How Mexico is recruiting another kind of dual national: U.S.-born fans

It is one of the most iconic pilgrimages in American sports. The journey to the Rose Bowl begins on claustrophobic California freeways, then escapes, down into the picturesque San Gabriel Valley, the So-Cal sun likely still beaming high above the San Rafael Hills.

And if you had made the descent on a recent Monday afternoon, the last of May, you would have been blinded – not by that sun, but by green.

Green, everywhere.

Green flags fastened to cars, or draped over shoulders. Green replica jerseys and knockoffs, sombreros and masks. Massive banners adorning the stadium, heroes smiling down at you. And a 300,000-square-foot Futbol Fiesta, essentially a soccer theme park, outside. Thousands of fans of Mexico’s national team flocked to it on that Monday afternoon, and later to the famous venue itself, to get a real-life glimpse of those heroes in a friendly vs. Wales.

One of them was Sergio Tristan, a Texas-born lawyer and U.S. Army veteran, the son of two Mexican immigrants. He’s the founder, or El General, of Pancho Villa’s Army, the preeminent Mexican national team supporters group north of the border. And he’s one of millions who constitute the biggest and most passionate soccer fan base in the United States. It’s the one behind stateside TV ratings that often double and triple those for U.S. national team games. It’s the reason Mexico has played 45 matches on U.S. soil since the start of 2014, compared to just 14 back home. It’s the reason the average attendance at those matches has topped 55,000.

But Tristan also provides the Mexican Football Federation (FMF) with a window into untapped potential. He’s an example of why it’s evolving.

“I want to read about Mexican soccer,” Tristan says. “But it’s difficult for me to read in Spanish. So it’s very time-consuming. It’s not the best way for me to consume information.”

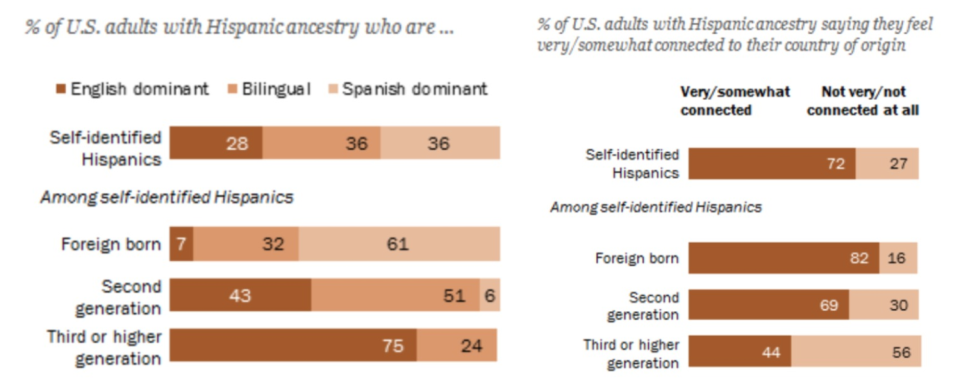

And he’s not alone. According to Pew Research Center data, 92 percent of second-generation U.S. Hispanics – the sons and daughters of immigrants – are either English-dominant or bilingual. Among the third generation and beyond, that number rises to 99 percent, with 76 percent primarily using English. And Mexican Americans mirror the overall Latino trend.

“A lot of second- and third-generation kids might speak Spanish, but they weren’t educated in Spanish,” Tristan explains, his words aligning with the statistics. “So they consume information in English.”

That’s why the FMF, as its general secretary Guillermo Cantu says, is “progressing into becoming a bilingual product.” Its commercial partner, Soccer United Marketing, conducted a study that found that 72 percent of the national team’s U.S.-based fans are U.S.-born.

“We are starting to speak not only in Spanish but also in English,” Cantu says. “We’re not only speaking to the Spanish-speaking fan, but the Mexican national team fan that is not necessarily Mexican-born. That is part of our target.”

The other type of dual national

It is not a war. Mexican national team director Dennis Te Kloese even shies away from the word battle. But the recruitment of Mexican American players by both the Mexican and United States soccer federations is the subject of increasing attention. For U.S. fans, after their program lost prized prospect Jonathan Gonzalez to El Tri, it’s also a subject of concern.

And it would seemingly be another area in which the aftershocks of the USMNT’s World Cup qualifying failure might be felt. The U.S. recruiting pitch presumably lost juice that night in Trinidad. Mexico’s, as a result, theoretically strengthened.

But Te Kloese refutes that idea. Conversations with dual nationals, he says, never arrive at senior national team success. Never, he says, has the U.S. failure been brought up. “It is more a family decision,” he says of the choice between the two programs, “than it is a technical decision.”

Joaquin Escoto, the director of Alianza de Futbol, mostly concurs. “They do bring up the youth system,” he says of Mexican scouts. “But not the World Cup.” So Trinidad hasn’t changed the landscape? “I don’t think so. No, no,” he concludes.

But even Te Kloese, who operates on the sporting side of the federation, knows there are opportunities for FMF in other departments – especially with the World Cup approaching, and with the American market, for the first time in 32 years, more or less to itself.

“The intention, or the idea within the federation, is to have a more international image,” he says. “And to expand.”

With over 36 million Mexican Americans living in the U.S., the focal point of that expansion is clear.

And the philosophy is starting to crystallize. In February, the FMF launched English-language Twitter and Facebook accounts that have been active and growing ever since. Its U.S. tour now has an English website, online shop and hashtag. It has 15 sponsors, which include some of the largest American brands.

Every stateside match now feels like a miniature Super Bowl. The Los Angeles sendoff wasn’t just a game; it was an entire long weekend that began with a Super Bowl-style media day. There was an English-language Men In Blazers event on Saturday, and open training on Sunday. On matchday, Mexican national team legends convened to sign pregame autographs for star-struck fans.

Many of those star-struck fans, of course, were kids. They’re the next generation of El Tri-loving Americans. And they’re the other type of dual national – the ones whom the Mexican federation knows it must lure.

Why English can ‘erase walls and frontiers’

Not only are there 36 million-plus Mexican Americans living in the United States; next year, there will be more. And the year after that? More still. Hispanics accounted for roughly half of the country’s total population growth from 2016 to 2017, according to Pew analysis. In 50 years, according to Pew projections, they’ll comprise nearly a quarter of the U.S. populace.

But not because they’re coming to the U.S. at higher rates than ever before. Crucially, immigration is slowing. In fact, nowadays, more Mexicans are leaving the U.S. than entering. Under a president who has openly antagonized Mexicans and promised to build a border wall, there is no reason to expect that trend to reverse.

Hispanic population growth, instead, is being driven by the later generations. By the sons of immigrants, people like Tristan, the ones who are learning and speaking in English, just like any other American-born child.

But they are no less Hispanic. Or, rather, most aren’t. Even among second-generation immigrants – only 8 percent of whom mainly speak Spanish – 69 percent say they feel very or somewhat connected to their country of origin, according to Pew research.

So there is clearly overlap. There are second- and third-generation Latinos who feel attached to two countries, or even three: the one(s) of their parents’ birth and their own. Whether U.S. Soccer and FMF know it or not, these are the kids they’re indirectly fighting over. These are the kids whose parents sing the Mexican national anthem with gusto, but whose wardrobe may include a fresh USMNT kit. The ones who feel pulled by Las Barras y Estrellas, but also El Tri.

And the vast majority of them are speaking English. Which is why the FMF must speak it back to them.

For years, it didn’t, and chances are it missed out on thousands of fans, just as U.S. Soccer did due to its own lack of Spanish-language outreach. The English-speaking, Mexico-supporting community was fueled largely by independent writers and bloggers who realized there was a market for what they could provide. Now, finally, the federation itself has caught on.

And in the USMNT’s World Cup absence, English-language coverage of the Mexican team has exploded. Several journalists will follow it to Russia to report for English-language outlets. Sports Illustrated and the Washington Post have run big features on it, with others soon to follow.

Cantu knows he and the federation still don’t communicate with fans in English nearly as well as they could. “We have a lot to learn,” he says. And frankly, even the social media accounts were long overdue.

But the strategy is in place. With the English-speaking share of the U.S. Mexican American population swelling, its importance is only going to grow. More action will come soon enough.

Because “what we are trying to do,” Cantu says, “is erase walls and frontiers.”

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell covers global soccer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.

More El Tri coverage from Yahoo Sports:

• 2018 World Cup preview hub

• Group F preview: Why everything depends on Mexico

• FC Yahoo Mixer: Why U.S. fans should root for El Tri

• Mexico team preview: Analysis, lineup projections and more