Nationals and Yankees throw 2020's first pitch, but the story remains far from the field

WASHINGTON — If everyone would just grit their teeth, keep their eye on the ball and not the empty seats, baseball would finally get to focus on baseball again. That was the plan, anyway. They played swelling music and raised a World Series championship flag in our nation’s capital Thursday, a heavy-handed metaphor about the political expedience of pretending that everything is just fine.

But even from a seat in the press box — one of just a few dozen people who would witness the 2020 opening day live — I barely noticed.

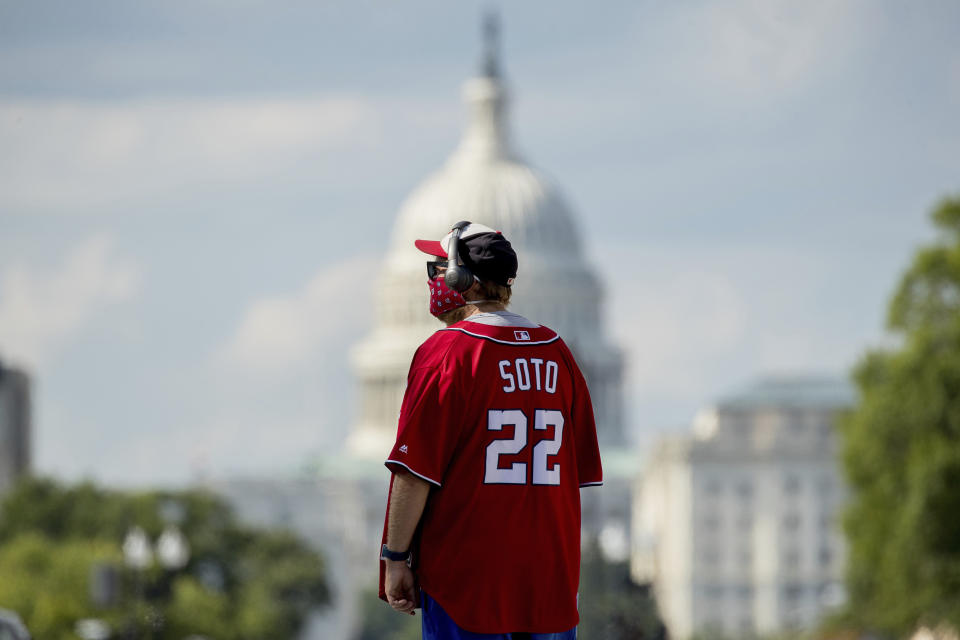

Without the context clues from a celebratory crowd, the whole thing felt like a dress rehearsal. The PA system seemed insufficiently calibrated for an empty stadium, every sound echoing incoherently. Even the message of Black Lives Matter, which deserves to be made loud and clear, felt muddled by finding a middle ground. Everyone knelt in unison before the anthem started. No one knelt during the anthem itself.

Then they played some baseball — not a full nine innings, mind you. Torrential downpours forced a suspension in the top of the sixth and after a two-hour rain delay, the grating music was turned off and a scoreboard announcement flatly indicated that the game was over, gone out with a whimper. The New York Yankees won, 4-1, and by the end even the disembodied fans who populate the uncanny soundtrack had gone home.

A more hackneyed writer would ham-fist an analogy about how the heavens decided baseball shouldn’t come back yet. But if you were looking for a sign, you could have found it on the front page of a newspaper, where rising COVID-19 numbers are printed.

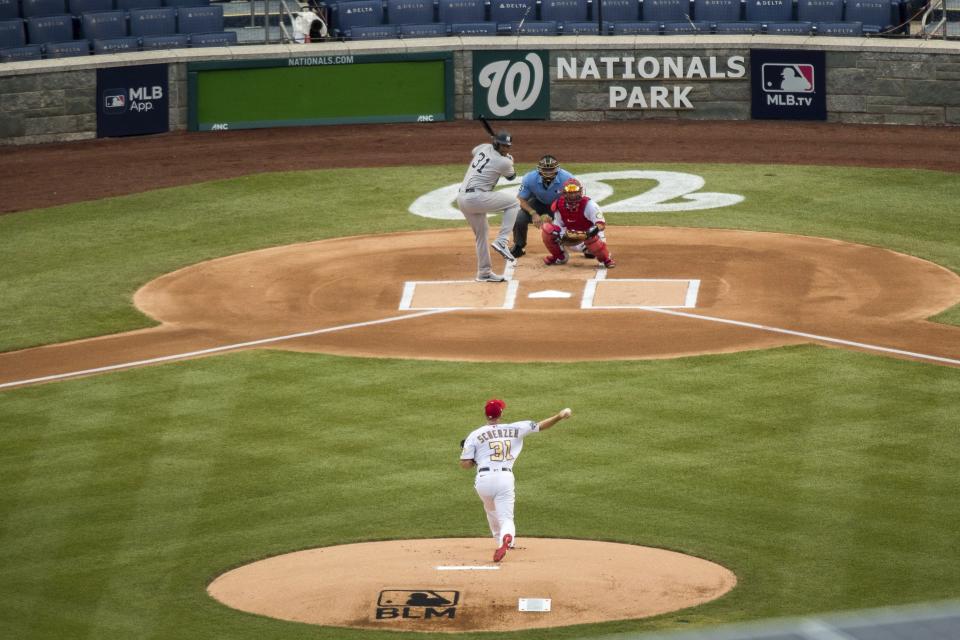

Or in the fact that Juan Soto, the dynamic outfielder for the reigning champs, tested positive for COVID-19. The results came hours before the Washington Nationals were supposed to usher in the season with a showdown between their ace Max Scherzer and Fall Classic nemesis Gerrit Cole, now starring for the Yankees.

It was not the first positive test in the league, nor will it be the last. But it represented a devastating blow to the Nationals, to fans of exuberance within the game, and to the festive optimism of opening day. It is also, potentially, the source of an outbreak. Unless it’s just a false positive. Knowing the difference is critical to the competitive integrity of MLB’s season and the safety of everyone involved. And now, it’s not even clear what we know.

Here’s how the timeline went, as far as it can be pieced together: On Monday, Soto practiced with his team, on the open half of MLB’s every-other-day testing schedule for monitoring players in-season. On Tuesday, he was tested upon arrival to the stadium. Then he practiced with his team and scrimmaged against the Orioles. He didn’t play in a mask, which is permitted and seems to (understandably) be the widely preferred option. There are photos of him not wearing a mask in the dugout, which is also permissible.

MLB’s official guidelines advise teams to have inactive players make use of auxiliary seating to allow for increased social distancing within the dugout. Players are told to limit unnecessary movement and discouraged from leaning on the railings. Frankly, even noticing his dugout behavior feels like scapegoating Soto for the fact that there’s baseball being played in a pandemic and he’s following the letter of the law laid out for him by his employer. But it’s potentially relevant.

On Wednesday, Soto worked out with his team at the stadium. Early Thursday morning, medical staff notified Nats brass that Soto’s Tuesday test came back positive. According to GM Mike Rizzo, it was the only one of the Nationals tests from Tuesday that was positive. The question, then, is whether Soto, as an asymptomatic carrier, inadvertently infected anyone else on his team or the Orioles between his last negative test (administered Sunday, results on Tuesday) and finding out he was positive Thursday.

Before the game, Rizzo said that the team was “casting a wide net,” but that “at this point there's nobody else that is ineligible because of the contact tracing.” A statement issued by the team reaffirmed that “none of our players or staff were deemed to have met the CDC definition of close contact.”

That definition hinges on spending at least 15 minutes within six feet of an affected person “or being in direct contact with secretions from a sick person with COVID-19 (e.g., being coughed on).” Under MLB’s guidelines, both Soto and anyone who was determined to have had close contact with him would face increased scrutiny and undergo expedited diagnostic testing.

Reportedly, Soto himself underwent several rapid tests that all came back negative. If no one came in close contact with him, no other rapid diagnostic testing would be necessary. But, reportedly, other players were subject to rapid testing as well.

The team declined to confirm or deny that Soto had tested negative on follow-up tests, though reliever Sean Doolittle alluded to the team “hoping that it was a false positive” in his postgame press conference. It’s not clear whether anyone else had undergone rapid testing Thursday in addition to the normal, scheduled diagnostic tests that will yield results in 24-48 hours.

They can dress it up in pinstripes and old ballplayer cliches, but the story this season is always going to be what’s happening off the field. It’s a distraction if the point is baseball, or else it’s proof that baseball isn’t a sufficient distraction when the stakes are so high.

It’s disingenuous to say that just because a single positive test shut down sports back in March that the league’s response — or lack thereof — to Soto’s infection (or Freddie Freeman’s, or Aroldis Chapman’s) necessarily indicates a callous disregard for the safety of players. We know more about the coronavirus than we did five months ago — the effectiveness of masks, the likelihood of transmission via surface versus aerosol.

And although the fields have been fallow, baseball hasn’t been idle all these months. The league, in conjunction with the players association, was working on how to resume play safely. Maybe it’s foolish that they believed it would be sufficient, but it’s not naive to say that they believed it. This wasn’t ever intended to be a death cult. They’re not sending guys out there unarmed. The protocols are designed to keep the rest of the team safe even if someone in their midst is sick. The testing is designed to stop the spread before it gets out of hand.

In that sense, a single player testing positive — even before the very first game, and even the confusing chain of questions that will inevitably follow — is an expected cost of doing business this year.

But to say it was inauspicious would be an understatement.

More from Yahoo Sports: