left behind.

"The money is wonderful, but it means that they are recognizing what we did, that we actually were pioneers," he said. "Instead of just somebody out there that nobody knows."

'Such a big voice in all of this'

Daniels had this crazy idea nearly 10 years ago. Really it wasn't so crazy, he said, when the billion-dollar dynasty called the NBA was his target. Daniels wanted the NBA to help his former teammates of the ABA.

He had visited New Orleans and found former ABA players living under bridges. He saw players all over the country struggling financially, unable to pay medical bills, pay rent and even buy groceries.

Daniels and Indianapolis attorney Scott Tarter, along with eye doctor John Abrams and filmmaker Ted Green got together and started the Dropping Dimes Foundation, a non-profit to help struggling former ABA players and their families. The foundation's No. 1 goal was to get the NBA to pay pensions to living ABA players.

Months before Daniels died in 2015, he helped former player Charlie Jordan pick out a new suit with Dropping Dimes, and he told IndyStar how sad it was to see his league- and teammates suffer.

"They don't have anything," Daniels said. "People don't know how bad off they are."

Daniels was an outspoken advocate as Dropping Dimes fought for pensions. He died never getting to see the NBA acknowledge what the league's players had done for the modern game.

"I think of Mel and how much this meant to him," said Abrams, who is the Pacers' team eye doctor. "He was such a big voice in all of this."

Daniels didn't need the money, at least not like many of the 115 players.

His career in the ABA was illustrious, playing for the Minnesota Muskies, Pacers and Memphis Sounds and with the NBA's New York Nets. Daniels was a two-time ABA Most Valuable Player, three-time ABA champion and a seven-time ABA All-Star. He was the all-time ABA rebounding leader, and in 1997 was a unanimous selection to the ABA All-Time Team. Daniels was enshrined into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 2012.

He averaged 19.4 points and 16.0 rebounds during his six years in a Pacers uniform. At his first practice with the team, Daniels was shooting jump shots from 15 feet. Coach Leonard walked up and issued a warning. “Next time you shoot from that far out,’ Leonard said, “I’m gonna punch you in the nose.”

“And that was that,” Daniels said in 2014.

After retiring from basketball, Daniels remained a fixture with the Pacers, even when the team moved to the NBA. In 1984, Daniels was an assistant coach and later became an executive on the basketball side as the team’s director of personnel.

At Daniels' funeral, ABA legends talked about his remarkable talent on the court, but most talked about his loyalty to the ABA off the court, including his fight for money from the NBA.

“He was always there for you,” Lewis told IndyStar when Daniels died in 2015. “He stood up for me and anybody else."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: ABA Pension: Freddie Lewis and Bob Netolicky on what NBA payments mean