Shrewd but cynical: MLB proposal corners richest stars as prey for richer owners

Months after the coronavirus pandemic first forced shutterings of retail and restaurants, cancellations of concerts and conferences, and the total nosedive of the economy, the financial hits keep coming. Across the country and across industries, workers are facing unemployment, furloughs, or reduced salaries. It’s a second Great Depression that’s sparing few below the billionaire threshold.

As an unavoidable measure, there are steps conscientious companies can take to mitigate the personal destitution of their employees if cuts have to be made. Namely, the people at the top can forgo a great portion of their salaries. A higher percentage of a bigger number will be more overall money and should keep more precariously positioned members of the labor force from bearing the brunt of any lost revenue.

By this logic, the proposal Major League Baseball delivered to the union on Tuesday looks reasonable, or at least humane. Rather than a rumored revenue sharing measure, the league is asking for economic concessions from players in the form of a sliding scale of pay cuts. Players due the most money (like Mike Trout at $37.7 million this year) will lose a greater percentage of their salary, players who make the minimum ($563,500) will forgo a much smaller percentage of their smaller salaries.

Potential salary cuts in MLB plan, sources tell @JesseRogersESPN and me:

Full-year Proposal

$563.5K $262K

$1M $434K

$2M $736K

$5M $1.64M

$10M $2.95M

$15M $4.05M

$20M $5.15M

$25M $6.05M

$30M $6.95M

$35M $7.84M— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) May 26, 2020

Frankly, it’s a shrewd move by the league. Avoiding the “non-starter” of revenue sharing while still making an opening ask for “massive” pay cuts. And, crucially, splitting the interests of the union’s many members along an uneven line.

According to the Associated Press, there are 44 players who were set to make more than $20 million in 2020. They are, in large part, the guys whose names you know. They’re also the ones who stand to lose the most money and might be willing to fight the hardest against such a proposal.

That same study found that 369 of the total 899 players who were on active rosters when they were frozen at the suspension of spring training in March have salaries of $600,000 or less. They’re the players who are less economically secure to begin with. They stand to lose less. They’re of the cohort whose earning potential is often sacrificed to the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the sake of the stars. There’s also a lot more of them.

With sports’ summer return seeming increasingly like a welcome inevitability to a population going stir-crazy and politicians prematurely touting games’ symbolic value as a harbinger of a “return to normalcy,” the players were always going to have a difficult public relations battle on the subject of their splashy salaries. A fan base facing historic unemployment numbers has proven to be largely unsympathetic to the plight of professional baseball players — no matter that their employers tend to be worth billions.

Now, the league has managed to spin the disingenuous rhetoric around whether millionaire athletes are inherently overpaid into an internal debate for the other side of the table to work out while the fate of the season hangs in the balance.

The best leverage the players ever have is refusing to take the field. With a COVID-19 vaccine many months away at a minimum and draconian set of precautions necessary to even start a season that may eventually encounter a second wave of the pandemic, veterans may well balk at a proposal that stands to pay them less than a quarter of their expected 2020 salaries. The issue is: Will the pre-arb players — whose total take-home numbers were always going to be significantly smaller, but who stand to make closer to half of their expected pay this season under the owners’ opening proposal — balk alongside them?

The MLBPA has historically prioritized maximizing high-end salaries and protecting veteran players. It has done so successfully — retaining baseball’s status as the only major American sports league without a salary cap staunchly, even now. But the players have paid in public perception, framed as greedy and ungrateful. The sliding scale proposed by the league is almost Machiavellian in the way it leverages that reputation to counteract the strength of those gains. And enlists the interests of lower-paid players — or at least the appearance of their interests — to do so.

The compensation system laid out in the CBA already subsidizes older stars by artificially suppressing the earning potential of young talent under team control. Players have a small window of opportunity to cash in on their prodigious ability and also be made whole for the years they played for far below their market value. Asking those higher-paid players to now subsidize the salaries of their lower-paid brethren is the owners taking advantage of a disparity they helped build — dividing the union and pulling from both ends.

Blake Snell’s comments about getting paid the money he earned were seen as self-serving before this proposal. Now top-tier players will be expected to sacrifice for the sake of patriotism and the pandemic and because some guy in the comment section said he’d play for free, and also because it’s only fair that they take a bigger pay cut considering everything that’s happening in the country.

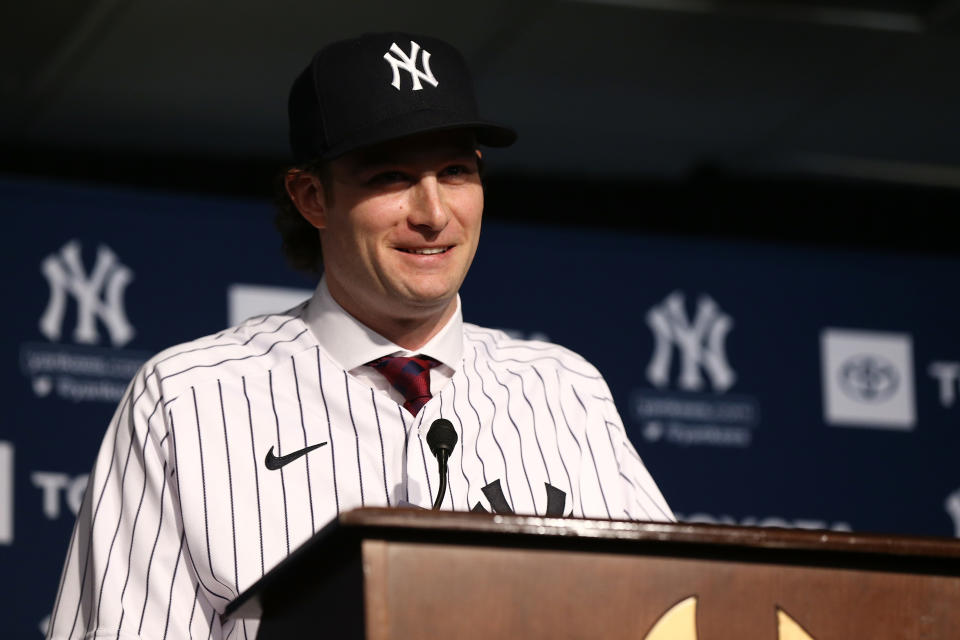

But here’s the thing: players already are taking a pay cut. In March, MLB and the union agreed to a series of proposals that addressed things like service time in the event of a canceled season and salaries if baseball could return. By that deal, players — all of ’em, from the rookies up through Gerrit Cole — would take roughly 50 percent pay cuts in an 82-game season.

Much of the acrimony that characterizes the current round of negotiations stems from a disagreement about whether that compensation can be cut again now that games will — at least at first — be played without fans. The sliding scale proposed on Tuesday ramps up the cuts to range from 53.5 percent for league-minimum earners to almost 78 percent for players making $35 million. Owners say it’s not economically feasible to pay their players even the prorated salaries without ballpark revenue, though they have thus far refused to prove that point substantively.

Times are tough and pulling from the top earners is the most ethical way to balance the books. Many team front offices and even the commissioner’s office have instituted pay cuts targeting their highest-paid employees. Rob Manfred and other top league executives, for example, are reportedly taking 35 percent pay cuts to ensure the job security of other employees in that office. But, despite how this proposal is structured, owners aren’t asking stars to give up three-quarters of their salary while playing during a pandemic for the sake of protecting the neediest baseball players. (They’ll screw those guys over just the same.) They’re just doing it to protect their own profits.

Hannah Keyser is a reporter at Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Email her at Hannah.Keyser@yahoosports.com or reach out on Twitter at @HannahRKeyser.

More from Yahoo Sports: