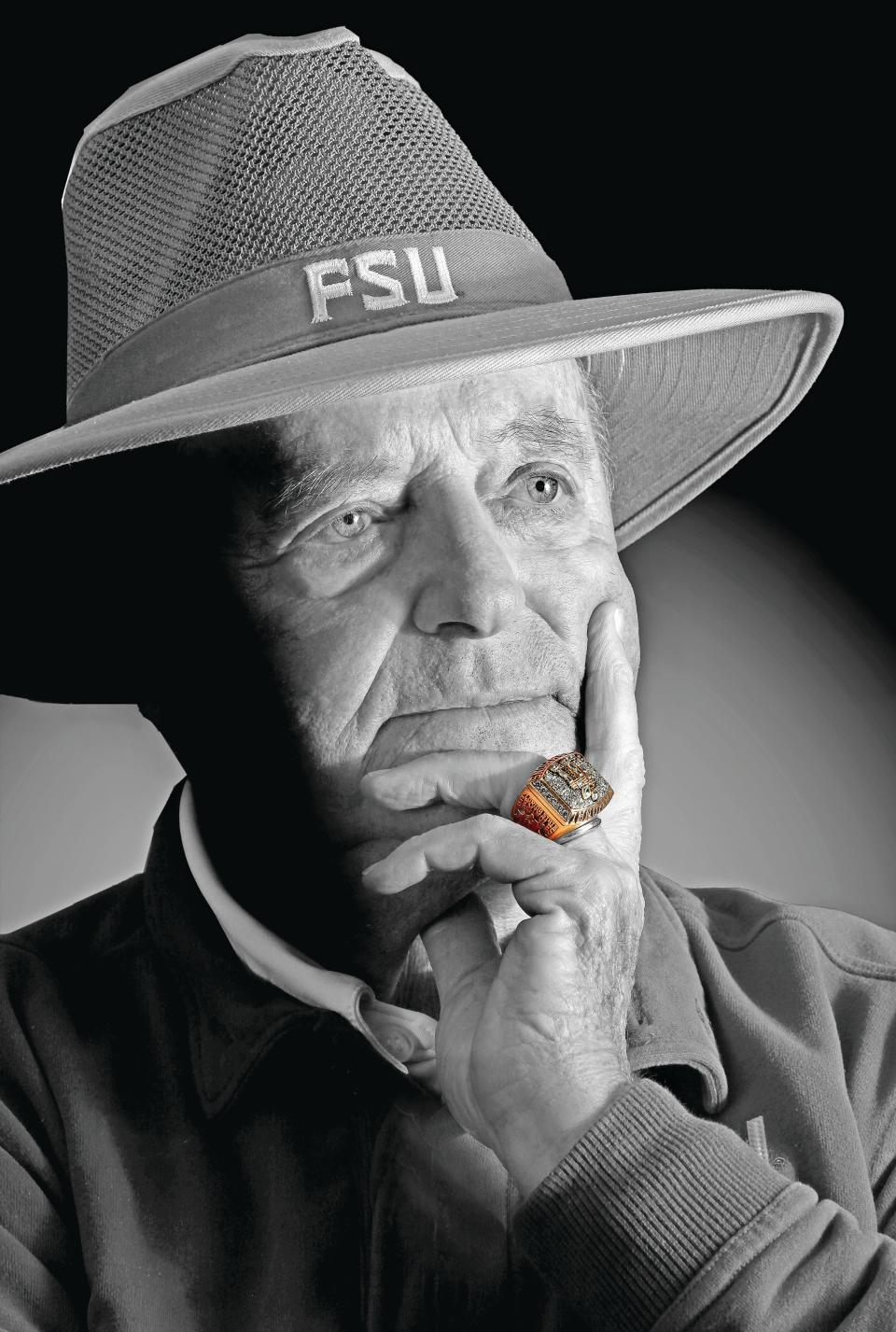

His name shall endure: Bobby Bowden took FSU from 'nowhereland to splendor' | Gerald Ensley

EDITOR'S NOTE: Years before Tallahassee Democrat reporter Gerald Ensley passed away in 2018, the longtime reporter and columnist penned this previously unpublished news obituary and tribute to legendary Coach Bobby Bowden, who died early Sunday morning. As the community mourns his passing, we share it here.

There may be more to life than football.

But Bobby Bowden made it king at Florida State, where he created football history as coach of one of the nation’s top programs.

Now history has claimed Bowden, who died weeks after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Mourning a garnet and gold giant:

Legendary coach built Florida State into college football powerhouse

Early to bed, early to rise. Morning calls with Coach Bowden and Ann were special | Jim Henry

Here are the 10 most important games in the Bobby Bowden era at FSU | Skip Foster

Bobby Bowden to lie in honor at Florida Capitol; Public service set for Tucker Civic Center

Photos: Former FSU coach Bobby Bowden through the years

He was surrounded by his family — wife, Ann, and their six children — when he passed away at 5:08 a.m. at his Killearn Estates home, daughter Ginger Bowden told the Democrat Sunday morning.

"He passed peacefully," Ginger said. "His family was with him during the night."

Bowden was 91.

As it says in Bowden’s favorite book, the Bible: His name shall endure forever.

Bowden coached Florida State from 1976 through 2009 — and took FSU football from "nowhereland to splendor," as longtime Tallahassee Democrat sports editor Bill McGrotha once termed it. Taking over a program just three years removed from an embarrassing, winless 0-11 season, Bowden fashioned a college football dynasty.

Words from Donald Trump: Former President extends well wishes to Bobby Bowden

Mike Norvell's address to the ACC: Florida State head coach pays tribute to Bobby Bowden

Lost art:FSU's Bobby Bowden, staff often relied on letters to communicate with players

Over his 34 years as FSU head coach — a span longer than all seven previous FSU coaches combined — Bowden posted a 316-97-4 record. He won two national championships, took FSU to 30 bowl games and led the Seminoles to an NCAA record streak of 14 consecutive years (1987-2000) in which they won at least 10 games and were ranked among the nation’s top five teams each season.

He retired with an overall coaching record of 377-129-4 at three universities — ranking him the second-winningest major college football coach in history.

Bowden was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2006, having already been named to the Florida Sports Hall of Fame (1983).

Bowden achieved fame on the football field as an offensive magician, who made no-huddle and shotgun formations, reverses and trick plays a staple of the FSU attack. He assembled a loyal and brilliant staff, and was the charismatic force in recruiting the nation’s top players from Miami to California.

More: Tributes from coaches, players to 'legend among legends' Bobby Bowden pour in

More: On social media, fans look back with love, respect to Bobby Bowden

Bowden won admiration off the field for a humble, humorous personality unlike almost any football coach in history. He dazzled the media with his candor and self-deprecating jokes. He endeared himself to the public with his Southern charm and religious devotion.

He won the affection of his players with his loyalty and penchant for giving erring players second and third chances.

Bowden’s success, combined with his religious faith and common man appeal, earned him the nickname of St. Bobby.

"The one question everybody asks me: Is Bowden the same way you see him on TV? I’m very proud to say he is the same person," linebacker Darryl Bush said in 1999. "He has a great sense of humor and represents things that are good. There is nothing phony about him."

Bowden was FSU's savior from West Virginia

Few would have predicted such success in 1976.

Bowden was a seemingly undistinguished former FSU assistant coach enjoying only mild success as the head coach of West Virginia. FSU was only three years removed from the 0-11, Chicken Wire scandal season of 1973. FSU fans clamored for a local favorite, like former coach Bill Peterson or Leon High legend Gene Cox – and insisted the program need a savior.

In Bowden, they got the savior.

His first season brought only five victories — but that was nearly double the total of FSU’s two previous seasons. His second year produced a bowl game — and more importantly, FSU’s first victory over arch-rival Florida in nine years.

By his fourth season, Bowden had taken FSU to an undefeated regular season and its first visit to a major bowl game (Orange Bowl). By his fifth season, FSU claimed its first-ever Top 5 finish (5th) in the season-ending college football poll.

Bowden became a household name. He was dubbed the Riverboat Gambler, because of his penchant for trick plays, such as a game-winning "puntrooski" against Clemson in 1988 — which sports pundit Beano Cook called "the greatest play since My Fair Lady."

He was called King of the Road, for his success in beating big-name teams in their own stadiums, particularly during 1981’s Octoberfest, when FSU reeled off-road victories against Notre Dame, Ohio State and LSU.

Bowden became the subject of documentary films (1986’s "Finding A Way" and 2017's THE BOWDEN DYNASTY: A Story of Faith, Family & Football), a half-dozen books (including 1992’s best-selling "St. Bobby and The Barbarians") and innumerable television, magazine and newspaper stories. He even appeared in a sitcom, "Evening Shade," starring FSU alum Burt Reynolds.

More: 'A TRUE SEMINOLE': Bobby Bowden and others remember Burt Reynolds, a Tallahassee legend

Florida State's dynasty years under Bobby Bowden

For 14 consecutive seasons, from 1987 through 2000, FSU won at least 10 games and finished among the nation’s top five teams — both of which were NCAA records. In that span, the Seminoles won 13 of 14 bowl games and claimed two national championships (1993, 1999 ).

Bowden’s overall college coaching mark of 377 victories was second only to Penn State’s Joe Paterno (394 victories). Bowden was one of only 10 coaches at any college level to have amassed 300 coaching victories.

The secret was Bowden's personality, as FSU Dean of Social Work and longtime athletic board member, Coyle Moore, acknowledged soon after Bowden arrived.

"He speaks our language, adheres to our religious faith and fits our needs like a glove," Moore said.

Bowden often agreed with that assessment. Over the years, he turned down entreaties to coach at Wisconsin, Baylor, LSU, Wake Forest, Marshall, Auburn and even fabled Alabama, pronouncing himself content to make his stand in Tallahassee.

"Northwest Florida has my kind of people — whatever kind it is, it is my people," he said. "I was born right up yonder (in Alabama), and I live right over yonder (in Tallahassee)."

Sickness, faith and football

Robert Cleckler Bowden was the second of two children born to Bob and Sunset Cleckler Bowden in Birmingham, Alabama. Bob was a bank teller, who later operated his own construction company; Sunset was a housewife. Bowden, born Nov. 8, 1929, was 18 months younger than his sister, Marian.

"My father was uninhibited. If he wanted to sing, he sang. If he wanted to laugh, he laughed," Bowden said. "He laughed a lot. I got that from him."

Bowden was a mischievous boy, remembered by childhood pals for such pranks as sneaking into theaters, throwing rocks at streetlights and playing basketball naked with a group of friends in a deserted high school gym.

He also was an athletic and talented lad. He played high school baseball, basketball and football. He spent summers as part of a trick diving team, which entertained at Birmingham pools. He played trombone in the school band and a jazz ensemble.

At 17, he became enamored of a pretty 14-year-old brunette who lived two blocks away and attended his church: Ann Estock. Two years later, following his freshman year of college, they eloped to Rising Fawn, Ga., where they were married on April Fool’s Day, 1949. They had to borrow a car, got stopped for a speeding ticket that took all their cash and waited more than a week before telling their parents. The marriage endured for the next 72 years.

The most pivotal year of Bowden’s childhood came when he was 13 and stricken with rheumatic fever, an inflammation of the lining of the heart. An old family practitioner predicted that unless Bowden avoided strenuous exercise, he would not live to see his 40th birthday.

Bowden was forced to drop out of school and spend six months lying in bed. He credited his recovery to the twin themes that would dominate the rest of his life: religion and football.

Throughout his illness, the congregation of the church the Bowden family attended, Ruhama Baptist Church, prayed for Bobby’s recovery. Their dedication and his eventual recovery "increased my belief in God," Bowden said.

During his illness, Bowden also became an ardent fan of the Woodlawn High football team, which practiced right across the street from his home. He kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about the team.

After a second doctor assured his parents that exercise would not hurt his heart, Bowden joined the Woodlawn team in 10th grade, becoming a star halfback and passer. Though only 5-foot-8 and 160 pounds, he was a fast runner and had a budding coach’s understanding of the game.

"He had a good football mind even then," recalled high school teammate John Lee Armstrong.

Bowden was recruited to Alabama by the legendary Bear Bryant, where he found himself one of 13 quarterbacks. Eager to play — and newly married, a condition Bryant didn’t allow his players — Bowden transferred to Howard College back home in Birmingham. At Howard, Bowden became a Little College All-American quarterback.

At Howard, Bowden also got his first glimpse of FSU: He quarterbacked the Bulldogs to a 20-6 loss to FSU in the 1950 game that dedicated FSU’s Doak Campbell Stadium. Fifty-four years later (2004), the stadium was renamed Bobby Bowden Field at Doak Campbell Stadium. A stained glass portrait of Bowden was added to one end of the stadium, overlooking a bronze statue of Bowden.

Still, Bowden always wondered what might have been.

"I wouldn’t trade my experiences at Howard for anything," he once said. "But I’ve always regretted leaving Alabama. I’ve wondered what it would have been like to play at that level."

Instead, he learned what it was like to coach at that level. He spent a couple of seasons as a graduate assistant coach at Howard, then spent four years as head coach of South Georgia Junior College. In 1959, Howard brought him home as head coach.

At Howard (now Samford University), Bowden mounted a 31-6 record that remains the best winning percentage (.838) in school history. He then joined Bill Peterson’s staff at FSU for three years, and coached receivers, such as future NFL Hall of Famer Fred Biletnikoff and future FSU president T.K. Wetherell, during FSU’s first foray on the national scene.

He went to West Virginia as an assistant coach in 1966, then succeeded head coach Jim Carlen in 1970 and led the Mountaineers to a pair of Peach Bowl victories before returning to FSU in 1976.

The rest was history.

"What I admire is (Bowden’s) ability to do it year after year," Steve Spurrier, coach of rival Florida, said upon the occasion of Bowden’s 300th victory in 1999. "Anybody who has lasted as long as he has, has to be doing things the right way."

Bowden was a favorite among reporters

Bowden’s way had big dollops of humor, candor, religious devotion and human frailty.

Bowden was quick with a quip, and fast to find the humor in every situation — sometimes through the tears. After yet another loss to Miami had cost FSU yet another shot at the national title, Bowden joked "On my tombstone it will say: But he played Miami."

Bowden’s love affair with the media was legendary. Where other coaches avoided the press or muttered platitudes, Bowden embraced every chance to talk with reporters and prided himself on saying something interesting to every interviewer.

More: Ever wonder how Bobby Bowden became a football coach? New podcast reveals this and more

He let reporters in the locker room during halftime talks, wore television microphones during big games and rarely encountered a question that he felt deserved "no comment."

He disarmed critics with such frank postgame admissions as "We out-slopped the world today." He filled up reporter notebooks with quips, such as “If short hair and good manners won football games, Army and Navy would play for the national championship every year.”

The result was even the most hardened reporters adored Bowden, and not coincidentally he received almost uniformly "good press."

"We’re in the selling business. We need the press," he said. "I don’t agree with everything they write. But a guy walks in here, and I nearly feel like I owe him a story."

Bowden’s open attitude wilted a bit in the early 2000s, following a spate of stories and criticism that struck close to home. In 2003, his oldest son, Steve, was sentenced to six months of home detention for his role in a $10 million investment fraud, in which one of the investors was his father. In 2006, his youngest son, Jeff, resigned in the face of mounting criticism after seven seasons as FSU offensive coordinator.

For a brief period after Steve’s conviction, Bowden stopped talking to the media and closed the FSU locker room after games. Even after he resumed talking to the media, he was curt with reporters he felt were unfair to him, and he was rumored to be behind the firing of FSU radio commentator and former FSU quarterback Peter Tom Willis, who had described the Jeff Bowden-led offense as a “high school offense.”

“I think the (media) profession has gotten a bit out of line,” Bowden said of his new attitude toward the media.

Bowden particularly opposed Jeff’s resignation, which he believed had been forced by the media, who he said, “were listening to eBay, email and all that junk.” He reportedly ponied up a portion of Jeff’s severance package of $537,000 over five years.

‘‘It’s just amazing,’’ Bobby Bowden said. ‘‘When things go wrong the first thing they blame is the offensive coordinator. That’s kind of the game we Americans play.’’

“I am disappointed in Jeff’s decision,” continued Bowden, whose team was 5-5 and was coming off a 30-0 home defeat to Wake Forest at the time of the resignation. “This is a big loss for me personally. His decision is an emotional one for me.”

He was a private man, but everyone was Bobby Bowden's 'Buddy'

Bowden called everyone "Buddy" because he was terrible with names, even those of his players whose names he routinely mispronounced on his radio and television shows. Indeed, he had a little-advertised penchant for malapropisms and incorrect word choices — “(Notre Dame) comes in with an unblurred record,” — that sometimes left reporters scratching their heads.

Yet Bowden had a superb and uncanny memory for every football game he ever coached or watched, recalling pivotal plays and subtle mistakes decades later.

“It was probably because I was so into the games,” he said.

Bowden was a man of few vices. He claimed to have never tasted alcohol. He chewed but never smoked cigars. He had a well-publicized weakness for all things chocolate, but worked hard at keeping his weight down, especially after his cholesterol began to rise in the 1990s.

His only real weakness was Red Man chewing tobacco, which he did only out of range of his wife.

"It’s my way of being bad," he joked of chewing tobacco.

For all his openness in public, Bowden was zealously private off duty. He refused invitations to dinner parties, was reluctant to go out to restaurants and — despite the dozens of products he endorsed — rarely went shopping. He was notorious for disappearing into his den when guests came to the house. He had hundreds of acquaintances but few close friends.

He had two hobbies: military history and golf. He read voraciously about World War II, and during his later years visited numerous battlefields in Europe. In 2015, he hosted a documentary series, “Bobby Bowden Goes To War,” that was filmed over several visits to Normandy.

“I was raised during World War II. So I became very interested in the military,” Bowden said. “A lot of those skills and strategies carry over (to football). Some things that General Patton and Stonewall Jackson said, I can use. You’d be amazed how much the strategy of (war and football) are alike.”

Bowden adored golf — playing to a 10 handicap — and lived in Tallahassee in a house off the seventh fairway at Killearn Country Club. He wouldn’t play from August to February when football or recruiting were in full swing.

But he made up for it in the spring, by playing in near daily tournaments as he visited Seminole Booster clubs around the state, and in the summer when he played frequently with his sons. Into his late 80s, he played at least nine holes at Killearn four or five days a week.

God and family, then football

Bowden often said his priorities were God, family and football. And God clearly occupied a major part of his life.

As a young man, he pondered a career in the clergy, but said he abandoned the idea because he felt he "never got the call." But he remained a devout Baptist who embraced every chance to speak to church and youth groups, visiting as many as 150 churches of all denominations ever year.

"I’m not an authority on anything," Bowden said. "But I can talk football pretty good. And I can talk about what Christ means to me, and they can take it for what it’s worth."

Bowden’s religious beliefs were often stricter than many expected, given his easy going personality. He spoke out strongly against premarital sex, and for years refused to hire any coach who was divorced (softening that stance after three of his sons were divorced). But that was the religion he grew up on.

"Bobby is a literalist," said his wife, Ann. "If the Bible says the whale swallowed Jonah, then Bobby believed the whale swallowed Jonah. It was not a metaphor to him. But he set a great moral example for the children.”

Despite a deep love of family, Bowden was never quite Ward Cleaver around the house.

He and Ann had six children in 10 years, and he left most of the raising and disciplining to Ann, who sometimes complained, "Bobby always wants to be the good guy." Bowden did become notably closer to his four sons when they became adults, and all became involved in the family business of football.

Steve ran the Bowden football camps. Tommy, Terry and Jeff all became coaches — with Tommy leading Çlemson against FSU in the first father-son coaching matchups in NCAA Division I-A history (1999-2007, with Bowden winning five of the nine games).

But even then, he liked visiting with children and grandchildren "only up to a point," said Ann. "He doesn’t want to look like he’s interfering in their lives."

Bobby and Ann were a sometimes tumultuous pairing.

She was outspoken and ambitious, and not afraid to chide her husband over his aversion to material gain and self-promotion. She wowed reporters with her insight and candor, and was the source of most stories about Bowden’s distaste for socializing and houseguests. He responded with tolerance and humor.

She was often the principal figure in his booster tour speeches, as he joked about her spending habits and her out-sized devotion to her children — often accusing her of rooting for her coaching sons to beat him when they coached at other schools.

More: FSU's Bobby and Ann Bowden celebrate 70 years of marriage

But their affection for each other never wavered. She regularly marveled at his generosity and equanimity when criticized. He praised her insights and drew upon her advice before any big decision. Both spoke frequently of being "partners."

"All my success is because of Ann’s drive," he said. "She’s been the inspiration and discipline behind my success."

His beliefs in the importance of religion and family found their greatest flower in his forgiving attitude toward players who made off-field mistakes. Arrested players were often suspended, but allowed to return to the team after serving their legal and/or team punishments.

During FSU’s dynastic run, particularly, Bowden endured criticism from the national media for such tolerance. Critics charged that Bowden was too lenient and that FSU was an "outlaw" program because of it.

Bowden was not above dismissing players, such as future NFL star Randy Moss and Bryne Malone, following repeated or serious legal violations. But many more erring players, from Mike Shumann to Sebastian Janikowski to Peter Warrick, were disciplined then returned to the team.

In a 2001 Esquire interview, Bowden repeated a familiar refrain: “I believe in second chances.” In a 2000 interview on “60 Minutes,” he explained leniency was part of his commitment to the parents of players.

“That mama knows I’m going to try to treat her son like mine,” Bowden told Charlie Rose. “They can look at my history. History says Bobby Bowden will discipline your child but he won’t kick them out on the street unless he has to.

“The way I look at the public is they get excited like they were in the Coliseum in the first century and the second century. Kill the Christian, kill the Christian. People love a hanging but I don’t want people hanging my players. Punish ‘em and give ‘em another chance.

“Coaches who do not change with the times ain’t here no more. Thirty years ago, I’d kick ‘em off at the drop of a hat.”

Bowden also believed in giving enemies a second chance. Spurrier was a constant thorn, but you could never get Bowden to criticize him. His philosophy (explained in Esquire) was “If somebody mistreats you, treat ‘em good. That kills ‘em.”

More: Column: Saint Bobby is the ultimate class act. A salute from Steve Spurrier

What was Bobby Bowden's first-year salary?

Coaching before the era of $6 million annual coaching salaries, Bowden did not become wealthy from football.

His first-year salary at FSU was $37,500, and the figure was steadily nudged upward until he was making more than $2 million when he retired, plus thousands more in endorsements.

Yet Bowden cared little about money and material goods. At West Virginia, he turned down a free partnership in a Taco Bell franchise as too much trouble, and he refused the gift of a speedboat because he didn’t have room for it in the garage.

He also proved not the most savvy investor. In 1983, he pulled out of a Louisiana land investment group when its development project became controversial, missing out on a $700,000 payday when a district court eventually ruled in favor of the investors. In the early 1990s, he was dunned for a reported six-figure penalty to the IRS, after a series of ill-considered investments by a former financial advisor.

In 2000, he lost $1.6 million when he and 13 other investors were bilked by a phony investment fund, for which he was recruited by his oldest son, Steve — who avoided prison time in part because his father spoke up for him after Steve pleaded guilty to selling unregistered securities. In 2010, he flirted with bankruptcy because of money spent on unsuccessful condominium investments urged on him by his sons, Terry and Steve.

“There is no way any of my children would (purposely) scam or swindle me,” Bowden told a judge. “Steve still manages my money. I have not lost one bit of confidence or trust in him whatsoever.”

After retirement 'one big event left'

Bowden was not eager to retire, even as he reached his 80th birthday in 2009.

“When you retire,” he quipped, “there’s only one big event left.”

But by 2009, his final season, the FSU program was in a downward spiral. Three times over Bowden’s last five seasons, FSU finished a single game above .500, and twice had to win bowl games to finish with 7-6 records. FSU ranked only once among the nation’s top 25 teams in those five seasons – and that was 21st.

FSU attendance was dropping and Boosters were clamoring for a change in coaches. Bowden wanted to coach at least one more year.

“What alumni don’t realize is this: They say ‘I went to school there. That’s my alma mater. Dadgummit, I don’t like what’s happening there,’ “ Bowden said. “Well, they were here for four years. I’ve been here 34 years. They don’t realize I love the school, too.”

![Dec. 14, 2009: In his office at Doak Campbell Stadium Florida State University head football coach Bobby Bowden reflects on aspects of his long career coaching the Seminoles. Bowden had just recently announced he was soon to retire. [Jon M. Fletcher, Florida Times-Union]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/GUpH9J4w9qnhGouOJikIcg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTQ3OA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/tallahassee-democrat/75d9bd350496f8750383636a2fd7b43e)

More: From Hughes to Bowden to Norvell, a historical look at Florida State's head football coaches

But Bowden’s successor was already in place. In 2007, LSU offensive coordinator Jimbo Fisher was hired to replace Jeff Bowden, and the following year he was designated FSU’s head coach-in-waiting by President T.K. Wetherell.

And after the 2009 season, Wetherell, who had already announced his own resignation, felt it was time to pull the trigger.

“It was tough. It wasn’t fun but I had to do it,” Wetherell said in 2013. “I couldn’t leave this for the next president, whoever that was going to be.”

The decision rent a gulf between the former wide receiver and his position coach, and they didn’t talk for five years. Finally, FSU alumni director Scott Atwell, with help from Bowden’s former administrative assistant, Sue Hall, brokered a meeting. The two men met and talked for 15 minutes at the 2014 Homecoming breakfast. Though neither discussed what was said, they shared several big smiles and shook hands warmly upon parting.

“Bobby wasn’t interested in it being publicized,” Atwell said. “But I felt it was something we needed do as university. Both of them are strong Christian men who didn’t need to pass away without meeting face to face.”

“Bobby was never bitter. He was hurt,” Hall said. “He told me he always thought the school and the boosters would take care of him. But that’s not what happened. It was touching to hear what was said (between Bowden and Wetherell). It went very well. ”

Bowden continued to live in Tallahassee after his retirement, and his relationship with FSU eventually grew warm again.

In 2012, Bowden was named to the FSU Athletic Hall of Fame, joining several dozen of his former players.

In 2013, Bowden attended his first FSU game since retirement, as the university saluted Bowden and his 1993 national championship team with a ceremony at halftime – with Bowden earning a sustained standing ovation from the crowd. In 2015, FSU honored Bowden on the field during a game to commemorate the 35th anniversary of his being named the Bobby Dodd National Coach of the Year.

In 2013, Bowden also signed a deal for $250,000 a year (plus half the net royalties from any merchandise created using his image) to promote FSU for Seminole Boosters. The boosters dropped the contract after two years but continued to hire Bowden for individual events for several years.

In 2017, the feature-length documentary “THE BOWDEN DYNASTY: A Story of Faith, Family & Football” was released in 400 theaters nationally for a one-night live premier. Bowden said his dream was for the film to be placed in every school and church in the country.

Bowden remained active late into his life, playing golf and traveling to either share his testimony in churches and at FCA meetings, or giving motivational speeches to civic and business groups. His final testimonial was at a Tampa Bay-area church in mid-September.

Bowden also returned to FSU at least twice to speak to the football team – in 2017 for coach Willie Taggart and 2020 for coach Mike Norvell prior to the Seminoles' season-opener against Georgia Tech.

Back story:

Florida State head coach Mike Norvell pays tribute to Bobby Bowden at ACC Football Kickoff

Legendary Bobby Bowden enjoys meeting with Florida State football coach Mike Norvell

Bowden was awarded with the inaugural Florida Medal of Freedom by Gov. Ron DeSantis in April 2021. The Medal of Freedom acknowledges an individual who has made a worthy contribution to the citizens of Florida and the public endeavor.

Bowden was also a well-known supporter of former President Donald Trump.

He introduced Trump at a rally in Tampa in 2016. And Trump was among the large number of people that wished Bowden well on social media after Bowden announced to the Democrat in July that he had a terminal medical condition.

The coach's final days in Killearn Estates

Bowden was slowed by lingering, painful back and hip issues that kept him off the golf course and from walking his neighborhood during his later years.

The coronavirus pandemic that forced the country into a shutdown in March 2020 also kept Bowden and Ann close to their Killearn Estates home for months. The couple wore protective masks and practiced social distancing when away from home.

Bowden was hospitalized at Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare in mid-September for nearly 10 days for a leg infection after he had skin cancer spots removed. He was transferred to the hospital’s rehab facility and released on Thursday, Oct. 1.

Two days later, on Oct. 3, Bowden was informed by his physician that he had tested positive for COVID-19 – the infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus.

Bowden's health started to decline after the diagnosis.

After his recovery and almost two weeks in the hospital, Bowden was hospitalized again in late June for five days for fatigue and additional medical tests.

On July 21, Bowden and his family announced to the Democrat that Bowden had been diagnosed with a terminal medical condition. A day later, his son Terry – the head football coach at Louisiana-Monroe – told the media his father was battling pancreatic cancer.

As the end neared, Bowden was surrounded by family and loved ones.

When previously asked by journalists how he wanted to be remembered, Bowden, who would have turned 92 in November, said:

"That I served God’s purpose for my life ... I've had writers ask me what I want my legacy to be, it’s not anything to do with football, I want it to be that he served God’s purpose with his life. And I hope I have. I haven’t done as good as I should, but I’ve tried."

Jim Henry updated this report.

No one covers the ‘Noles like the Tallahassee Democrat. Subscribe now so you never miss a moment.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Bobby Bowden took Florida State from 'nowhereland to splendor'